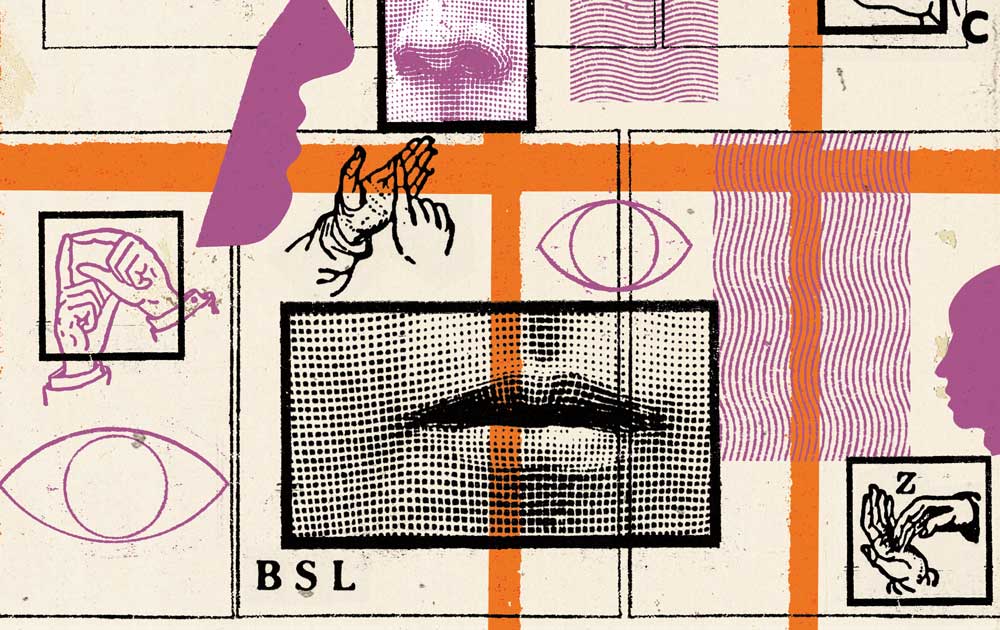

Sign of the Times | History Today - 8 minutes read

On 18 March this year thousands of people from the British Deaf community gathered at Trafalgar Square to support the British Sign Language (BSL) Bill on its third reading in the House of Commons. The BSL Act, which came into law in June, promised momentous change for the approximately 150,000 people who use BSL as their first or preferred language. By giving legal recognition to BSL, the Act ensured that public bodies had a duty to promote and facilitate its use, helping Deaf people to access public services. Of the UK’s minority languages, BSL has the highest number of monolingual users. The Act is also a powerful recognition of Deaf people as a cultural and linguistic group, helping to overturn decades of exclusion. (Deaf with a capital ‘D’ refers to people – most of whom are sign language users – who identify as culturally Deaf, while lower case ‘deaf’ describes people with hearing loss and is generally used in the history of deafness.)

It was only in 2003 that the UK government recognised BSL as a proper language rather than a ‘communication tool’, despite linguistic research from the 1960s onwards showing that British and American Sign Languages (ASL) were complete languages with rules of syntax and grammar. Failure to recognise BSL in the 20th century led to terrible educational outcomes for deaf children who struggled to lipread lessons and were forbidden from using ‘monkey gestures’ to talk to each other. A report in 2014 showed that deaf people had poorer health outcomes because they were often denied an interpreter.

Deaf exclusion

Speech, rather than hearing, has been at the heart of deaf exclusion throughout history. People who were born deaf, or were deafened before they learned to speak (prelingually deaf) were placed in a special category. Until recently the term used for these people was ‘deaf and dumb’, revealing contemporary beliefs about the intellectual capability of prelingually deaf people. Though considered offensive now, this language continues to appear in discussions of historical deafness.

In the largely oral world of pre-modern Europe, speech was important in various legal settings. Roman law codes argued that since deaf people could not voice consent, they should be treated as infants. This meant that deaf people could not inherit property, marry, make wills or take a case to court. The influence of the Justinian Law code spread these ideas throughout Europe and by the medieval period they were firmly entrenched in the legal traditions of different countries.

Henry Bracton, a 13th-century English cleric, argued in his book, On the Law and Customs of England, that deaf people should be classed with ‘imbeciles’ and ‘mad men’. By the Elizabethan period magistrates were routinely being told that prelingually deaf people were not responsible for their actions. In 1588 the antiquarian William Lambarde argued that: ‘There is no person to be punished to whom the Law hath denied a will, or mind to do harm’, namely: ‘he that is born both deaf and dumb’. In the following century John Bulwer, an advocate for deaf people, lamented the legal situation, complaining that prelingually deaf people were ‘looked upon misprisons in nature and wanting speech, are reckoned little better than animals’.

