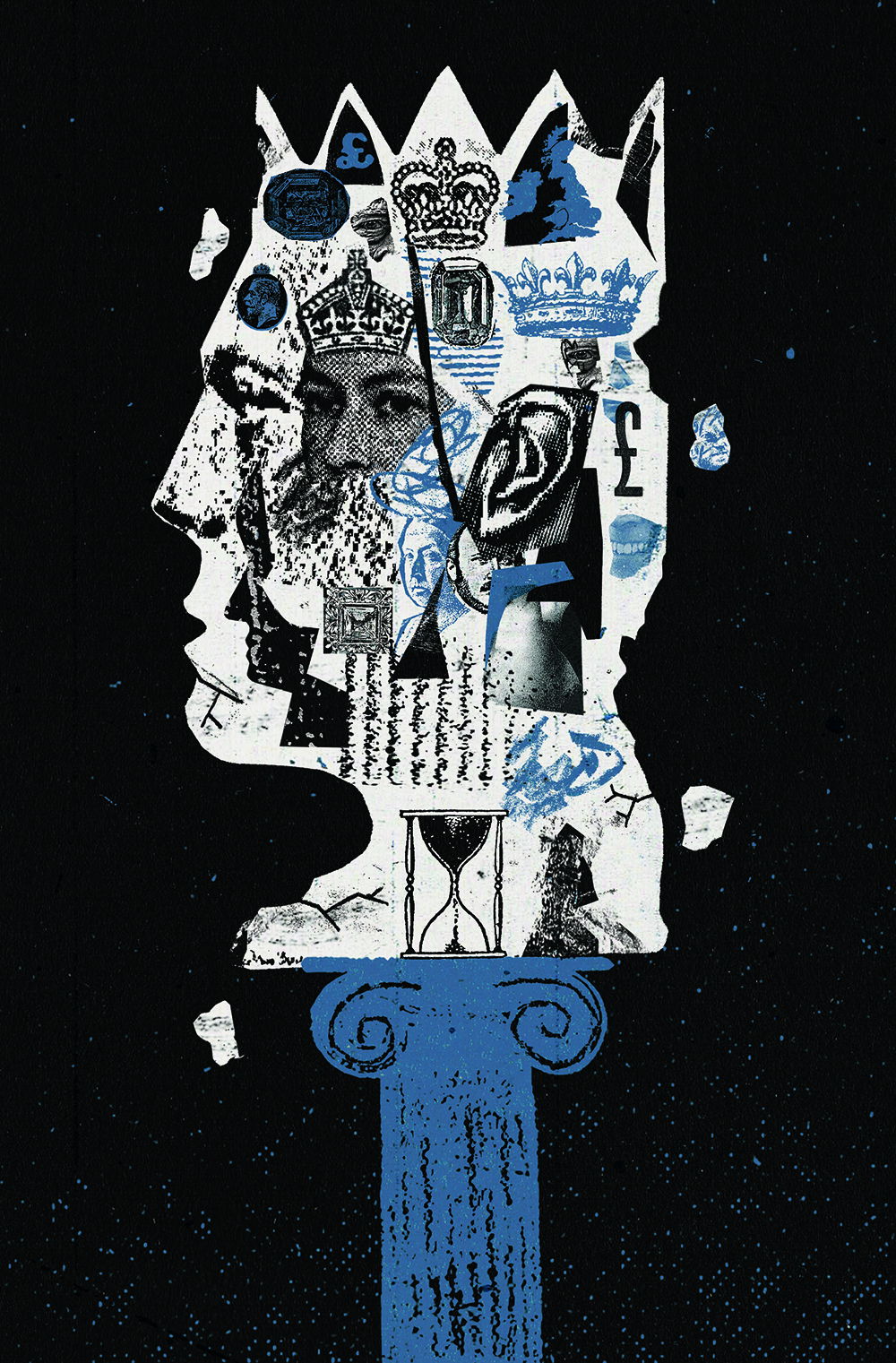

Off with Their Heads! | History Today - 8 minutes read

Recent years have seen a slow but steadily rising tide of dissatisfaction with royalty in Britain. Accelerated by the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the coronation of King Charles III and a regular diet of scandal surrounding Prince Andrew, as well as the fracturing of the tight inner circle of the royal family following the departure of Prince Harry, there are those who now dare to hope for an end to the monarchy.

Opposition to monarchy in Britain is often perceived as a marginal belief that attracts few adherents. Traditionally the monarchy has proved adept at adapting to periods of change and crisis. Criticism of Queen Victoria’s long period of mourning and absence from public duties following the death of Prince Albert in 1861 led to a period of reappraisal that reshaped the appeal of the Crown. After her return to public life, Victoria changed the focus of the monarchy to make it more aligned with middle-class values, public philanthropy and charitable works. Thereafter, a ‘welfare monarchy’ entrenched the values of the royal house at the heart of civil society and proved key to the recovery and success of the public functions of the British Crown. The House of Windsor has followed that course since, most notably in Charles’ attempt to use his coronation to promote support for volunteering.

The tradition of anti-monarchism, however, is as much a feature of British politics as monarchism, and is not, of itself, new. Issues of personal wealth, a narrow and privileged court, impersonal and unrepresentative royal influence and power, and the strong association between monarchy and the values of state, nation and empire have often inspired loathing. For some, like the radical Thomas Paine, hereditary rule was by its very nature immoral, privileging a politics ‘of the blood’ and institutionalising structures of ‘old corruption’ that drew courtiers, the civil service and the executive into an intertwined relationship rooted in power and position. Some monarchs, notably George IV, exemplified this trend and became emblematic of a remote and privileged court characterised by dysfunctional family and marital relations that evoked public scorn and derision.

‘Cost of the Crown’

With its roots in opposition to hereditary rule and recalling the heroes of the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell, anti-monarchism provided a marked strand of radical politics in Britain from the 1790s, through the Chartist movement into the socialist ferment of the 1880s and beyond. More preoccupied with royal misbehaviour, the extravagance of monarchy and sinecures for the favoured than with models of alternative constitutions, anti-monarchism has proved vocal during periods when the integrity of the Crown is in question. Concerns about the expense of royalty, and over the cost of civil list payments from the public purse to support Victoria’s numerous royal offspring when they came of age during her decade-long seclusion, led to a surge of anti-monarchism in Britain in the period 1871-72. The resultant campaign prompted a highly charged public debate about whether the royal family provided value for money. Potently expressed in Sir Charles Dilke’s ‘cost of the Crown’ speech, disquiet with monarchy manifested itself in the formation of radical clubs explicitly devoted to abolition of the monarchy (over 100 of them) and to parliamentary debates about the grants made to the royal children in the House of Commons. At public meetings, tensions boiled over into pitched battles between republicans and loyalists. In Bolton in 1871, William Schofield, a bystander accidentally killed at a protest, became Britain’s first republican martyr since the English Civil War. Here anti-monarchism failed to transcend the placard-waving demonstration and the public gesture of contempt for hereditary rule that has proved a characteristic of recent anti-royal protests.

In the short term, the serious illness of the heir to the throne, Prince Albert Edward (the future Edward VII), and his near death from typhoid in the autumn of 1871, led to a wave of public sympathy for the royal family and a surge of ‘typhoid loyalism’ that revived the position of the Crown. The demonstrations of 1871-72, however, illustrate the degree to which anti-monarchism acted as a barometer for the popularity of the Crown at the height of Queen Victoria’s reign. This remains a point of debate when individual monarchs fall into disfavour with the public. Reliant on public acclamation, the British monarchy has frequently faltered when public opinion turns against it. The recent heavy-handed policing of anti-royal protests at King Charles’ coronation reveals an awareness of the issues that emerge when the Crown falls into disfavour with crowds.

Feeling vulnerable

The monarchy in Britain has never really felt itself in immediate danger of toppling, but has, on occasion, felt the need to bend to the strength of anti-monarchist sentiment. In 1992 the royal household experienced a public backlash when, following a fire at the royal apartments at Windsor Castle, the public was expected to pay for their renovation. Reflecting the royal family’s evasiveness about its tax status, the public mood shifted to one of hostility – after all, it was felt, why should the public pay for these repairs when the monarchy failed to pay its taxes? In the end, the royal family backed down, put its own money into the restoration and made its finances and tax position more transparent. The public demand for the return of the royal family to London to acknowledge the floral tributes to the death of Princess Diana in 1997 constitutes another example of the power and strength of public feeling that tips over into anti-monarchism when the conduct of the royal family disappoints.

In the case of Princess Diana and, more recently, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, younger, approachable royals, depicted as more in touch with the emotions and sentiments of the population, fulfil the role of ‘pretenders’. Able to take on the mantle of outsiders to the royal bloodline, such figures potentially extend the reach of the royal family by proving more representative of the liberalism, pluralism and diversity of modern Britain, but provide a generational rebuke to traditional attitudes among senior royals. Prince Harry revived many traditional anti-monarchist images of a remote, stuffy, out of touch and insidiously inegalitarian (if not actually racist) royal court in his memoir Spare.

It came from abroad

The occasion in the 19th century when the British monarchy felt at its most vulnerable was during the revolutions of 1848, when Chartists organised protests in London and images of falling thrones and tottering monarchies in Europe persuaded Victoria and Albert to leave London and seek refuge in their home on the Isle of Wight. At a time when revolutions in Europe magnified the domestic threat at home, fears that such events might encourage imitators in London fostered an acute sense of anxiety, despite the relatively small scale of protests in the capital. As in 1848, the present-day threat to the monarchy comes most obviously from abroad: in this case from the countries of the Commonwealth of Nations.

If Britain is ever to think the unthinkable about abolishing the monarchy, it will be spurred on by events in the Commonwealth as countries transition to constitutional republics. Barbados has already become a republic, Jamaica has plans in place for a referendum on removing the royal link and there is speculation about another referendum on an elected head of state in Australia following the election of Anthony Albanese’s Labor government in May 2022. In the Caribbean, memories of slavery and the monarchy’s part in it have proved potent at turning indifference to the Crown into anti-monarchism, if not outright republicanism. The treatment of Meghan Markle has had a powerful impact there in reinforcing negative memories of royalty, and its links with racism.

‘Regime change’?

The monarchy in Britain has never really felt itself in immediate danger of falling. Monarchies fell, or royal families abandoned their thrones in Europe, after periods of civil war, revolution, or financial and political crisis – notably the French Revolution of 1789, the European revolutions of 1848 or during the political turmoil following the end of the First World War. Regime change in Britain would require a similar period of profound crisis. Scottish independence and the backwash from Brexit might plant the seeds for a possible break-up of the UK under a lacklustre kingship by Charles III, but, as during other periods of crisis in Britain, people tend to look to the monarchy as a symbol of continuity.

Much hinges on whether Charles can reproduce his mother’s feat of representing all four nations. His stated aim of slimming down the size and cost of the royal household and reducing the active members of the royal family to its core might be sufficient to blunt some anti-monarchist sentiment. Nevertheless, the sensitive issues surrounding finance, personal wealth, a narrow and privileged court, immorality and dysfunctional family relationships haven’t changed as a criticism of the Crown, but, perhaps, the context has. Against the background of a cost of living crisis, these issues have become magnified and there is consistent polling evidence that shows less enthusiasm for the monarchy among the young than among older voters, at a time when the outline of the ‘New Carolean’ period remains stubbornly blurred.

Antony Taylor is Professor of Modern British History at Sheffield Hallam University and the author of ‘Down with the Crown’: British Anti-monarchism and Debates about Royalty since 1790 (Reaktion, 1999).

Source: History Today Feed