Doctoring the Ladies | History Today - 18 minutes read

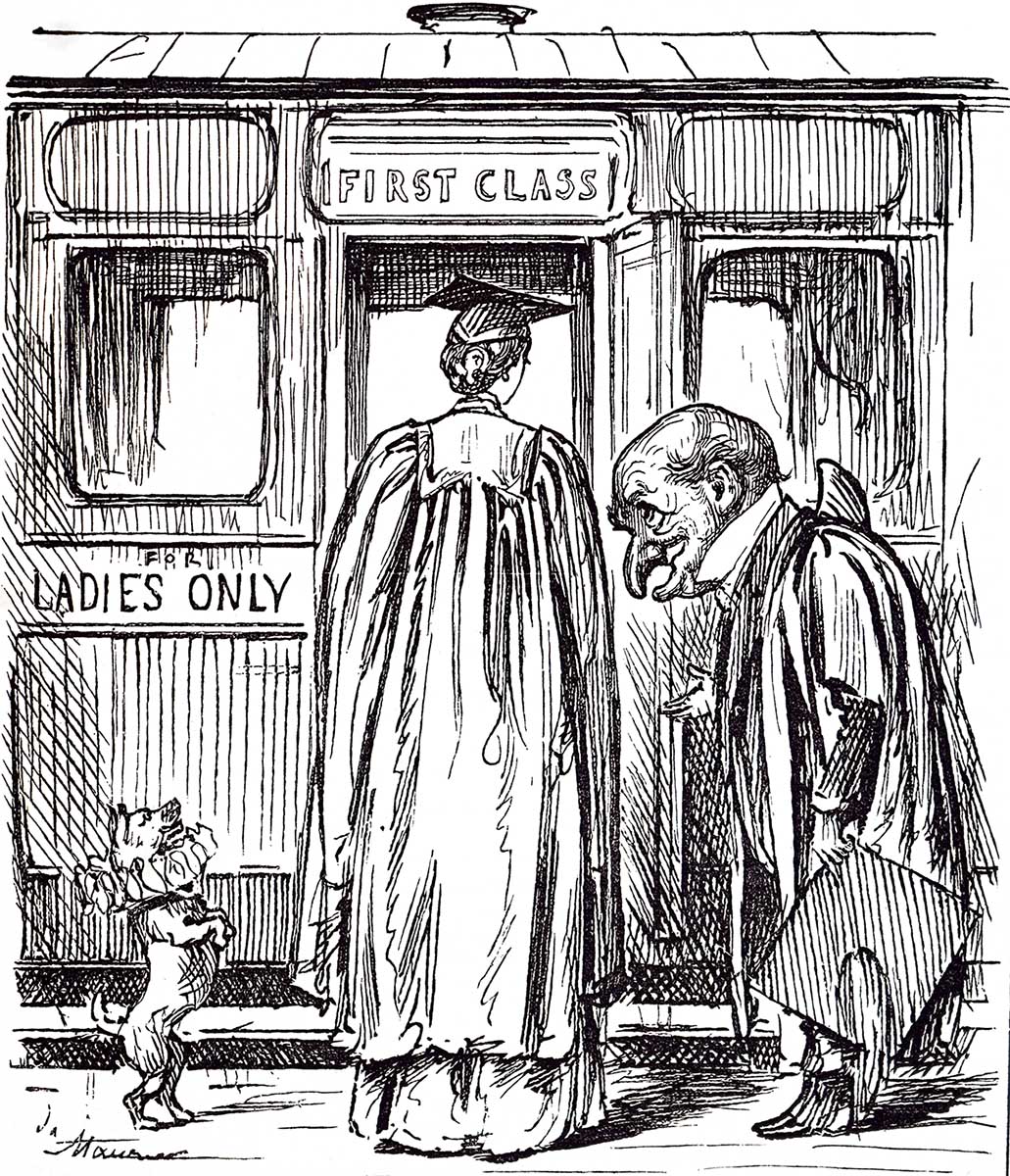

One might assume that an account of how 18th-century women participated in the life of the English universities (at that point restricted to Oxford and Cambridge) would be a very short one. After all, women’s colleges only began to open their doors at end of the Victorian era; women were first awarded degrees in 1920 (Oxford) and 1948 (Cambridge), with some colleges remaining closed to them until the 1980s. Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own gives a vivid account of their equivocal position in the early 20th century, describing a visit to ‘Oxbridge’ in which she is chased off the grass by a beadle and told that ‘ladies are only admitted to the library if accompanied by a Fellow of the College or furnished with a letter of introduction’.

In earlier centuries, the universities are normally seen as monastic and necessarily single-sex institutions, in whose history women appear only as monarchs and occasional patrons of colleges. Usually entered at a younger age than today, they served to prepare students for public professions (particularly the church) that were of course not open to women, while giving a gloss of learning to upper-class men who might leave without taking a degree.

Yet a look at some lesser-known writings of the time shows how, even in the long 18th century, the universities could be a source of interest, intellectual stimulation and flights of fantasy for women. The apparent dichotomy between ‘women’ and ‘the universities’ also formed part of contemporary debates about what kinds of learning and accreditation were worth having.

‘Worthy to be encouraged’

There were certainly some women, like the Anglo-Saxonist Elizabeth Elstob, who participated actively in scholarly life. Elstob transcribed and translated Old English texts in collaboration with her brother William, as part of a group of ‘Oxford Anglo Saxonists’ at the turn of the 18th century, and was later described by the antiquarian Edward Rowe Mores as ‘a female student of the university’. Although mainly based in London (where her clergyman brother had his living), Elstob appears to have had access to the libraries at both universities and had her translations printed by the Oxford University Press using a specially cast Old English type. Soliciting subscriptions for her in 1712, her mentor George Hickes wrote to the Master of University College: ‘I desire you to recommend her, and her great undertakeing to others, for she, and it are both very worthy to be encouraged.’

Elstob was highly aware of how fathers, husbands, brothers and male supporters might connect women to the universities. In 1709 she began a notebook compiling biographies of various learned women, a project that was continued in her friend George Ballard’s Memoirs of British Ladies, Who have been Celebrated for their Writings or Skill in the Learned Languages, Arts and Sciences (1752). One of Elstob’s (and Ballard’s) main sources was Anthony à Wood’s Athenae Oxoniensis, a biographical dictionary of writers and divines educated at Oxford from 1500 to 1690. Elstob recognised that, if read carefully, this apparently male-centred text could serve as evidence for women’s academic accomplishments and authorship. Indeed, the most complete sketch of her own life that Elstob left was written to supplement her brother’s entry in a projected continuation of Athenae Oxoniensis.

Although Elstob describes William as the great enabling force in her career, which was cut short by his death, such relationships were not simply a case of men generously sharing knowledge with their womenfolk. The classical scholar Elizabeth Carter, for instance, prepared her younger brother Henry for entrance to Cambridge over several years. Her friend Catherine Talbot advised her against excessive focus on him: ‘For pity’s sake, if you will be a tutor all your life, put on a coat and a square cap, and come and be a tutor at Oxford.’ This kind of imaginative cross-dressing, in which the scholar’s regalia was both tantalisingly accessible and out of reach for women, is a thread that runs through much writing in this period: all it takes to be a tutor at Oxford is a ‘coat and a square cap’ and the ability to wear them.

College life

Other women interacted with the universities as onlookers. The lively intellectual letter-writer Jemima, Marchioness Grey had connections to both institutions: her home of Wrest Park near Bedford was equidistant between them. On one 1743 visit to Cambridge, she describes her stay. Although it ‘rain’d almost Dogs & Cats’, Grey wished the weather to continue in order to prolong her visit, ‘for without any Partiality to Cambridge in particular, there is something to me inexpressibly pleasing in a College, & the Sort of Life it naturally leads One into’. The appeal of Cambridge for Grey clearly has to do with both architectural setting and a certain rhythm of routine and thought, which does not require her to be formally affiliated with the university.

This excursion was for the benefit of her young aunt Lady Mary Grey, who would end up spending most of her own life at Oxford. In 1744, she married David Gregory, who served as Oxford’s first Regius Professor of Modern History and Languages before becoming Dean of Christ Church, and she was thereafter a reliable source of academic news and gossip. At one point Jemima Grey joked that her eyes might be spared by involving the University Press in their correspondence: ‘Since Oxford will not furnish any better Ink to write with, will you be so good to send your Epistles to the Printing-House, that we may have at least a legible Edition.’

Proximity to these institutions could also breed contempt. Alicia D’Anvers, daughter of the first ‘architypographus’ (head printer) of Oxford University Press, was in her early twenties when she published two satirical poems titled Academia, or The Humours of the University of Oxford (1691) and The Oxford-Act (1693). Both are bawdy exposés of the university and its members’ habits, remarkable for their descriptive detail and bravura approach to rhyme and metre. As The Oxford-Act puts it: ‘Comprizing in immortal Sing-Song / How all th’ old Dons were at it Ding-dong.’

D’Anvers’ poems suggest that the monastic image of the university was a very thin veneer: while the senior fellows might be comically inexperienced (‘Should you a Naked Woman shew ‘em, / You’d fright ‘em so, ‘twould quite undo ‘em’), the undergraduates are constantly chasing after girls and being chased for debt by brothel keepers and mothers of illegitimate children. Certainly the gathering of hundreds of single young men together suggested that, in the absence of a respectable family tie, any connection that women had with them must be a sexual one.

A story about the actress and dramatist Susannah Centlivre, first recorded in a biography written 24 years after her death, for example, describes her at 15 being picked up by a student at the side of the road and then disguising herself as his ‘Cousin Jack’ in order to live with him at Cambridge. There, determined to ‘go away from College with a little more Learning than he brought thither’, Jack studied fencing, grammar, logic, rhetoric and ethics for several months before being sent away. Though potentially apocryphal, this version of Centlivre’s life served to emphasise her reputation for both intelligence and flexible morals – ‘the Charms of her Person and her Genius’. As noted by John Wilson Bowyer in his 1952 biography of her, the romantic narrative about the beautiful maiden at the roadside seems to have been widespread: in one variant, a girl named Susan studied at Oxford and took to it as ‘to the manner born’.

Academic Act

These duelling facets of scholarship and sexuality united in the ‘Oxford Act’, the subject of D’Anvers’ satire and one very public way that Oxford interacted with wider society. This was a ceremony conferring honorary degrees, which continues to this day in the form of the annual Encaenia, but was originally a much more elaborate spectator event involving musical performances and satirical orations. In 1750 the Oxford-based poet Mary Jones composed a verse epistle to her friend Charlotte Clayton, ‘On the Reasonableness of Her coming to the OXFORD ACT’, in which the event’s primary purpose is not to see the participants but to allow Charlotte’s beauty to be seen by them. She is urged:

To our Athenian Theatres repair,

And let the learn’d and gay admire thee there.

Inspire, and then reward some gen’rous youth,

Nurs’d in the arms of science, and of truth.

Women were an established part of the audience at the ceremony; D’Anvers notes their placement alongside the senior academics in the gallery, with the satirical speaker (the Terrae Filius) specifically attacking the ‘grave Doctors and fair Ladies, / As always at the Act the Trade is’. By the second half of the century, though, the ceremony had been reformed to be more decorous and closer to its present shape. The Westminster Magazine for July 1773 reports on the Encaenia of that year, which featured the installation of a new Vice-Chancellor and two evening balls and notes that: ‘The appearance made by the Ladies will long remain unequalled.’

The article that follows, however, argues that women should not only appear as a decorative part of the occasion, but should also be eligible for ‘Academical Honours’ of their own. It begins by recounting how ‘the Wits of the Town have made themselves extremely merry about a pretended incident … of a Lady’s being honoured with a Doctor’s Degree, under the appearance and habit of a man’. The writer is certain that this disguise is unnecessary, however, as many of the ‘fair Ladies’ who attended the Act would have been entirely capable of surpassing the men in oratorical skill and learning if this were open to them. He concedes that it might not be ‘altogether prudent for the different sexes to study in the same College or University: for … there are obvious reasons for thinking such a commixture of male and female Students would conduce little to their improvements in erudition’. Even if ‘custom excludes them from a College education’, however, given the honorary nature of Encaenia degrees the author sees no reason why women who have managed to succeed in literature should not be named as doctors and suggests the names of the prominent Bluestocking figures Elizabeth Carter, Elizabeth Montagu and Hester Lynch Thrale. ‘Would not Doctor THRALE, the wife, have sounded as well as Doctor THRALE the husband?’

If the ‘Doctoral Cap on the Ladies’ was a bridge too far, ‘they might be admitted surely … as Maids or Mistresses of the Arts’, to which end a list of prominent female authors and intellectuals, ranging from the historian Catharine Macaulay to the novelist Charlotte Lennox, were nominated for the degree of ‘A.M.’. Although part of the writer’s argument is the relative unworthiness of some of the men who have recently been awarded degrees, the ultimate effect is to highlight the range of female achievement excluded from university honours and the plausibility of their inclusion.

Montagu was clearly taken by the article, writing to Carter: ‘How do you do, Brother Doctor?’ Both, however, profess themselves more pleased by the brotherhood than the doctorate, with Carter replying: ‘Though I felt very little elevation from my appointment to the cap and gown, both my vanity and my heart were very agreeably flattered by my companion. ... I must feel pleased at finding myself united with you, even in a couplet of Tunbridge poetry, or a University degree.’ Montagu concluded that Carter, famous for her translation of Epictetus and often described by friends as a university in herself, would rather ‘chuse ye thing without ye affiche’ – real learning rather than external awards.

Flight of fancy

Other speculations took even further leaps than the Westminster Magazine. In issue 131 of the World (1755), the writer imagines a society in which all people could pursue the profession for which they were best suited and then has a dream in which his imaginings come true, bringing about a general revolution: nobles become shopkeepers and vice versa, fine ladies become sex workers and some women even ‘venture into the public, as candidates for fame and honours’:

One lady in particular … I saw marching with modest composure to take possession of the warden’s lodgings in one of our colleges; but observing some young students at the gate, who began to titter as she approached, she blushed, turned from them with an air of pity unmixed with contempt, and retiring to her beloved retreat, contented herself with doing all the good that was possible in a private station.

Even in this flight of fancy, a woman’s potential for academic leadership remains unfulfilled. As Harriet Guest has suggested, this figure bears some resemblance to Elizabeth Carter, who lived in seclusion at Deal and, in a letter to Montagu, lightly dismissed the idea of a professorship: ‘I never heard that any professor or professoress had any claim to the ornament of a blue ribbon, mere musty manuscripts, sine blue ribbon, have no attractions for me.’ Carter often alluded ironically to the combination of her scholarship and feminine preoccupations. She was infamously praised by Samuel Johnson for her ability to ‘make a pudding as well as translate Epictetus’.

In other texts by women, however, a greater range of activity was possible. In the early 1740s, the young Jemima Grey wrote to Catherine Talbot describing her discovery of a mysterious manuscript, while rummaging through the drawers at Wrest Park. The women were both fond of antiquarian papers, which they termed ‘Rums’ (an obscure cant word for an old book), but there are hints that this one may not be entirely genuine. Claiming to be set in the 1600s and using old-fashioned spelling, it is titled ‘The beginning & Progresse of the famous amoure betweene the Lord Viscount F-lkl-nd & the Ladie C-th-r-na T-l-b-t’.

This suggestively named heroine (helped by her friend the ‘Ladie M. Gr-y’) engages in a dramatic affair and elopes out of a window with her married lover. The pair settle in Oxford, ‘learnte Greek in a fortnighte, & read all the best authores together’; ‘all the Learned Men’ of the university come to visit them, so that ‘their house became a little College’. The story ends only after the lady ‘took her Degree the nexte Act in Oxford’ and ‘helde a Publicke Disputation in the Divinitie Schoole’.

Later known as a virtuous, serious-minded Bluestocking, Talbot’s real life had little in common with this lurid romance – that was probably part of the joke. Under the screen of a historical document, however, Grey creates a wish-fulfilment fantasy in which the official recognition of Talbot’s intellectual talents is put on an equal footing with success in love.

A decent proposal

The 18th century was a time of intense discussion about women’s education, with many writers, male and female, arguing that the sexes were separated by access to learning, not innate talents. Calls for separate ladies’ colleges dated back to Christine de Pizan in 1405 and were renewed in England in this period, whether actually founded (as in Bathsua Makin’s 17th-century school) or proposed (by the proto-feminist Mary Astell), or remaining in the realm of utopian narrative, such as those by Margaret Cavendish and Sarah Scott. Meanwhile, the prevalence of intellectual female friendships suggested ways that women could be collegial, even without a college.

At a time when the status of women came to serve as an index for societal progress and superiority, the lack of formal education opportunities was one area where Britain was lagging noticeably behind. Women receiving university degrees and giving lectures was not unheard of on the Continent. An influential ‘Essay on Woman’ by the Spanish writer Benito Jerónimo Feijóo, which was translated into English in 1765, listed several examples and was used by the Westminster Magazine as a precedent for ‘doctoring the Ladies’.

For the most part, however, the university narratives cited above were deliberately comic and did not seriously advocate for women’s admission as anything other than temporary visitors. Yet such speculative, counterfactual scenarios still served to expand the window of what was considered possible, perhaps helping to pave the way for later reform. Even while they remained a fantasy, it was one that demonstrated the significant role that women were taking in contemporary intellectual life – and the increasing difficulty of placing such women within established conventions of academic recognition.

Not worth knowing

Of course, the kinds of knowledge and recognition represented by Oxbridge were not always considered worth having. University scholars in this period were frequently criticised and parodied through association with pedantic myopia, which was at odds with the polite, sociable learning grounded in judgement and taste that many of these women sought to acquire.

In 1748 Jemima Grey gleefully reported on the reception of the ‘Mythraic Altar’ that she and her husband had built on their Wrest Park estate, which featured an ancient Greek inscription on one side and an attempt at ‘Persic’ cuneiform (which Grey enthusiastically determined to learn: ‘The Whole of it is Triangular, & they are dispos’d upon each other’s heads in the prettiest Manner you can imagine’) on the other.

On the very first day the inscriptions were installed, Grey writes, they had a lucky visit by two gentlemen from Cambridge, including the head of a college. This scholar, unable to ‘suppose the Characters upon a Stone to Lie’ is immediately taken in, examining it minutely: he ‘read a Lecture upon the Original Languages … & at last cried out with great Transport, “Oh! It is Boustrophedon!”’

The Cambridge man’s credulity is unshaken by the fact that the supposed altar is over six feet tall – if the question had been raised, Grey comments that: ‘One might easily have persuaded him’ this was proof ‘of the Larger Race of Men in that Age of the World’. While their laughter is good-natured, Grey’s enjoyment of the joke and the aesthetic qualities of the altar still trumps his university learning, which is unable to see the wood for the oversized tree.

An argument over aesthetics also informs the lengthy ‘Critical Dissertation’ that the writer Anna Seward composed in response to an essay on Alexander Pope’s translation of the Odyssey written by Joseph Spence, who became Oxford’s first Professor of Poetry in 1728. In her page-by-page rebuttal, Spence’s university position (which actually postdated the publication of his essay by two years) comes under particular attack, with ‘Professor’ eventually serving as a subtle term of insult.

Spence had criticised the ‘Beauties and Blemishes’ of Pope’s translation through reference to the original Greek, evaluating his text based on its accuracy, naturalness and elegance – in that order. Seward, however, considers this to be an overly ‘prosaic’ approach to a work of poetry. Instead, she seeks to defend Pope’s verse by comparing it with the canon of English literature and, particularly, Shakespeare and Milton. Her encyclopedic recall of Paradise Lost allows her to spot resemblances that Spence had missed, leading her to conclude: ‘I begin to suspect the Professor of Poetry at Oxford, knew not much more of the Greek, & Latin Poets, than his calling the passages & expressions, which Pope stole from Milton, “modern frippery,” proves he knew of the English ones.’

For Seward, who prided herself on her literary knowledge and critical acumen, it was the Oxford professor who was a pretender to learning. At the same time, what was missing from Spence’s assessment of Pope’s Homer was not simply a grounding in the right reading. She ends her essay with the assessment that: ‘The Professor was generally right when he reasoned, but that, from some defect of ear, or sensibility, his feelings respecting Poetry were blunt, irregular, & by no means to be trusted.’ What Seward thought she had, and Spence did not, was an inner capacity to evaluate literature that could not be institutionalised.

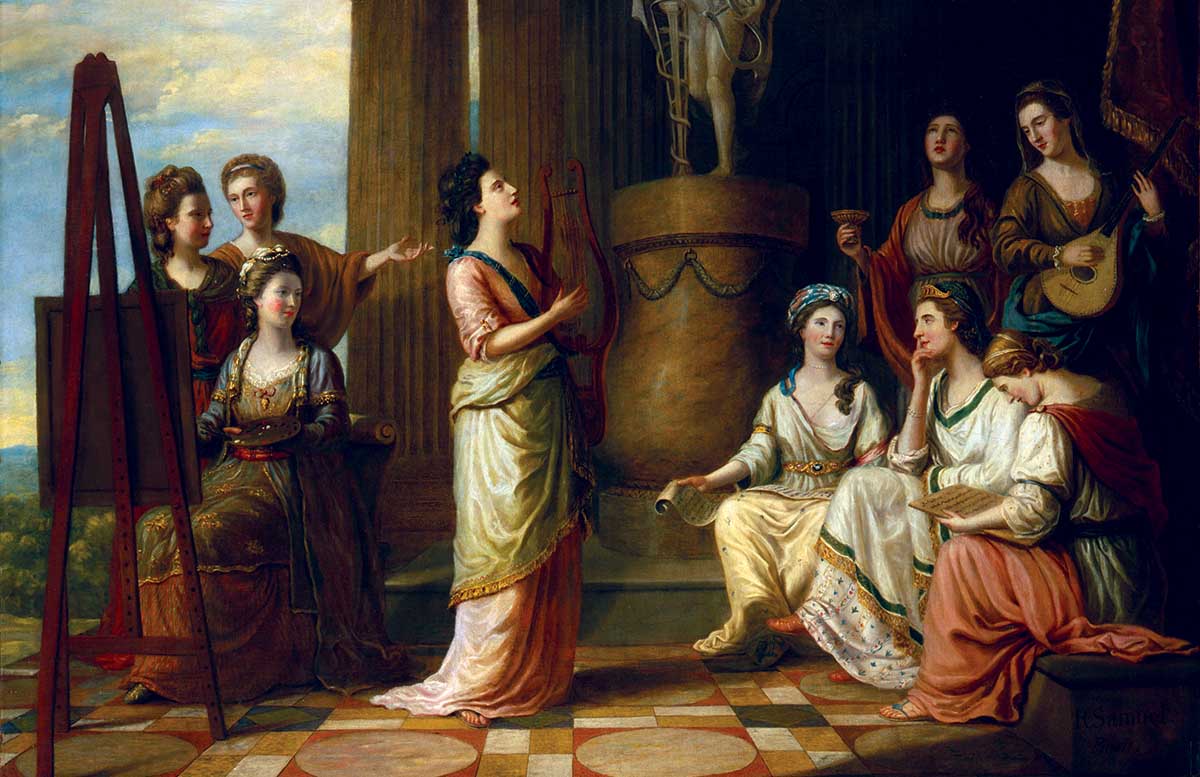

In ‘Of Essay Writing’, the philosopher David Hume had divided the world into the ‘Learned’ and the ‘Conversible’: the former domain dominated by men ‘shut up in Colleges and Cells’ and the latter by the ladies. Hume hoped to see a rapprochement between the two, making academia more accessible and conversation more intelligent. English literature, or what was then termed ‘Belles Lettres’, provided an ideal meeting-ground for the two, with Hume asserting: ‘I am of Opinion, that Women, that is, Women of Sense and Education … are much better Judges of all polite Writing than Men of the same Degree of Understanding.’

While it would be some time before English became fully established as an academic discipline, the substantial ability of 18th-century women to contribute to it suggests that there is no simple narrative of women eventually being ‘allowed’ to participate in Oxbridge education. Rather, they had a set of new and valuable critical skills, developed through independent reading, that they might bring to the universities. Their entry would not be a kind of academic drag-act, but a wholesale – and still in progress – transformation of what these institutions could be.

Natasha Simonova is a fellow and lecturer in English at Exeter College, University of Oxford.