Pirate Voyage | History Today - 6 minutes read

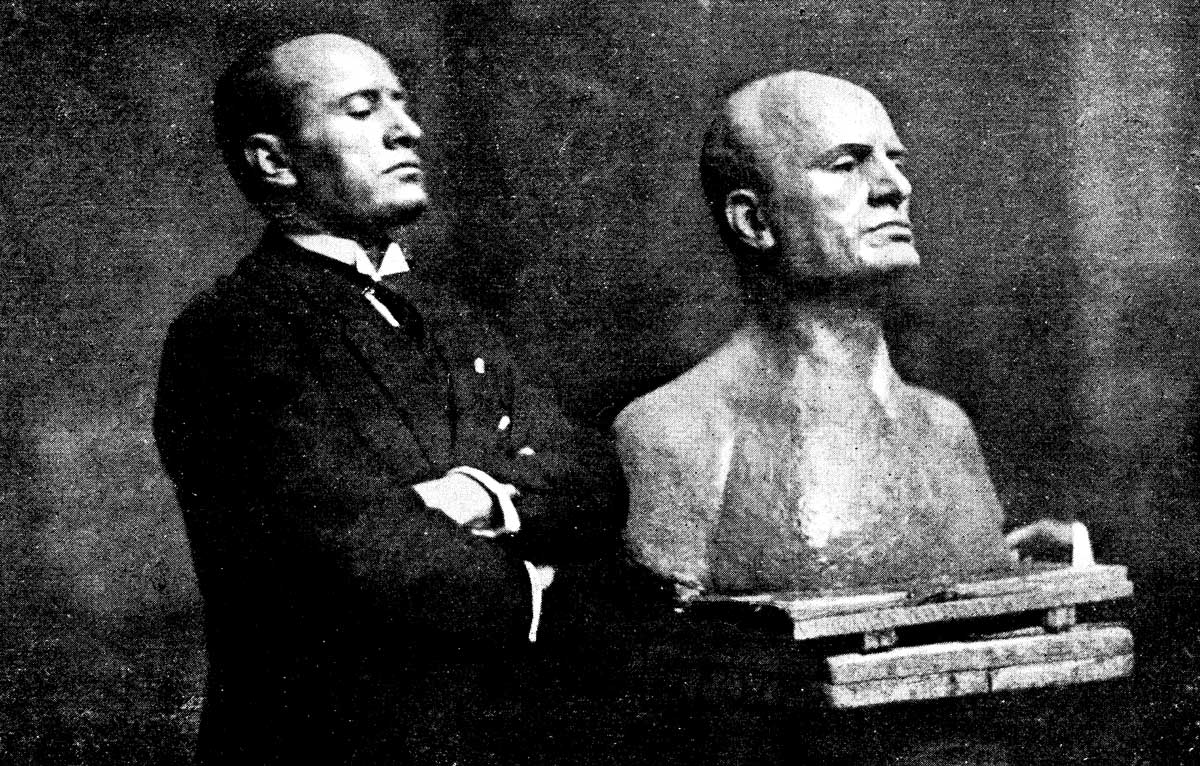

Two months before the March on Rome of October 1922, Benito Mussolini was faced with the first antifascist protest outside of Italy, which threatened to derail efforts to present his party as an acceptable newcomer in the international political arena. He reacted with fury. He warned the British government of ‘maximum degree’ retaliations if the British trade unions went ahead with their decision to boycott an Italian ship with a crew entirely made up of fascists.

The Emanuele Accame, an 8,000-ton cargo vessel, had been taken over by about 50 Blackshirts at Naples and illegally sailed for Cardiff. The Daily Herald of 23 August called it a ‘pirates’ voyage’, reporting under the headline ‘Fascisti sail FOR Cardiff!’ that:

owing to the occupation of numerous ships by the Fascisti and the constant clashes between the Port workers and the public forces in which several persons have been wounded, the authorities have ordered the complete military occupation of the Port. Before the latter took place, however, some of the Fascisti succeeded in occupying the ship Accame, and sailing, it is stated, for Cardiff.

It was unexpected for Blackshirts to have ventured abroad at such a politically sensitive time. Italy was in the middle of a turbulent summer. Social order was breaking down. The fascist advance was ongoing in the midst of a brutal campaign of intimidation. Mussolini claimed to have 300,000 men at his disposal. At the end of July armed squads had spread terror throughout the Romagna region in central Italy, setting on fire buildings associated with left-wing parties and trade unions and killing opponents in what looked like a rehearsal for the takeover of the whole country. Dramatically anticipating the actual event, a headline in Giornale d’Italia on 13 August stated: ‘Mussolini says that the March on Rome is underway.’

