The Baltic Question | History Today - 5 minutes read

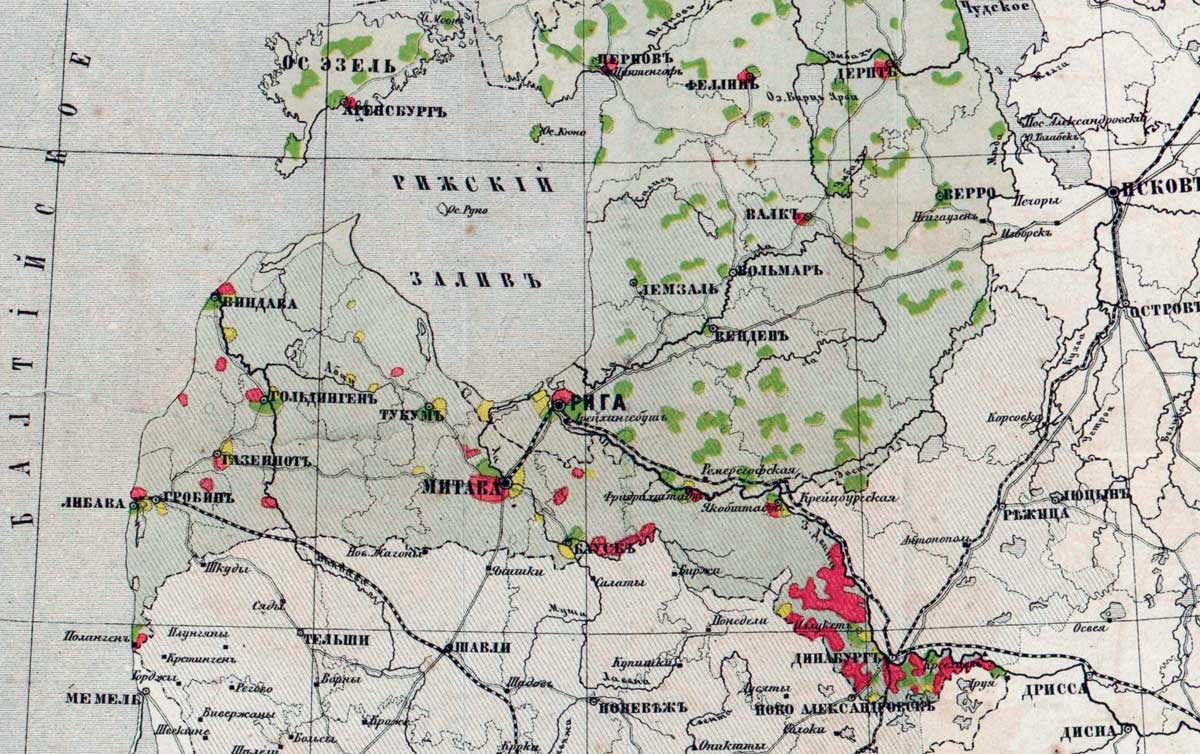

In 1873 Alexander Fedorovich Rittikh, one of the Russian Empire’s most eminent cartographers, published two maps of the Baltic provinces depicting the ethnographic and religious composition of the region’s inhabitants. Rittikh’s maps painted a vivid portrait of a multi-ethnic and confessionally diverse imperial borderlands. Yet, behind the veneer of scientific objectivity, the maps were also a politically motivated attempt to use cartography to legitimise Russian imperial rule over the region.

The three Baltic provinces of Estland, Livland and Kurland, which correspond to present-day Estonia and Latvia, had been incorporated into the Russian Empire over the 18th century. They continued, however, to be regarded as a distinct region within the empire, characterised by a degree of autonomy over local governance, special laws, German-speaking elites, Estonian- and Latvian-speaking peasantry, majority Lutheran faith and a manorial economy system. Over the course of the 19th century, the particularities of imperial rule in the Baltic, the ‘Baltic Question’, sparked debates among intellectuals about how to justify Russian imperial rule over non-Russian populations and the relationship between the empire and emerging ideas around a distinctive Russian national culture. One view held that the Baltic provinces were perceived by some as culturally part of ‘the West’ and used to present Russia as a truly European empire. Conversely, the ethnolinguistic and religious diversity of the borderlands was perceived by others as an extension of ‘the West’ into Russia’s borders and a potential threat to the development of Russia’s unique national culture.

Rittikh was firmly in the latter camp. The son of a doctor from Riga, he had distanced himself from his Baltic ancestry. Over the course of his military career he assimilated into Russian culture, abandoned the German spelling of his name (Rittich) and became a strong supporter of Panslavism.

The publication of Rittikh’s maps was funded by the Imperial Russian Geographical Society in St Petersburg, established in 1845 based on the model of similar societies in Paris, Berlin and London. The maps formed part of a series of studies commissioned during the 1860s and 1870s on multi-ethnic imperial border regions. In the eyes of imperial administrators, the Polish Lithuanian Uprising of 1863-64 and the creation of the German Empire in 1871 raised concerns about the loyalties of non-Russian populations in the empire’s western borderlands. Ethnographic knowledge became a highly sought-after resource for gathering intelligence about these regions to use as evidence to bolster legitimacy for imperial rule.

Rittikh’s peers in the Geographical Society held his maps in high esteem. They regarded his work as an important contribution to knowledge. Readers in the Baltic provinces, however, reacted with condemnation. Rittikh was vilified in the local Baltic German press as a brash imperialist and promoter of Russian nationalism. Critiques slated his poor scientific research practices and subjective interpretation of statistical data. Rittikh greatly underplayed the presence of Germans and Lutherans and presented an exaggerated image of the Russian and Orthodox influence in the Baltics. In the text accompanying the maps, Rittikh argued for the close historical and cultural contacts between Estonians, Latvians and Russians. Germans, by contrast, were cast as foreign colonisers who had violently occupied the region since the 12th century.

Rittikh’s crude conclusions about the national and political loyalties of these communities based on their language and religion continues to influence perceptions of the region today, especially with respect to the majority Russian-speaking border cities of Narva in Estonia or Daugavpils in Latvia. Rittikh’s politicisation of language and claims about the deep-rooted kinship of the Baltic provinces with the Russian sphere of influence are echoed in Kremlin discourse about these territories being part of Russia’s ‘near abroad’. Moreover, Rittikh was also one of the first to term the Baltic provinces pribaltiskii krai ‘border territory by the Baltic Sea’. This appropriated the Baltics as an integral, natural part of the Russian state. The term pribaltika continues to be widely used in Russia to refer to the Baltic states. It has similar connotations to the practice of referring to Ukraine in Russian as na Ukraine to undermine its status as a politically defined territorial unit – equivalent in English to ‘the Ukraine’. These seemingly small distinctions remain critically important for shaping geographical imagination and asserting political sovereignty.

Influential though Rittikh’s maps were for shaping perceptions of the Baltic provinces, his was not the only voice. By the late 19th century, Estonian and Latvian mapmakers, thanks to high literacy rates and growing opportunities for social advancement, began to produce maps that challenged this imperialist outlook. One such mapmaker was Matīss Siliņš, a schoolteacher and publisher of popular calendars, who began regularly creating Latvian-language maps in Riga in the 1890s for mass audiences. While Siliņš did not go so far as to advocate Latvian independence, his maps consolidated the idea of a distinctive and vibrant Latvian territory within the Russian Empire. They signified a radical departure from seeing the Baltics only through the lens of Russian or German possessions or sphere of influence. Siliņš’ maps demonstrated how ethnographic cartography was not only a tool of imperial legitimation in the Baltic provinces but could also be a powerful means of expressing the political claims for Estonian and Latvian self-determination by the early 20th century.

Catherine Gibson is a Research Fellow at the University of Tartu, Estonia, and author of Geographies of Nationhood: Cartography, Science, and Society in the Russian Imperial Baltic (Oxford University Press, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed