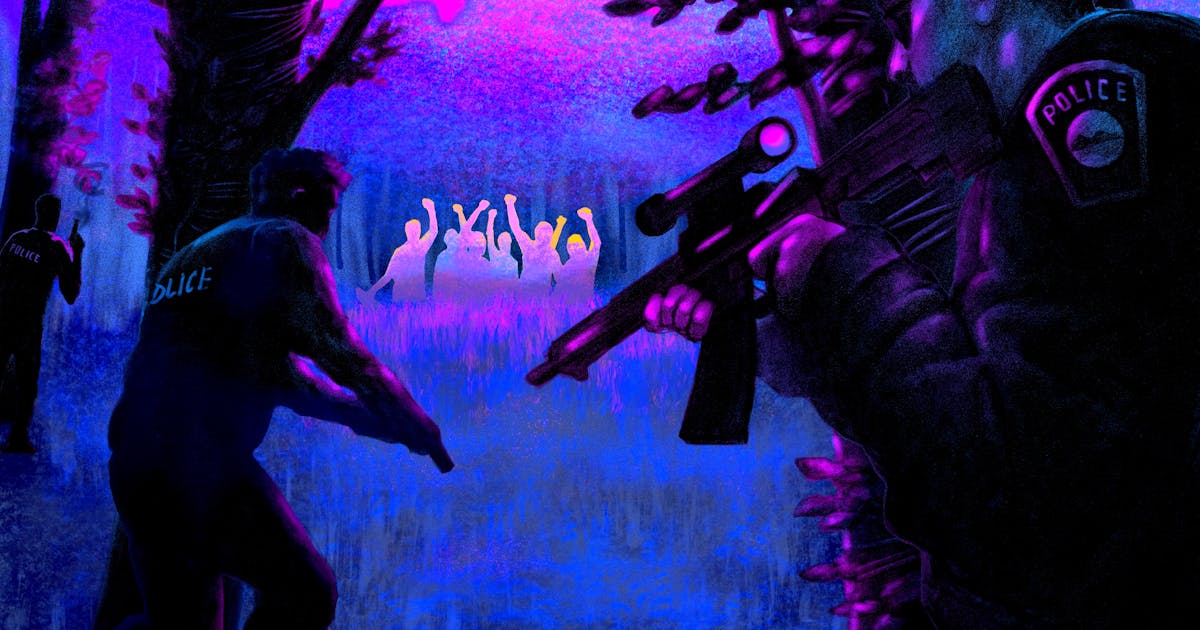

The Battle Over “Cop City” - 10 minutes read

Laura: You can

read The New Republic’s coverage of Cop City at newrepublic.com.

Alex: After

the break, we’ll examine the novel and disturbing legal strategies used against

Cop City protesters.

Laura: In

September, the office of the attorney general for the state of Georgia

announced that it was bringing RICO charges against 61 protesters of Cop City.

The RICO Act was

passed in the 1970s to help fight organized crime, and although harsh

crackdowns on public protest are nothing new, using provisions of the RICO Act

against environmental protesters is. Sarah Jones wrote about this new effort to

criminalize dissent for New York Magazine.

Sarah, welcome to the

show.

Sarah Jones: Thanks

for having me.

Laura: So the

state is trying to portray the protesters of Cop City as this dangerous group

of conspirators. Can you tell us who they actually are? What’s the origins of

this group?

Sarah: Right,

so the origins of this group, I think, come a little bit out of the 2020

uprisings and seem to be pulling from a lot of different activist networks in

the city. And I think the movement against Cop City was building on,

especially, the uprising around the police shooting of Rayshard Brooks in

Atlanta.

So, we’re talking about

people who the state is characterizing as anarchists in order to make this

argument that they’re therefore dangerous. From what I can tell, it’s a much

more politically diverse group than that. I don’t think they all identify as

anarchists at all, nor do they necessarily hold the same beliefs, follow the

same practices, what have you. It’s like any typical left-wing effort in that

way.

Laura: OK, so

just to break down some of the terminology that’s being used in these charges.

One thing is that they refer to a group called Defend the Atlanta Forest, but as

you flag in your piece, that isn’t really a group, can you just explain what’s

going on there?

Sarah: Yeah,

so it does repeatedly refer to Defend the Atlanta Forest, which it does

characterize as a group or an organization, as opposed to what it actually

seems to be, which is a group of social media accounts and activists that are

behind those accounts. But they don’t, as far as I can tell, belong necessarily

to the same organization with this banner.

Alex: Right.

There’s not like a formal group with membership roles here or something.

Laura: And I

guess the idea of portraying it as a more cohesive, organized group is to

create the impression that this is some highly disciplined conspiracy.

Sarah: I think

that’s exactly right.

Laura: Let’s

get into what those charges actually are.You highlight in the piece that one of

the charges involves an $11.91 reimbursement for glue, which is characterized

as an overt act in

furtherance of the conspiracy. Can you just take us through the indictment and

some of the accusations that are made in that?

Sarah: So

there were a lot of pretty small dollar charges along those lines. I picked one

of the lowest dollar amounts to make a point, but none of them were

particularly large and they were often like buying forest tools, buying kitchen

materials, glue, which

I’m not sure how that was going to be used.

But of course, in the tone

of the indictment, it’s this nefarious scary thing. So I think it was all to

make the argument that, first of all, these people are occupying the forest

when they shouldn’t be. So there’s this conspiracy to make sure that they can

dig in for the long haul, here in the forest [such as] conspiracy to put up

flyers in different places, just really trying to drive home the idea that

these people were all well-connected, that they had money, and were involved in

this conspiracy.

Alex: Yeah,

but isn’t it just a conspiracy to engage in legal protest?

Sarah: Yeah.

Alex: How

does the state justify, or how do they claim that this was a criminal

conspiracy?

Sarah: They

tried to link the 61 people who were named in the indictment to certain acts of vandalism, for

example. Specifically I think the claim was over like the vandalization of

construction equipment.

Laura: The

things that are listed are really not what you would expect to see listed in a

RICO prosecution because most people are used to thinking of RICO as charges

that are used to prosecute the mafia.

Were there any warning

signs that they were going to take this direction?

Sarah: It didn’t

come as a surprise to activists, no, they were expecting that something like

this was going to drop. The RICO indictment itself, I would argue, was part of

this escalating assault on protest and left-wing political activity around Stop

Cop City. A number of people have been charged with domestic terrorism based on

really flimsy evidence, like the police were looking for people in muddy shoes

and muddy clothing. And they were arguing that that was proof that they’d help

repel the police from a part of the forest. And in fact, a number of them were

also there for a concert. So, how you’re distinguishing between people who were

part of one group and who were part of the second group is actually quite

difficult. This is part of a long-running attack on the activism around Cop

City.

Laura: I want

to go back to protestors being characterized as radicals and anarchists. Tell

us more about what you think that framing is doing and how it is taking the

idea of someone who cares about the environment to something else that seems to

be ominous.

Sarah: Right.

The fact that the indictment really starts out with this argument that’s a

political argument about anarchism, I thought it was really interesting and is

part of one of the most disturbing things about the indictment. I think they’re

playing on people’s fears, absolutely. There is definitely a stereotype that I

would argue is not realistic or accurate that people who are anarchists

themselves are violent and represent a threat to the state … not true of

anarchists in general.

Alex: That

would be news to most of the anarchists I’ve known.

Sarah: Yeah,

same. That’s what I was thinking as I was writing this.

Alex: It’s

funny because it’s a very turn of the twentieth century kind of fearmongering

too though, right?

Sarah: It

really is.

Alex: There’s

a rich history here of fearmongering about anarchism in this country.

Sarah: Right

and then proceeding from this place to then argue that the practices of

solidarity and mutual aid and collective action are all part of this conspiracy

are really disturbing.

Laura: The

thing that seems particularly worrying is that if you can characterize these

things in criminal terms, you could just say anything about anyone because

there’s no logical link and doesn’t seem to be grounded in actual evidence. If

you can do that, then how can anyone ever protest anything legally?

Sarah: Right,

and I think that’s the point, isn’t it? I don’t think a lot of these charges

are going to stand, but the point was to chill political activity.

Laura: What

effects have you seen since the indictment came out on that front?

Sarah: People

are definitely afraid, and I would argue maybe that chilling effect is there, I

think it would be unrealistic for it not to, but the movement to stop Cop City

has not gone away, it’s still there.

Alex: What is

the public justification, the local political justification for doing this,

because I think that it’s clear that a lot of people in Atlanta do not

particularly want Cop City. How are local officials justifying this crackdown

on people protesting?

Sarah: So,

there have been a lot of arguments put forward in defense of Cop City and the

development in general. One of them was that this is necessary to improve

police morale and protect public safety in the area, which is what we commonly

hear in any defense of expanding the police.

That’s not so unusual, but

the activist Micah Herskind had an interesting piece in Scalawag Magazine where

he was essentially arguing that it was a way to say that Atlanta was open for

business, signal to other corporate elites and upper-class white communities

that it’s safe for them to open up new real estate markets for developers.

The idea that locals would

be somehow against those goals is really threatening to them and puts them in

the position where they have to argue that all these activists are out-of-state

agitators and they can’t possibly be from the local communities.

Alex: We’ve

seen that argument from local officials all over the country for the past

several years, in New York, in Minneapolis, wherever there has been protest.

Especially police officials and local politicians have been very quick to blame

these sort of amorphous and terrifying out-of-state agitators, which I always

find really interesting.

Sarah: Yeah,

it’s just unbelievable the idea that there would be just these roving bands of

anarchists with enough money to come in…

Alex: To

travel the nation.

Laura: Also

something that I think really interesting in the piece you wrote is that there

is a danger when an indictment like this comes out that the media will just

report that 61 people have been charged with conspiracy. It almost ties them

with the brush of being guilty because you can just report this as what the

prosecution says.

Sarah: Right.

I think this is the way the media approaches a lot of criminal justice issues

where there is this tendency to just believe whatever prosecutors or the police

are saying about a given case.

I would like to think that

maybe in the wake of the 2020 uprising, the press is a little more critical,

but I think it varies wildly from outlet to outlet and reporter to reporter,

whether or not that’s the case.

Alex: It

always seems to me that there are lessons that the national media in

particular, doesn’t just refuse to learn, but that they forget, right? I think

one of them is around trusting essentially what the police say. I mean, I

actually knew some of the protesters against the 2008 Republican convention in

St. Paul charged with felony terrorism, which

again, was a terrifying thing to face. Then by the time it actually went to a

courtroom, all the felony charges were thrown out, but it makes people much

less likely to want to actually go out there and protest things.

Laura: How do

you keep going when everything you do has now been recast as a form of criminal

activity?

Sarah: I think

it’s a good question, and I’m not sure what I would do as an activist in their

position. The RICO indictment was designed to be so sweeping that as you said,

it’s just criminalizing legitimate forms of political activity making it really

hard for people to go forward. It’s especially targeting the active occupation,

which is really central to left-wing protest. I don’t think that, like I said

earlier, that the movement against Cop City is going anywhere. But perhaps it’s

going to enter more of a regrouping stage as they figure out what they do next.

Laura: Why do

you think environmental protests have caused such a crackdown in this case? We’ve

seen crackdowns with pipeline protests too. What do you think is happening

there?

Sarah:

Building off of that piece in Scalawag Magazine, I would argue that it’s

because environmental activism is really challenging a lot of financial

interests in a direct way, and I think it causes especially elected to

Democrats—it forces them in a difficult position and reveals, I think, how

meaningless a lot of their stated positions are. Whether it’s a commitment to

police reform, whether it’s a commitment to environmental justice, and I think

it becomes an embarrassment for them. And I would guess that’s part of the

crackdown.

Alex: Yeah, I

think there’s something to that. I think that one reason the crackdown in

particular against environmental protests has been so severe is—not to

psychoanalyze too much—but almost a sense of guilt.

Sarah: Yeah. I’d

like to think they’re capable of feeling shame. Yeah, I was kind of optimistic

on my part.

Alex: Yeah,

maybe we’re completely off base, but I know how I would feel if I was in their

position.

Sarah: Right.

Alex: Sarah,

thank you so much for talking to us today.

Sarah: Yeah,

thank you so much for having me. It was great.

Laura: Read

Sarah Jones’s article, “The

Cop City Indictment Prosecutes Dissent,” at nymag.com.

Alex: The

Politics of Everything is co-produced by Talkhouse.

Laura: Emily

Cooke is our executive producer.

Alex:

Lorraine Cademartori produced this episode.

Laura: Myron

Kaplan is our audio editor.

Alex: If you

enjoyed The Politics of Everything and you want to support us, one thing

you can do is rate and review the show. Every review helps.

Laura: Thanks

for listening.

Source: The New Republic

Powered by NewsAPI.org