But a few obstacles remained in the Fascist party’s campaign to subjugate the socialist trade unions, in particular the Seamen’s Federation (Federazione Italiana dei Lavoratori del Mare), which had been led for over a decade by Captain Giuseppe Giulietti, one of the most powerful union leaders in Italy. As the Fascist party sought to impose its recently created National Corporation of Seamen, clashes arose between Giulietti’s men and the fascists.

The crew that had taken over the Accame were all members of this new corporation. What gave special significance to this voyage was the apparent intention to carry abroad tangible proof that this replacement of a socialist union with a fascist one was a new development to be accepted not only nationally, but internationally. A welcome in Britain of a fascist crew would, as well as dealing a humiliating blow to Giulietti and his federation of seamen, signal that ports around the world were ready to do business with the fascist crews. This would have come as a boost to Mussolini, who was hailed as having a ‘maritime spirit’.

Instead, the British unions announced a boycott of the ship. The call was raised by Robert Williams of the National Transport Workers Federation on 25 August while the ship was still off Gibraltar. A statement was issued: ‘Any attempt to load, discharge or bunker this ship will probably precipitate widespread strike action and it would be well therefore if she is ordered back to Italy and thus prevent grave and far reaching trouble.’

In Cardiff the Coal Trimmers Union promptly declared that ‘notices have been issued to all members of the Union and the general body of transport workers attached to the Bristol Channel Ports to the effect that there will be no loading or unloading of this ship’.

It was at this point that Mussolini threatened retaliation. The Fascist party secretary, Michele Bianchi, declared that they would use ‘every weapon of reprisal against those countries whose socialists intended to fight against fascism in Italy’, and would issue orders to fascists ‘to boycott by every means in their power any English steamers entering Italian ports’. Local fascist squads were on standby, awaiting orders to retaliate against British ships.

After these warnings, Bianchi made a startling move towards the British government. He requested an urgent meeting with the British ambassador in Rome. Coming from the representative of an armed party that was threatening to take over the government by force, this must have caused some concern at the Foreign Office. Nevertheless, the meeting took place immediately on 28 August. The British ambassador, Ronald Graham, was away so Bianchi was received by the chargé d’affaires, Howard William Kennard, who immediately reported to the Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon that ‘local fascista bodies might adopt an attitude which would provoke undesirable incidents and be injurious to British shipping interests’.

There is no evidence that pressure was brought on the trade unions to hold off the boycott as a result of this warning. But the following day, the eve of the ship’s arrival, news reached Cardiff from the National Union of Railwaymen headquarters in London that the boycott was ‘unofficial’ and had not been authorised. Even so, when the ship arrived under cover of darkness, the dockworkers refused to handle it. It was able to berth only because two sailors from another Italian ship provided assistance. The following day three representatives of the local unions, J.T. Clatworthy for the Coal Trimmers, A.J. Williams of the NUR and W.H. Rooney for the General Transport Workers, went on board to interview the captain, Umberto Mortola, to ascertain the situation and report to their headquarters in London.

By all accounts the captain put on a confident performance in good English, as he did in interviews with the press, who were greeted on board with the question: ‘Do we look like brigands?’

Acting on advice from union headquarters in London a compromise was reached. A list of demands was to be presented to the captain and crew. These included assurances that on returning to Italy they would refrain from taking part in anti-trade union action; that they would not get involved in acts of violence against trade unions and officials; and that they would not take any part in the destruction of property or in the destruction of printing premises of trade unions and labour journals. According to reports, a sworn statement was obtained by every member of the crew ‘from captain to cabin boy’.

The news was greeted by the Fascist party in Italy as a major victory. A few days later, Giulietti escaped from an attempt on his life. The systematic destruction of socialist trade unions continued. Had the British unions stuck to their initial decision to boycott fascist crews, history might have taken a different turn. With Mussolini undermined by doubts over his ability to lead a party and unable to guarantee the free flow of trade by sea, if fascist crews were not accepted, it is possible that King Victor Emmanuel III might have thought twice before calling him to Rome to form a new government.

Alfio Bernabei is a historian of Italy and the author of The Summer before Tomorrow (Castelvecchi, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed