Dangerous Reds - 6 minutes read

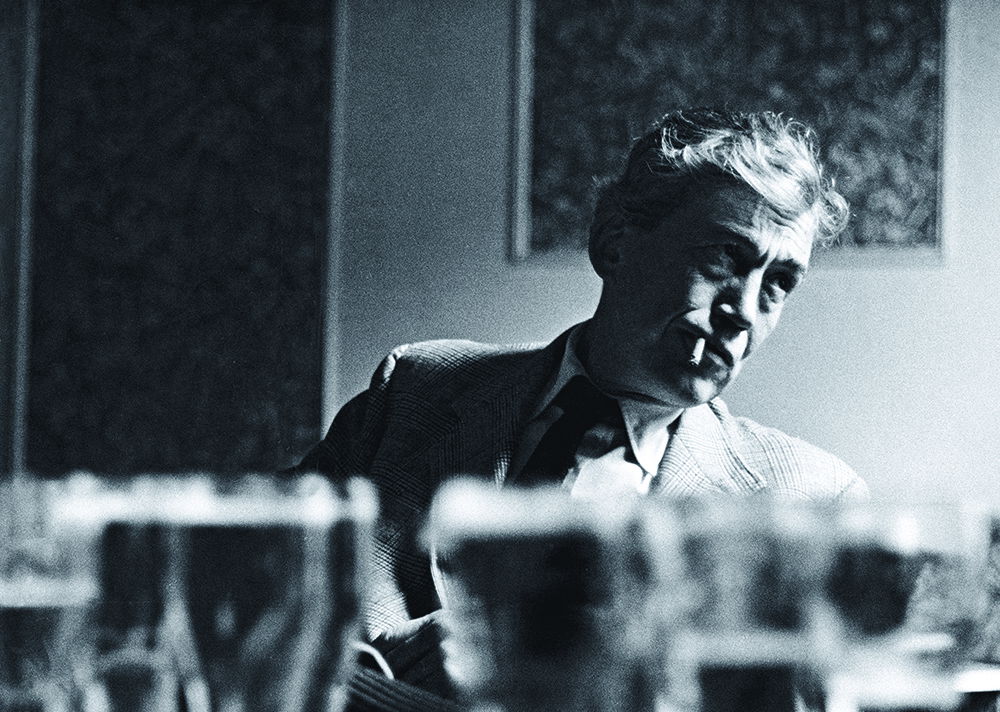

Targeted as a ‘Red’ by Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, John Huston did not enjoy the Los Angeles premiere of his latest film, Moulin Rouge, in 1952. Supporters of Senator Joseph McCarthy – the chief anti-communist witch-hunter in Cold War America – paraded outside the theatre with placards decrying him a ‘communist’. Huston was no friend of the Soviet Union, but he hated bullies such as McCarthy, who had hijacked the House Un-American Activities Committee two years earlier.

Before McCarthy famously, and falsely, declared that the State Department was ‘thoroughly infested with communists’, in February 1950, the Un-American Activities Committee pounced on Hollywood, looking for ‘friendly witnesses’ who would name those in the film industry they thought might be communists. In 1947 the ‘Hollywood Ten’ – a group of alleged fellow travellers – were summoned to appear before the committee over their suspected links to the Communist Party. Huston was a founding member of the Committee for the First Amendment in support of the Ten and, initially backed by many in the Hollywood community, or so he thought, he argued that Americans had a constitutional right to freedom of speech and political affiliation. For Huston, the committee’s proceedings were unconstitutional: congressmen did not have the right to effectively put citizens on trial.

The mood in Hollywood changed, however, when the Ten refused to directly answer the question: ‘Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist Party?’ From this moment, Huston remembered, there were very few who failed to succumb to ‘the fear, hysteria and guilt’ stirred up by the anti-communist persecutors.

Disgusted at ‘the evil’ being done in America, he decided to live in Ireland. Huston first visited Ireland in 1951 as the guest of a Guinness heiress and met the journalist Claud Cockburn, who was also in McCarthy’s sights. Cockburn and his family had moved from London to a small town in County Cork when McCarthy named him as one of the ‘most dangerous Reds in the world’ – from a list he had compiled of 269 supposed communists. Cockburn, whose MI5 file is gigantic, had been a member of the British Communist Party when he edited The Week, which pilloried the well-connected appeasers of Hitler he called the ‘Cliveden Set’. The Week’s subscribers, according to rumour, included ‘the foreign ministers of eleven nations’, all the embassies in London and Charlie Chaplin.

In Ireland, Cockburn, now a retired, but unrepentant, communist, wrote a novel under a pseudonym, Beat the Devil. By chance, while staying as a guest of Oonagh Guinness, Huston found this book, the only one on the nightstand, beside his four-poster bed. He read it and decided to turn it into a film script. An off-beat comedy, Beat the Devil (1953) starred Humphrey Bogart – who had won an Oscar for his role in Huston’s The African Queen (1951) – Jennifer Jones and Gina Lollobrigida. Before the film’s release Huston wondered whether the public would find it as funny as he did. They did not: it flopped. However, Beat the Devil later acquired a cult following with cinema audiences. As the author of the book, Cockburn did relatively well, to the relief of the bailiffs on his back.

Being listed as a ‘dangerous Red’ – he came in, to his disappointment, at around 84th in McCarthy’s list – did not bother Cockburn. The Irish, he wrote, loved nothing more than drama, and the locals in Youghal seemed pleased to find someone famous among them. When Cockburn’s friend Otto Katz ‘confessed’ to being a British agent at his Stalinist show trial in Czechoslovakia in 1952, he had to name a recruiter – someone out of harm’s way. He chose Cockburn, ‘Colonel Claud Cockburn’. In Ireland, working for the British intelligence services might be as damaging as working for the Russians, but, again, nobody minded. Cockburn was known as ‘a decent man’.

When he moved his family to Ireland in 1953 Huston was also pleased to find the Irish had a low opinion of McCarthy. Huston’s house guests included Robert Capa, who made his name as a photographer on the anti-fascist side in the Spanish Civil War, and John Steinbeck, author of Grapes of Wrath, a savage exposure of exploitation in America. Dalton Trumbo, the blacklisted Hollywood writer and one of the Ten, also came to stay. Trumbo, too, had to write under a pseudonym: his uncredited scripts included Roman Holiday, which won, ironically, an Oscar for best screenplay. Bizarrely, and briefly, the Hustons found that Oswald Mosley, the former leader of the British Union of Fascists, lived in the same county, Galway. The well-heeled Mosleys, still on the far right in their politics, spent their winters hunting in Ireland, and their summers in France and Italy.

Loving the pursuits of the Anglo-Irish gentry, especially horses and all to do with them, Huston did not hide his private opinions, including the fact that he was an atheist. The country folk he met, most of them Catholic, still liked him. Their attitude, Huston recalled, was: ‘He’s a good fellow who’s surely going to hell, so why not make things as pleasant as possible for him – temporarily?’

Nevertheless, Ireland was publicly deeply conservative in the 1950s. In 1951, when Huston fell in love with the country, the government capitulated when the Catholic bishops opposed a state healthcare scheme. A victim of ‘McCarthyite smear tactics’, as he put it, Noel Browne, the minister who introduced the reform, was accused of being a communist. Despite this, in the privacy of the polling booth Dubliners re-elected him at the next election. Public defiance of the Catholic Church, on the other hand, was rare.

A football international between Ireland and Yugoslavia in Dublin four years later proved to be an exception. The city’s powerful archbishop, John Charles McQuaid, did not approve of this invitation to a ‘Godless communist’ country, which had imprisoned Cardinal Stepinac for war crimes. Spectators thronged the stadium. Thousands attended who had never gone to a football match before, and probably never would again, ‘unless, of course’, as Cockburn wrote, ‘someone, perhaps an archbishop, tried to get it stopped’.

John Huston eventually left Ireland, not for the US, but Mexico, having picked up an honorary doctorate from Trinity College, Dublin, and, perhaps more significantly, Irish citizenship. Before he died, he made his last film in Ireland, an adaptation of a story by the formerly banned James Joyce, The Dead (1987), featuring his daughter Angelica. Cockburn continued to live in County Cork and remained a mischievous critic of powerful elites, writing under his own name in Punch and Private Eye, and as a columnist in the Irish Times. A review of his autobiography in the New Statesman recommended it to be ‘read and studied by kings and commissars’.

Huston and Cockburn, two Cold War dissidents, stayed the course.

John Mulqueen is the author of ‘An Alien Ideology’: Cold War Perceptions of the Irish Republican Left (Liverpool University Press, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed