The Bruneri-Canella Case - 9 minutes read

On 9 February 1927, Giulia Canella opened the morning edition of La Domenica del Corriere to discover that her dead husband had come back to life. She could hardly believe her eyes. Eleven years earlier, on 25 November 1916, Captain Giulio Canella had been leading an attack on Monastir (modern Bitola), when his company came under heavy fire. When the survivors crawled back to their positions, Canella wasn’t there. Some thought they had seen him being taken prisoner after being wounded; under questioning, enemy prisoners later denied having captured him. The most obvious explanation was that he had been killed. Yet when the town was retaken, his body couldn’t be found. The Ministry of War recorded him as simply ‘missing in action’ – and for the next 11 years, nothing more was heard of him.

Nothing, that is, until La Domenica del Corriere broke the story of an unknown man interned in the mental hospital at Collegno. The man had been arrested in March 1926, after being caught trying to steal an urn from the Jewish cemetery in Turin. Clearly very agitated, he was unable to tell the police his name – and had nothing on him to give them any clue. On 2 April, the local court confined him to the mental hospital.

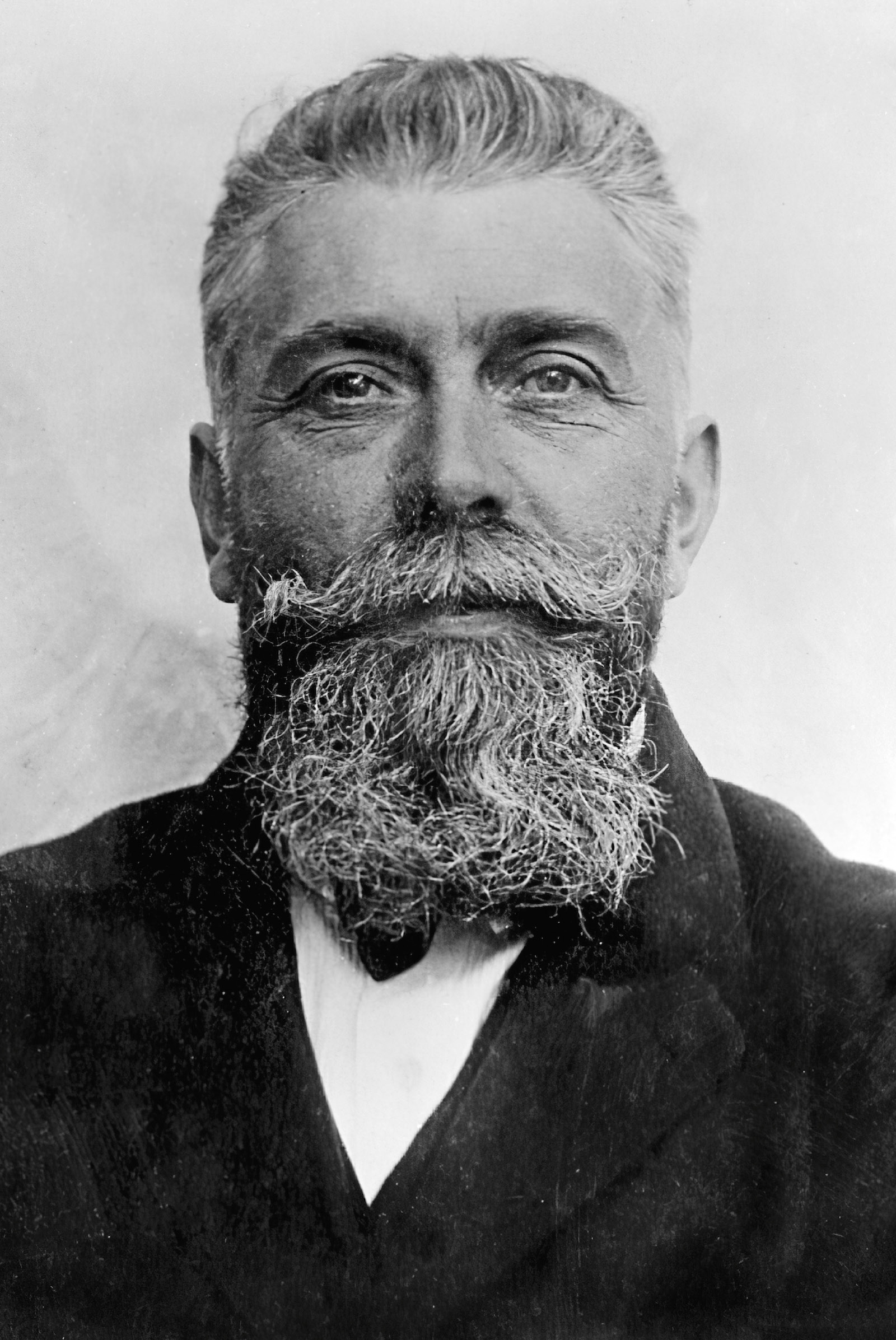

He was, by all accounts, a ‘distinguished’ figure. As the journalist Ugo Pavia later reported, he bore a striking resemblance to Tsar Nicholas II. Around 40-45 years old, he was calm and courteous, spoke good Italian and gave every impression of being well educated. But he had no memory whatsoever of his past, his country of origin or his profession. His doctors reasoned that he was suffering from amnesia, brought on by trauma, and opted to publicise his case in the hope of identifying him.

Giulia Canella recognised her husband immediately. Everything about the ‘smemorato di Collegno’ (‘amnesiac of Collegno’) tallied with what she remembered about him. Born on 5 December 1882, he would then have been a little over 44 years old. Before being called up for military service, he had been a headteacher in Verona; and together with Fr. Agostino Gemelli had founded the Rivista di filosofia neo-scolastica – a leading journal of Catholic philosophy. Most tellingly, he looked similar, too. He had the same distinguished appearance, the same ‘imperial’ beard, the same smiling eyes. The man in the article, she concluded, appeared identical to her lost husband.

Hastily, Giulia wrote to the hospital and, on 27 February 1927, she was allowed to visit. According to one report, she first saw him through a peephole, whereupon she exclaimed: ‘God, how old he’s grown!’ She was then introduced to him. Dressed in the same clothes she had worn for 11 years, Giulia was led down a corridor, just as he was walking in the other direction. Falling to her knees, she gave a cry of recognition: ‘It’s him, it’s him!’

