Medieval people suffered for fashion with their extremely pointy shoes - 7 minutes read

As many as one in three Americans suffer from bunions, those painful bumps that form on the outside of the big toe. Wearing high heels or ill-fitting shoes that cramp the toes can make the pain even worse, since constrained spaces increase pressure on the big toe joint. That doesn't deter people from wearing them, however. It's a well-established maxim that sometimes one must suffer in order to be fashionable.

According to a recent study published in the International Journal of Paleopathology, people in the European Middle Ages also endured pain in the name of fashion—in this case, with shoes with exaggerated pointed toes. University of Cambridge archaeologists studied skeletal remains excavated from Cambridge and found evidence that bunions were far more prevalent in remains from the 14th and 15th centuries than in those from earlier centuries, when more pragmatic footwear was popular. This may have increased the risk of suffering fractures from falls.

"We were quite fortunate that we happened to be studying a time period where there was a clear change in shoe fashion somewhere in the middle of our sample," co-author Piers Mitchell told The Guardian. "People really did wear ridiculously long, pointy shoes, just like they did in [the] Blackadder [TV series]." (You can see series star Rowan Atkinson sporting such shoes below and in this clip from the season 1 episode "Born to Be King.")

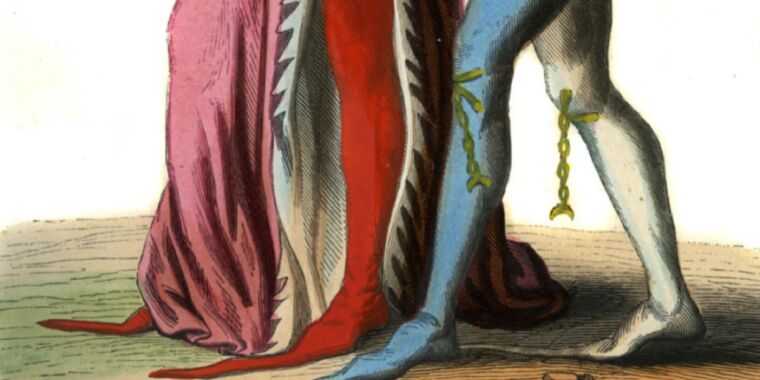

The shoes in question are known as crackows because they were thought to originate in the capital of Poland. They are also called pikes or poulaines (which can also refer just to the long pointed toe instead of the entire shoe). They came into fashion around 1382, when Richard II married Anne of Bohemia. Both men and women wore them, although the aristocratic men's shoes tended to have the longest toes, sometimes as long as five inches. The toes were typically stuffed with moss, wool, or horsehair to help them hold their shape. There is evidence in the literature from that period that people sometimes tied the toes up to the leg in order to walk more freely, although no archaeological evidence of the practice has been found.

It was a controversial fashion choice, with one 1388 English poem lamenting that men could no longer kneel in prayer because of the long beaks on their shoes. Charles V of France banned poulaines in Paris outright in 1368. And by 1463, English King Edward IV was so annoyed by the trend that he passed a law restricting anyone who was not nobility from wearing poulaines of more than two inches. The shoes were banned altogether two years later, and the trend died out completely by 1475 in favor of wide box-toed shoes.

The clinical term for bunions is hallux valgus, in which the joint connecting the big toe to the foot deforms because the big toe is bending too much toward the other toes. What causes this issue is not entirely clear. Some people might have a genetic propensity to bunions (because they have flat feet, for instance). But the condition can be exacerbated by tight shoes, high heels, and rheumatoid arthritis, among other factors, all of which can affect the biomechanics of how you walk, increasing pressure on the toes. Because the hallux plays a key role in maintaining upper-body stability, that joint deformity can impair balance and lead to an unstable gait pattern. ("Bunionettes" can also form on the outer base of the pinky toe.)

Back in 2005, archaeologist Simon Mays examined the skeletal remains of two British skeleton series; one was from the early medieval period, and the other was from the late medieval period. Mays found evidence of bunions only with the later remains, "consistent with archaeological and historical evidence for a rise in popularity, during the late Medieval period (at least among the richer social classes), of narrow, pointed shoes which would have constricted the toes."

The Cambridge team applied a similar osteological analysis to its own sampling of remains, since there is evidence that the medieval inhabitants of Cambridge also favored poulaine-tipped shoes by the late 14th century. The researchers also looked at whether there is a correlation between bunions and fractures likely resulting from falls.

The team examined the skeletal remains of 177 adults recovered from four cemeteries around Cambridge: 50 from a parish cemetery of All Saints by the Castle, 69 from one by the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist, 21 from one by the Augustinian friary, and 37 from a burial ground associated with Church End in Cherry Hinton. The examination focused on assessing the skeletal elements of the big toe for evidence of bunions. The researchers also looked for evidence of fractures, with the objective of establishing a possible link between bunions and injury from falls.

The results: 18 percent of all the skeletons the researchers examined showed evidence of hallux valgus. Among the remains that could be accurately dated, 27 percent of those from the 14th and 15th centuries showed evidence of bunions, compared to just 6 percent of skeletons that were buried between the 11th and 13th centuries. The highest prevalence was found among remains from the friary: 43 percent, compared to just 3 percent for the rural parish cemetery.

"Rules for the attire of Augustinian friars included footwear that was 'black and fastened by a thong at the ankle,' commensurate with a lifestyle of worship and poverty," said Mitchell. "However, in the 13th and 14th centuries, it was increasingly common for those in clerical orders in Britain to wear stylish clothes—a cause for concern among high-ranking church officials."

As for evidence of fractures, the Cambridge team found that fractures consistent with falls were far more common in the remains of those with bunions than those without, as well as being more common in the remains of older people with hallux valgus than those of the same age with normal feet. This is in keeping with modern studies.

"Modern clinical research on patients with hallux valgus has shown that the deformity makes it harder to balance and increases the risk of falls in older people," said co-author Jenna Dittmar. "This would explain the higher number of healed broken bones we found in medieval skeletons with this condition."

"Overall, the findings... would be compatible with the hypothesis that foot problems caused by the adoption of fashionable footwear had an impact on mobility and balance that resulted in an increased risk of falls within the community of medieval Cambridge," the authors concluded.

However, they acknowledged some limitations to their study. For instance, like similar studies that try to analyze and interpret fractures in human bones, such trauma accumulates over a person's life. Older people also often experience age-related bone loss, which brings a higher risk of fractures. So the high rate of fractures in the older samples could have had multiple contributing factors, not just falls caused by awkward, pointy-toed shoes.

"A narrow toe box can apply further pressure to the toes and push them into a different shape, much like wearing a corset," Emma McConnachie, a spokesperson for the College of Podiatry, told The Guardian. "The findings of the Cambridge team highlight these issues have been around for quite some time. It would appear that the fashion choices of the 14th century inflicted similar issues from footwear as we see presenting in clinics today."

Source: Ars Technica

Powered by NewsAPI.org