‘Highbrows no longer ignore high fashion’: our first fashion editor - 7 minutes read

In other words, fashion week has barely changed in 61 years. “For the fashion critic, the sturm und drang of the Paris Openings follow on from the openings in Rome, Florence and London,” Alison Adburgham wrote in 1960. “Already she has an overdraft of fatigue from travelling, typing and long-distance telephoning, from parties and interminable talking … And yet she survives. She brings herself sufficiently alive to turn a confusion of impressions into a fusion of trends, from which she can distill the essential essence of the coming season.” The namedropping of glamorous destinations, while simultaneously giving the impression that covering the shows is war-zone-level challenging, the dash of performative ennui, and the obligatory twist of champagne: this is what being a fashion editor was and is, then and now. Alison, I couldn’t have put it better myself.

Adburgham, who wrote for the paper from 1954 to 1973, was the Guardian’s first official fashion editor and one of the inaugural generation of newspaper fashion journalists. The fashion editor – both the job, and the larger-than-life caricature that goes with it, up to and including Anna Wintour – was invented in 1947, when Christian Dior’s New Look collection turned what happened on the catwalk into news. Newspapers had become a more visual medium during the war, recognising the storytelling power of photography and propaganda; fashion could feed this new appetite for visuals. The 1957 film Funny Face placed editors in the spotlight of this newly high-profile world, with a lead character based on Diana Vreeland. In 1938, there were 90 journalists at the Balenciaga show; in 1957, Time magazine reported that 500 attended that season’s Paris couture.

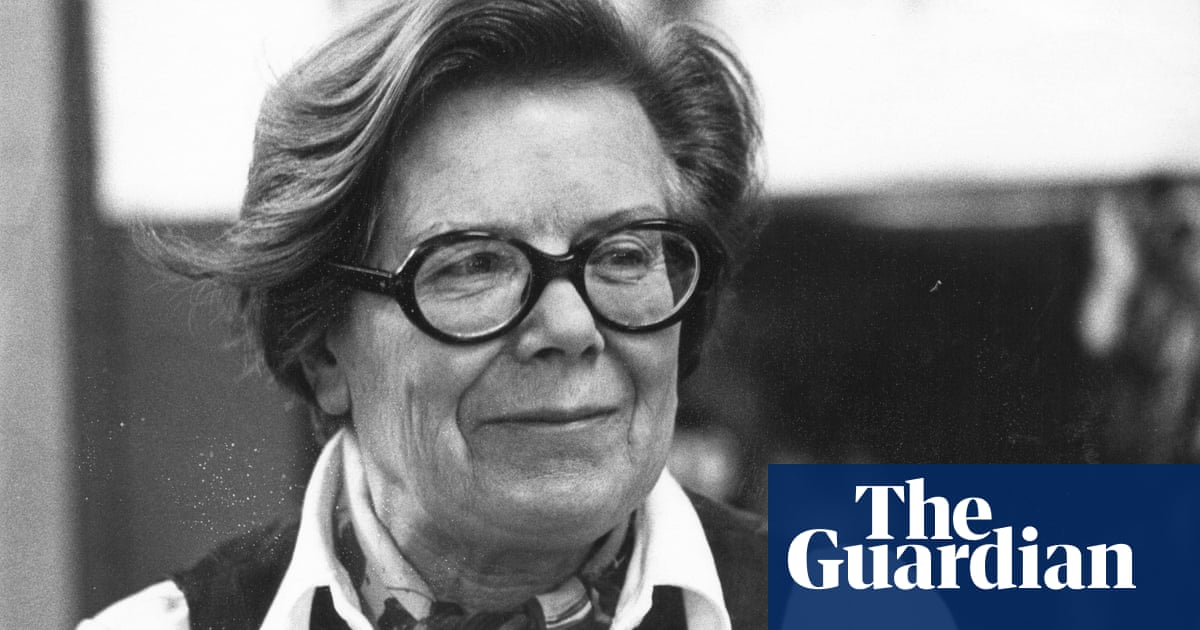

The earlier of the two surviving sets of photographs of Adburgham in the Guardian archives was taken in 1966. Her jacket is buttoned high at the neckline and nipped at the waist. She meets the camera chin-first, straight-backed and inscrutable as a Cecil Beaton model. The second, taken in 1973, is less formal. She is smiling, and her shirt collar wings out over a jaunty silk scarf. The two portraits neatly map fashion’s journey from the courtly era of Christian Dior to the louche language of Yves Saint Laurent, and also give us two sides of Adburgham. She had a crisp midcentury turn of phrase, confident in the imperious deployment of “one” as a pronoun. In 1961 she wrote that the secret of couturier Norman Hartnell’s allure was to combine “the respectability of the monarch with the shamelessness of the aristocracy”.

