The Man behind the Leader - 6 minutes read

Bayard Rustin is the most important African American civil rights leader you have never heard of. Yet his legacy in overcoming racism, eradicating poverty and ending violence is unmatched by any other leader, with the exception of Martin Luther King Jr, a man whose legacy Rustin helped create. That Rustin spent much of his life in the shadows testifies to the enduring power of perhaps the only prejudice shared equally by white and Black Americans: homophobia.

Rustin’s homosexuality exacted a high price, both professionally and personally. He was America’s first intersectional radical. He was at once a civil rights crusader, a pacifist, a socialist, a trade unionist and, near the end of his life in the 1980s, a gay rights activist. He was drawn to ‘people in trouble’ – a phrase he used often – whoever and wherever they might be.

Born to a teenage single mother in 1912 in segregated West Chester, Pennsylvania, and raised largely by his Quaker grandmother, Rustin moved to New York in the late 1930s. After a brief flirtation with communism, he became a democratic socialist. Socialism formed the core of his radical agenda, uniting the poor and working classes of all races around a programme of economic and social equality, achieved through nonviolent direct action. Rustin seemed to be everywhere in radical circles during the 1940s and 1950s, but never quite in the leadership position that his talents merited. ‘Bayard’s problem’ was never far from his colleagues’ minds.

In January 1953, while on a speaking trip for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), the peace group for which Rustin had worked as an organiser for over a decade, he was arrested while having sex with two men in a parked car on a side street in Pasadena, California. The FOR’s leader A.J. Muste, a labour radical, a militant socialist and an uncompromising civil rights advocate, who considered Rustin to be his best organiser and regarded him as a surrogate son, nonetheless fired him immediately.

Seven years later, as Rustin served as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) New York office and special assistant to King, a jealous New York rival, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr, threatened to spread a rumour that King and Rustin were lovers. King and the SCLC African American ministers who made up the group’s constituency, unswerving in their commitment to the cause of racial equality, were much less forthcoming regarding homosexuality, which most of them regarded as a Biblical sin. Rustin was forced to resign from the SCLC and he and King ceased public contact.

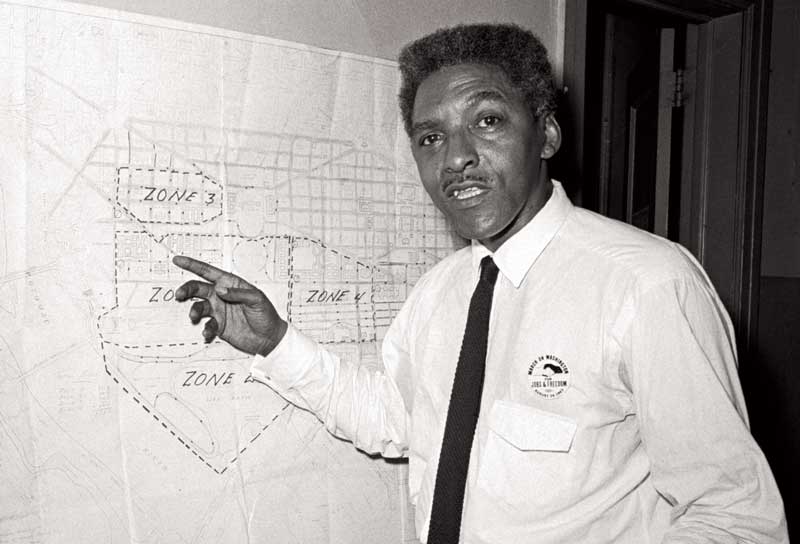

Everything changed, however, in 1963, as King planned the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the largest and most important event in the Civil Rights Movement up to that time. It would bring hundreds of thousands to the Mall and disorganisation, miscalculation, or – even worse – violence, could delegitimise the Movement as a whole in the eyes of a still-sceptical Northern white public. King knew only Rustin had the organisational skills to ensure that the March would come off as planned. Over the objections of many of the NAACP’s leaders, notably its executive secretary Roy Wilkins, King succeeded in having Rustin appointed as the March’s assistant director and de facto chief.

Rustin coordinated logistics seamlessly, arranging for transportation and food, security and sanitation services. He also recruited the speakers for the rally at the Lincoln Memorial that would conclude the March and arranged their order on the programme. The decision to place King last on the speakers’ list, putting him in the position to deliver what has gone into history as the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, was Rustin’s.

But once again, Rustin’s homosexuality became an issue. Two weeks before the March’s scheduled date, the segregationist South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond read details of Rustin’s 1953 ‘morals’ conviction into the Congressional Record and labelled him a sex offender during a speech on the Senate floor. This time, King refused to distance himself. And on the afternoon of 28 August 1963, thanks to Rustin’s organisation and King’s oratorical genius, the March on Washington became the most important moment in American civil rights history.

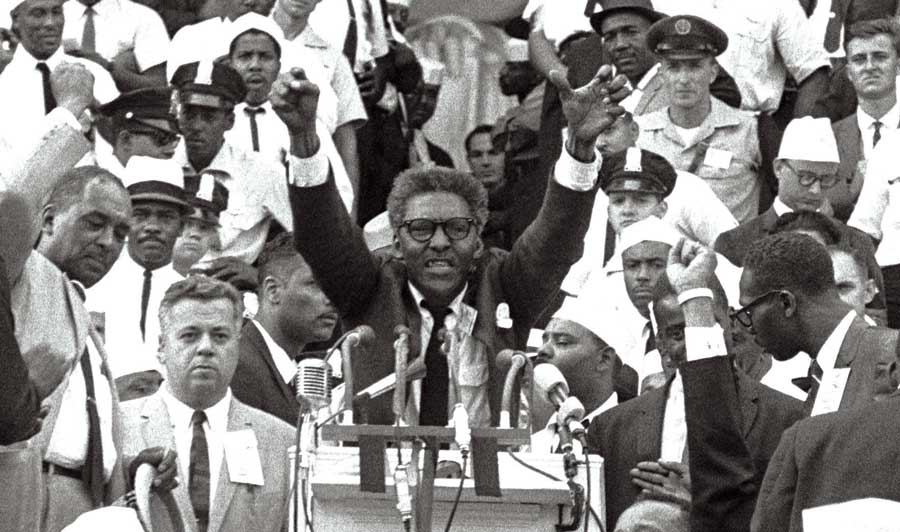

Rustin stood next to King as he delivered his address. Almost predictably, most images of King on the podium that day were taken from an angle that omitted Rustin and he rarely appears in photographs of the speech itself. Yet neither the speech nor that day would have happened without him. And minutes after King’s words ended the March, Rustin was called to the speaker’s podium to receive a lengthy standing ovation from the crowd of 250,000. A surviving photograph shows him standing joyously before the throng, his hands thrust triumphantly in the air.

Bayard Rustin’s homosexuality did not derail his career in radical activism in 1963, as it had just a few years earlier. This is a testament to the slowly changing sexual mores of the times. They would change even more rapidly later, particularly with the advent of the Gay Liberation Movement in the 1970s and 1980s, in which Rustin participated during the years before his death in 1987. After the March on Washington, Rustin became a much more visible public figure, featuring prominently in the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 – Rustin stood behind President Lyndon B. Johnson in the White House as he signed the latter – and serving as a valuable Democratic Party strategist. In 1966 he proposed a national ‘Freedom Budget’, guaranteeing government-sponsored jobs, incomes and medical care, that became the model for 21st-century progressive policy initiatives.

But Bayard Rustin did not completely emerge from the shadows until he was well into middle age. Rustin was 51 years old at the time of the March on Washington and we are left with a gnawing sense of what might have been for this supremely talented and charismatic man had he not spent the first decades of his activist career hamstrung by the homophobic prejudices of his fellow radicals. What could Rustin have accomplished had he been able to start earlier? An intersectionalist before his time, Rustin might have transformed America even more profoundly than did King had his own allies permitted him to do so.

Jerald Podair is Professor of History and Robert S. French Professor of American Studies at Lawrence University. He is the author of Bayard Rustin: American Dreamer (Rowman & Littlefield, 2008).

Source: History Today Feed