All That Is Not Good - 4 minutes read

When the news is full of images of suffering, it feels difficult – almost wrong – to concentrate on anything else. How can ordinary work, meetings, emails, teaching or writing matter, when the world seems on the brink of catastrophe?

As a writer, I take some consolation in remembering that almost every creative endeavour throughout history – every piece of art or music, every book, every work of serious thought – has been produced in troubled times, in the shadow of war, sickness, violence and personal or collective suffering. Writers and artists can reckon with that suffering and find ways to address it, even without speaking of it directly – even with their gaze turned away from rolling news.

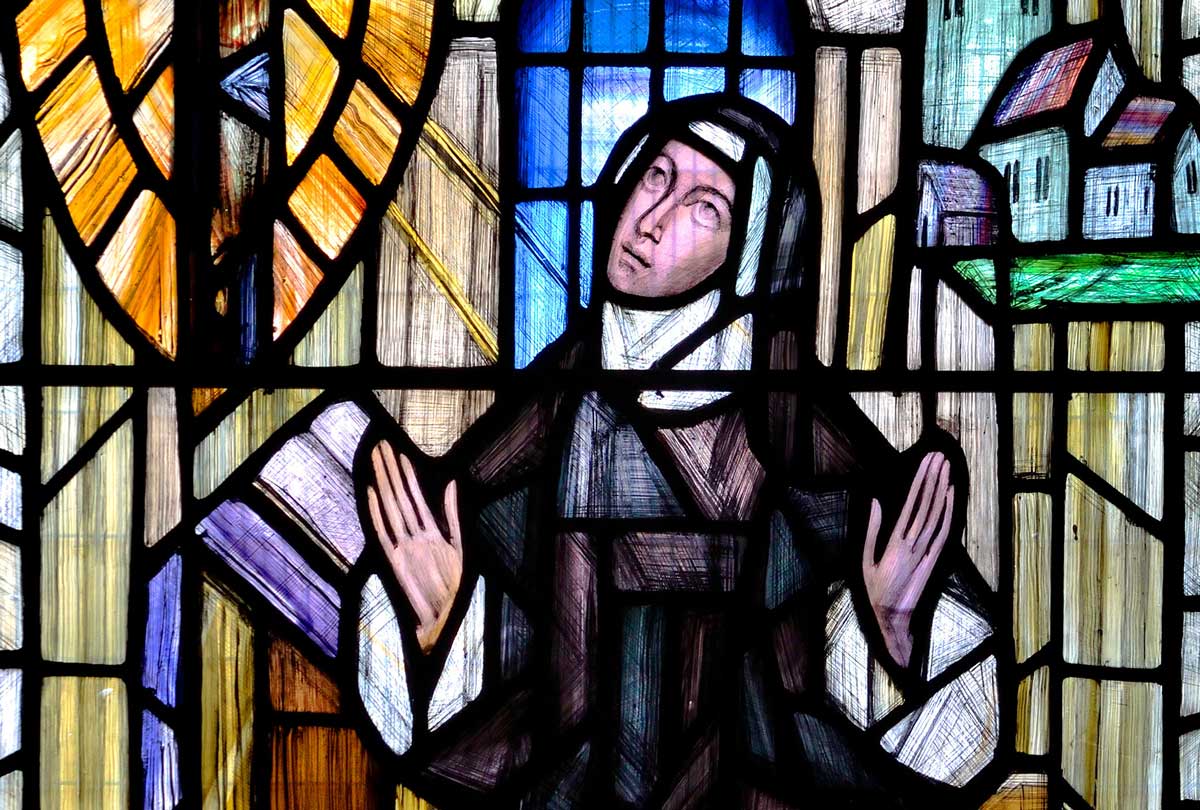

May 1373 was a troubled time, as much as any. Somewhere in East Anglia a young woman lay dying, her mother and her priest watching by her bedside. Julian of Norwich (as she would later become known) was 30 years old and her life had been lived in a time of plague and conflict. During her childhood the Black Death had raged through Europe; England was at war with France and political and social unrest was brewing. At only 30, she believed that her own life was over, though she felt she had so much left to do and accomplish.

Despite all expectations, she did not die. Instead, as her body ached and her sight failed, she received a series of visions, revelations of love in the very darkest moment of her suffering. The first was a living image of physical pain at its most intense and visceral: Christ bleeding and dying on the Cross, which Julian also understood to be, at the same time, an image of the most powerful expression of love.

Interpreting those visions, working out how to put them into words that could communicate their meaning, was to be her life’s work from that day on. She wrote and rewrote, weighing up her words, despite knowing that many people would prefer that a woman should not write about her thoughts or experiences at all. ‘But’, she says, ‘for I am a woman, should I therefore believe that I should not tell you the goodness of God, since I saw in that same time it is his will that it be known?’

Julian never mentions the troubles of her day, but she can’t have been unaware of them. As an anchoress, she had chosen to live in a single room attached to a church, devoting herself to prayer and meditation – in one sense, cutting herself off from the world. But that solitary vocation was not lived out in a lonely wilderness, far from human society. She resided in one of England’s busiest cities, to which visitors and news from Europe regularly travelled. From her cell the sounds of the city outside could be heard, the bustling life of a medieval parish church going on just next door. She also had visitors, who sought out the counsel of a wise woman known to be ‘expert’ in spiritual matters (as one visitor described her).

That dual existence, close to the world but not bound to it, was an anchorite’s special vocation and it shaped how Julian understood the message of her visions. To her, it was crucially important to say that God was not detached from everyday life, but present in all that she calls ‘homely’: in the ordinary and familiar, the domestic sphere, or the bond between a mother and her child. All those things can offer glimpses of goodness, comfort dwelling alongside labour and pain.

Julian is most famous for her faith in God’s words to her: ‘Sin is cause of all this pain, but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.’ People often quote this without the reference to pain and sin (which she defines simply as ‘all that is not good’), yet for Julian they can’t be separated. For her, consolation only has meaning because it takes pain seriously. From her tiny cell, in which the suffering world was largely invisible to her, she developed a theology of pain – not by reflecting on any particular case of suffering, even her own, but by exploring how pain intersects with, or teaches us about, love. Pain is everywhere but it is love, she believed, that is unconquerable: ‘He said not’, she reported, ‘thou shalt not be tempested, thou shalt not be travailed, thou shalt not be diseased, but he said: “Thou shalt not be overcome”.’

Eleanor Parker is Lecturer in Medieval English Literature at Brasenose College, Oxford and the author of Conquered: The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England (Bloomsbury, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed