Are You Not Entertained? | History Today - 5 minutes read

The chariot scene from Ben Hur (1959) remains one of the most spectacular moments ever committed to celluloid. Costing around a quarter of the film’s total budget and shot using a team of 70 specially trained horses on the largest film set then in existence, the scene brought to life the decadence and spectacle of the ancient Roman world in a way that seemed only possible on the silver screen.

This scene, though, did not originate in Hollywood. Sixty years earlier, in 1899, a production of Ben Hur had opened on Broadway based on the original novel by General Lew Wallace. In 1902 Arthur Collins brought the play to London’s Drury Lane. The epic chariot contest between Judah Ben Hur and Messala had 16 live horses race across the stage on a specially built treadmill.

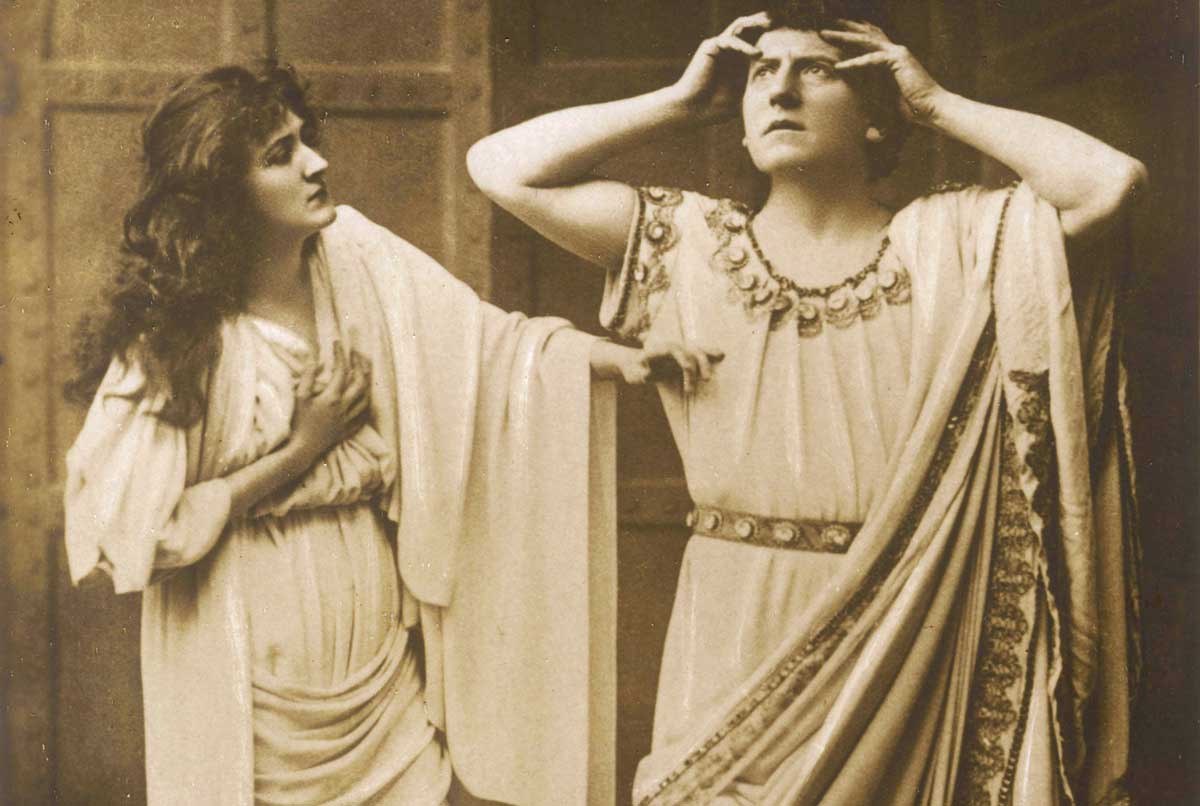

Ben Hur was one of many stage productions from the 1880s and 1890s set in the ancient world, which became known collectively as ‘toga plays’. In an age remembered for the more reserved and realist drawing-room dramas of Ibsen and Wilde, toga plays were a feast for the senses. Their special effects, spectacular scenery and decadent costumes were often recreated in exacting historical detail with input from ‘Olympian’ painters, including Frederick Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema and antiquarians, such as Sir Charles Newton. Toga drama often featured melodramatic plots involving depraved Romans in conflict with pious Christian heroes.

One of the earliest toga plays to tour Great Britain was Claudian (1883). Set in Byzantium in AD 360, just as it became the new capital of the eastern Roman Empire, Claudian tells the story of a young nobleman, cursed for his wickedness to eternal youth and beauty by a priest. Eventually, after more than 100 years of depravity, Claudian learns morality and selflessness, sacrificing himself for love of the young Christian woman Almida.

The play was an instant success and received rave reviews from critics such as John Ruskin and Oscar Wilde. Wilde saw in Claudian a kind of ideal version of his own aesthetic philosophies, praising it as ‘not merely perfect in his picturesqueness, but absolutely dramatic also’.

Indeed, Wilde would later publish his own tale of a decadent young man cursed with eternal youth and beauty in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), which perhaps owes more than a little to Claudian.

As well as popularising the toga play genre, Claudian would also catapult its leading man to international fame. Wilson Barrett went on to write and star in more toga productions including The Sign of the Cross, loosely based on Henry Sienkiewicz’s novel, Quo Vadis (1895). Once again Barrett’s character – the aptly named Marcus Superbus – struggles with his awakening conscience, this time at the court of Nero and his wife Poppaea. The spectacular finale takes place in the gladiatorial arena with a romantic and religious affirmation for Marcus as he is led to the lions. In reality, where Roman sources such as Tacitus mention Nero having Christians dressed in animal pelts and set upon by dogs, it was The Sign of the Cross (following later fourth-century Latin historians) that popularised the image of Nero feeding Christians to lions and the idea that ‘The cry, “Christians to the lions!” was heard increasingly in every part of the city.’

Barrett took his productions on tour to Canada, Australia and New Zealand, earning large sums not only from ticket sales, but from merchandise, including highly illustrated souvenir programmes, sheet music, rosaries, novelisations and a ‘Wilson Barrett Birthday Book’ of photographs. He amassed an adoring fan base, many of whom were captivated by his legs, which he often showed off in short tunics and wedge sandals. Notable fans included Queen Victoria – who wrote to Barrett asking him for souvenir photographs – and the prime minister William Ewart Gladstone, who saw The Sign of the Cross in Chester and wrote to Barrett that: ‘You seem to me to have rendered, while acting strictly within the lines of the Theatre, a great service to the best and holiest of all causes, the cause of Faith.’

The secret to the toga play’s success was its combination of spectacle and religiosity. From sets that broke apart to simulate earthquakes, to recreating the most lavish excesses of the Roman court, audiences could indulge in aesthetic delights while relishing the plays’ emphatically Christian morals. This proved too sentimental for some. One writer, G.W. Foote, quipped that toga play audiences ‘might be called a congregation’ in which people ‘walked as though they were advancing to pews’. Likewise, George Bernard Shaw called The Sign of the Cross a ‘tremendous moral lesson’ but added that ‘I am pagan enough to dislike it most intensely’. He went on to write a parody play, Androcles and the Lion (1912), which poked fun at the ‘shuddering exultations’ of Barrett’s Christians.

The spectacle of the toga play made it a perfect candidate for the screen. These adaptations, including Ben Hur, often retained the religious undertones of their toga play predecessors. Film technology offered new potential for special effects and spiralling Hollywood budgets soon looked beyond the toga play originals to historical figures such as Spartacus (in 1960) and Cleopatra (1963) for even more sumptuous spectacle from the ancient world.

Laura Eastlake is Senior Lecturer in English Literature at Edge Hill University and author of Ancient Rome and Victorian Masculinity (2019).

Source: History Today Feed