As a critic she was not afraid to bite: her review of a 1971 Yves Saint Laurent show (“a tour de force of bad taste … nothing could exceed the horror of this exercise in kitsch”) is the stuff of fashion legend. But she also had delicate antennae for fashion as zeitgeist, for the feel-it-in-your-fingertips stuff. In 1960 she writes that in contrast to the patented tailoring of the 1950s, “the silhouette of this new decade is sensed rather than seen. It has no clearcut outline … [fabrics] indicate but scarcely seem to touch the form beneath. The expression is lethargic.”

In 1956, she described a typical day at the collections: three hour-long shows in the morning, with 500 words written over lunch; another three shows in the afternoon written up at teatime. “It was more civilised in those days. There were no shows in the evening, so we would have an evening meal, together with a bunch of people,” recalls Moore. On grounds of industrial espionage, show attendees were allowed to take notes, but not to sketch – even a doodle on a programme could get you thrown out. A stark contrast to the shows of today, when the front row functions as a camera crew for an audience watching live on Instagram. Etiquette at London fashion week has changed a fair bit, too, it seems. In 1956, Adburgham covered a society fashion show where “there was a stipulation that, for dignity’s sake, no photographs should be taken of ladies with glasses in their hands.”

Travelling for the collections, as the shows were then known, was as deeply ingrained in the ritual of Adburgham’s year as it has long been in mine – or was, at least, until the pandemic shuttered catwalks, a year ago. The route was different, however. While the contemporary circuit has had New York, London, Milan and Paris as its fixed points, Adburgham’s stops were Paris, Florence and Rome. Florence and Rome, being where Italy’s most glamorous families lived, were the natural home of Italian glamour until mass-produced, ready-to-wear fashion overtook the art of couture and moved Italian fashion’s centre of gravity to Rome. Adburgham was an unflappable traveller, Moore recalls, who had enough French to be able to give the impression of being able to speak it in company. She was an intrepid one, too – one of the few to make the journey to New York by ship, in 1965, to see an exhibition of “the London Look” there. (“Such short skirts have never been seen in New York before,” she wrote.)

It is a curious aspect of life as a newspaper fashion editor in her time and in mine that the job means operating in two very different realms, and being an outsider in both of them. At the shows, the newspaper fashion editor is a workhorse among show ponies, skipping the air kisses as she frets about deadlines. But back in the office, the tables are turned: an outfit that is low-key for the front row looks like peacocking in the newsroom. I get sent invitations attached to helium balloons, or tucked inside bunches of flowers, or iced on to cupcakes. In the 1966 portrait of Adburgham, an invite with filigreed calligraphy sits among her notepads; it looks as if she has tried to hide it under an elbow. As a fashion editor in a newspaper office, you are, as Polan puts it, “one of the comic turns.”

“Fashion reflects the thinking of the day,” Adburgham wrote in 1960. Her fashion pages both mirrored and debated the increasing visibility of women, fashion having long been a way to talk about women’s public and private lives. “Over the last half-century there has been a complete change of attitude towards dress,” she wrote. “Intelligent women no longer feel it is only the unintelligent who are interested in clothes; highbrows no longer ignore high fashion.”

Adburgham brought brisk authority and a reporter’s eye for useful detail to the business of where to buy clothes – in 1971 she recommended a “white leather-look, showerproof coat in Vistram, can be sponged to clean. £9 15s at major branches of Marks & Spencer.” But she also wrote that what mattered most at Paris fashion week was “the impressions left not by the dress shows themselves but by the people in the bars and the bistros, girls on motor scooters, the children’s balloons in the Tuileries, the pictures in the Jeu de Paume, the shop windows, the smell of Gauloises, garlic and Arpège … fashion is part of the pattern, and the pattern has meaning because it is quickened by ordinary, everyday life.” From one fashion editor to another, there is no compliment greater than that Alison Adburgham did the job with style.

Source: The Guardian

Powered by NewsAPI.org