Lifting the Flap | History Today - 5 minutes read

We think of reading as a primarily mental activity. Medieval and early modern audiences saw reading as a physical activity as well. They did not just turn the pages of their manuscripts. They wrote in the margins, underlined and annotated, used blank spaces for recipes and handwriting practice, kissed religious images and copied out quotations. Pop-up science texts evoke a period when reading always meant physical engagement, and remind us that reading was – and still is – a physical, interactive experience.

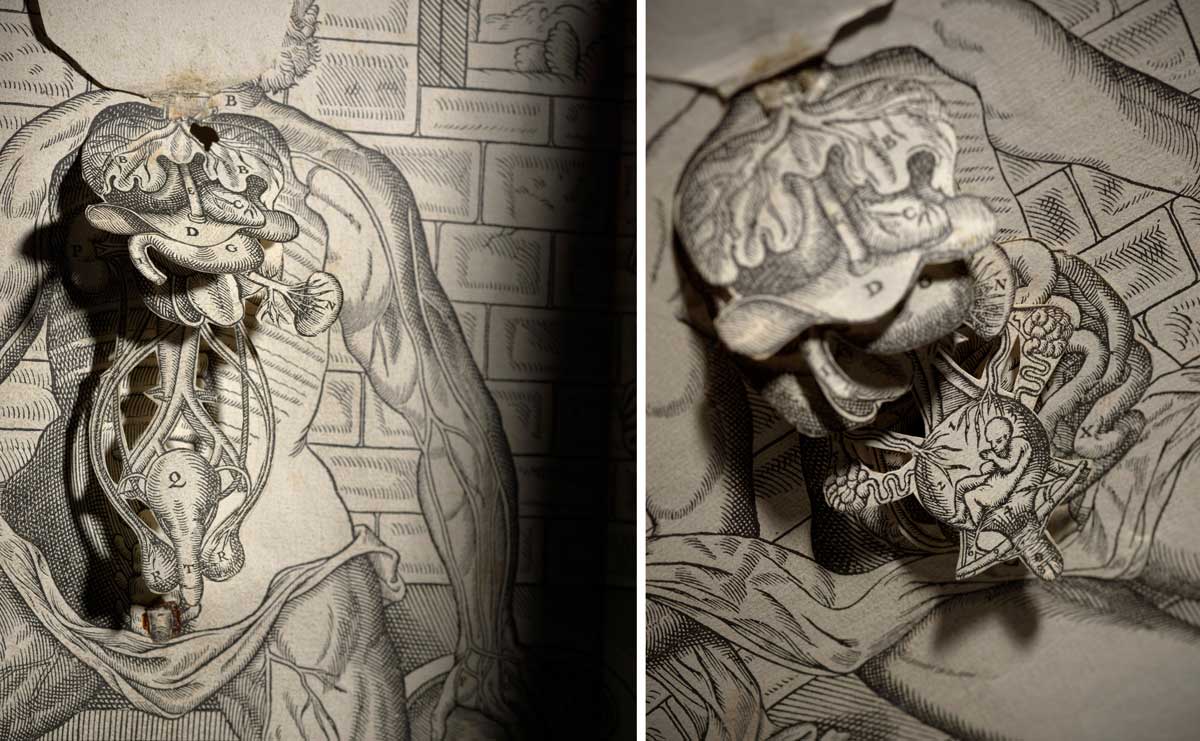

The first illustration of a body with liftable flaps was printed in Germany in 1538 by the printer and engraver Heinrich Vogtherr. An immediate success, pop-up anatomies were soon being published in France, Italy, the Netherlands and England; between 1538 and 1540 alone, at least 15 different editions were published in Europe. Most consisted of single sheets – known as fugitive prints – that could be bound into books or pinned to the wall. The figures in these prints all look very similar; they sit bolt upright, eyes wide open as if they were alive, but a curious reader can peel back their skin to reveal the layers of the lungs and liver, heart and guts, all the way to the thoracic cavity and spinal column. They were usually accompanied by extra materials, written in the vernacular rather than Latin. These texts can be considered rough summaries of university anatomical handbooks, but they were also elaborate, if crude, typographical artifacts designed for a popular audience. Most noticeably, the images dominate the text, which they sum up and simplify. Through these paper surrogates a non-specialist could, for the first time, delve into the furthest reaches of the human body.

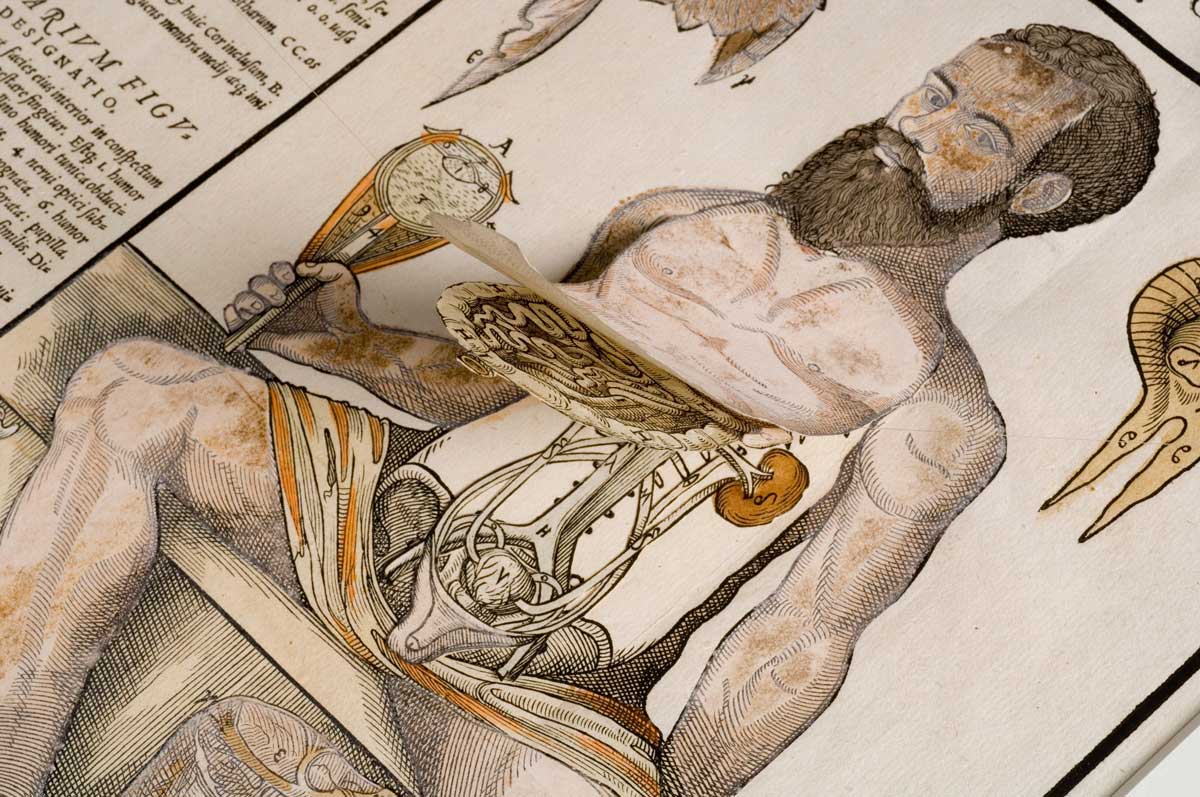

In 1538 Andreas Vesalius published the Tabulae, which was a set of six large sheets intended to be a memory aid for medical students. Before this, university manuals generally had few, if any, illustrations. The Tabulae, though, was in no sense a substitute for the direct observation of anatomical practice and the figures that accompanied its text would not enable anyone to acquire a real knowledge of the parts of the body. Although Vesalius recognised that the illustrations could not replace the real experience of dissecting bodies, the images nonetheless provided users with a very good ‘eye witness’ account to the dissection of a human body. Most anatomical texts, however, had few, if any, illustrations and the writing was highly advanced and intended for a specialist audience. By contrast, the pop-up prints pioneered by Vogtherr were attractive and striking and provided a more accessible substitute to the comprehensive and complex diagrams of Vesalius.

The first two fugitive anatomical sheets were printed in Germany in 1538: one by Vogtherr and one by the publisher Jobst de Negker. The elementary terminology, simplicity of the metaphors (the stomach described as a harbour, for instance) and the considerable space devoted to illustrations, as well as the fugitive sheet itself, suggest that these prints were intended for a non-specialist audience. The figures of both man and woman are based on one drawing, with only the head and paper flaps depicting the thorax and generative organs being different. Each organ is marked in Latin, with its vernacular translation added in the frame surrounding the fugitive sheet. There are some rudimentary anatomical-physiological notes, which one critic suggests could be attributed to Vogtherr himself.

Vogtherr’s texts are short, usually 12-18 pages in length, and are bound in a pamphlet style. Frölich, another printer who knew Vogtherr, reprinted the fugitive sheets in 1551-52, but coloured the figures to make them look less austere. There are also versions that started to include simple home remedies to accompany the sheets. In this form, they began to resemble medieval miscellanies and the role they played in the medieval household; that is, the inclusion of home remedies in the anatomical texts suggests that they were being used in private spaces not just university lecture halls and that there was, therefore, a general desire to know more about the inner workings of the body. This is perhaps most obvious in a popular fugitive sheet, which depicts a woman holding a sign with the words: ‘Nosce te ipsum. Knowe thyself.’

Fugitive sheets allowed their readers to reflect on the meaning of life and death and on the frailty and transience of the human body, as opposed to that of the immortal soul. Anatomy now reached a much broader section of society. All of their idiosyncrasies – the elementary terminology, vernacular language, lack of detail, pamphlet form, addition of colour and miscellany-style composition – demonstrate that their printers were responding to a call from non-specialists to know more about the human body, but, also, that printers were attracting and shaping readers’ interests.

Fugitive sheets by their very nature invite users to engage with these anatomical texts. As readers feel their way through the various paper flaps, they activate the image and thereby generate meaning from the bibliographic code, rather than passively receive a prescribed message. The fugitive sheet also coincides with 16th-century thinking on the idea of repetition, which was mobilised as a powerful metaphor, turning abstract ideas into permanent, verifiable knowledge. Because the paper flaps of these pop-up sheets offer infinite investigations, users are able to generate meaning every time they unfold the sheets.

Pop-up figures provided users with an ‘eye witness’ account to the process of dissection, but the accuracy of the anatomy mattered less than the image’s overall impressiveness. The prints simply needed to persuade their users of the importance of anatomical knowledge. This was a powerful way to communicate; through these images anatomical knowledge became accessible, literally graspable, to an audience who could not access knowledge about the human body through any existing class of publication.

Madeleine Killacky is a PhD researcher at the University of Bangor.

Source: History Today Feed