Comparing deaf people with children or animals reflected wider philosophical ideas about their capacity. Plato claimed that, since thought was articulated through speech, congenitally deaf people were incapable of rational thought. Arguments that humans and animals were separated by speech only heighted the belief that deaf people were cognitively impaired, displaying the now familiar double meaning of ‘dumb’. In the anonymous medieval poem The Pricke of Conscience, the author wrote about ‘the creatures that are dumb, and no wit or skill have’. The Enlightenment thinker Denis Diderot echoed this, asserting that people born ‘deaf and dumb … might easily pass for two-footed or four-footed animals’.

‘Speaking with the hand’

The justification for treating prelingually deaf people as infants was their inability to communicate. Except, of course, they could communicate using gestures and signs, a rudimentary form of sign language. Throughout history deaf people have talked to one other, their families and friends using their hands, bodies and faces – much like today’s BSL. While these conversations probably lacked the formal linguistic structures of modern sign languages, they allowed conversations between deaf and hearing people to take place. Some of the earliest mentions of deaf and hearing people communicating are from Ancient Egypt, with a text from c.1200 bc mentioning ‘speaking’ to a deaf person ‘with the hand’. In Jewish Palestine (c.530 bc onwards) it was recorded that in legal matters deaf people could ‘communicate with signs and be communicated with by signs’. Writing in the fifth century Augustine of Hippo described deaf people who communicated with each other and the hearing world through ‘bodily movements’, ‘gestures’ and ‘signs’. Challenging the idea that speech was essential for rational thought, he asked: ‘What does it matter … whether he speaks or make gestures, since both these pertain to the soul?’

By the medieval period signs and gestures were increasingly recognised as a legally valid alternative to speech. As well as giving deaf people a voice, this implied a belief that deaf people were capable of rational thought. In the 12th century Pope Innocent III issued a decree that allowed deaf people to make their marriage vows in signs; by the early modern period this was a widely accepted practice. In the 1620s one of the Church of England’s leading lawyers, Henry Swineburn, could point to several different legal rulings from across Europe to argue that: ‘They which be Dumb and cannot speak, may lawfully contract matrimony by signs, which Marriage is lawful.’

Complex language

What signs were people using in early modern England? In Leicester, one churchwarden recorded in detail the marriage ceremony conducted for a deaf man, Thomas Tilsey, when he married Ursula Russel in 1576:

For expressing of his mind, instead of words, of his own accord, [Thomas] used these signs: first he embraced her [Ursula] with his arms, and took her by the hand, put a ring upon her finger and laid his hand upon his heart and then upon her heart, and held up his hands towards heaven, and to show his continuance to dwell with her to his life’s end, he did it by closing of his eyes with his hands and digging out the earth with his foot, and pulling as though he would ring a bell, with diverse other signs approved.

This is one of many instances of deaf people using signs to communicate complex ideas with a hearing world. By the start of the 18th century there is evidence that the signs being used were not mimes (as in the marriage ceremony of Tilsey and Russel) but complex languages that required special interpreters. When the Abbé de L’Épée set up a school for prelingually deaf children in 18th-century Paris, it became apparent that his students already used a sign language that had its own grammar and lexicography.

‘Savage’ signs

The ability to communicate in signs was taken as evidence that deaf people were rational, but not by everybody. From the 16th century onwards many educators turned their attention to teaching children to assimilate into the hearing world by speaking vocally and reading lips.

In the mid-1700s a Spanish nobleman, Juan de Velasco, sent his two deaf sons to the monastery of San Salvador at Oña. There they met the monk Pedro Ponce de León, who taught the children to ‘speak’, in part so that they could inherit their father’s estates. Like many monasteries, the monks at Oña used a system of hand signals to allow them to communicate during periods of silence. This may have helped Pedro Ponce to teach the Velasco brothers. It was his success in getting the boys to speak vocally, however, that was celebrated, resulting in his work and that of his successor, Joan Pablo Bonet, becoming known throughout Europe and educators across the continent attempting to replicate their results. In Edinburgh, for example, Thomas Braidwood set up a school for deaf children in 1760. Braidwood’s school taught its pupils to ‘speak’, something described by Samuel Johnson as a ‘subject of philosophical curiosity’.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries these two different approaches to deaf education sat alongside each other, sometimes uncomfortably. While schools like the American School for the Deaf prioritised sign language, others promoted vocal speech (known as ‘audism’ or ‘oralism’). Vocal speech was increasingly seen as a mark of civilisation, with supporters of oralist education drawing on contemporary discussions sparked by colonialism and race to argue that sign languages were a form of ‘savagery’. In 1880 an international conference of deaf educators in Milan passed a resolution banning the use of sign language in schools, with devastating effects.

Bad beliefs

At the heart of oralism was a belief that the signs used by deaf people were a poor imitation of spoken languages. Representatives at the Milan conference described signs as ‘absolutely base’ and incapable of expressing abstract thought. That legacy persisted, with sign language only officially becoming part of D/deaf education in the UK in the 1990s.

Sign language is central to Deaf identity. Offering legal recognition to this language – one of the most widely used indigenous languages in the UK – not only allows Deaf people access to education, health and public services; it also recognises the humanity, culture and long history of the Deaf community.

Rosamund Oates is a reader in early modern history at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Source: History Today Feed