That settled it. Although the police had their doubts, Giulia was adamant. On 2 March, ‘Prof. Canella’ was released and returned home to Verona, amid much media fanfare.

Mistaken identity?

The joy was short-lived, however. Just days later, the Questura of Turin received an anonymous letter, laiming that the smemorato was actually Mario Bruneri – a local typist who had been arrested several times ‘for fraud and identity theft’. Also in his early forties, he had not been seen since abandoning his family for a Brescian prostitute six years earlier and was wanted for a string of crimes committed elsewhere. This was enough to convince the police chief to summon ‘Prof. Canella’ back to Turin. Two days later, Bruneri’s family identified him. Not wanting to leave anything to chance, the police chief also had his fingerprints taken and sent off to be compared with Bruneri’s file at the Advanced School of Police in Rome. This had already been done when the smemorato had first been arrested, but no match had been found. Now it was a different matter. Quick as a flash, the authorities wired back that the smemorato was certainly Bruneri.

Now that his real identity had apparently been confirmed, Bruneri – as we should now call him – was sent back to the hospital. There, he was examined by the neurologist, Alfredo Coppola. After a careful investigation, Coppola concluded that, although Bruneri seemed to exhibit some symptoms of amnesia, ‘none [stood] up to scrutiny’.

Since Bruneri was apparently sane, he was immediately placed under arrest until he could be tried for his previous crimes. But this was where the real drama began. Although his identity seemed clear enough to the police, nothing had yet been proved. Legally speaking, he was still unknown. This rendered his arrest invalid, forcing the authorities to release him. The Bruneri family was outraged. Not wanting him to wriggle out of trouble yet again, they appealed the decision and on 5 November 1928 the Court of Appeal in Turin ruled that the smemorato was indeed Bruneri.

Rather than being the end of the matter, this sparked a legal battle that would run for almost 20 years. Bruneri was adamant that he was Canella. On 24 March 1930, the Corte di Cassazione in Rome overturned the Court of Appeal’s decision, on the grounds that it had denied Bruneri the chance to present evidence in his defence. Not to be outdone, the Bruneri family fought back. The following year, the Court of Appeal in Florence reviewed the case again. This time, a host of new evidence was produced. Canella’s old colleague, Fr. Gemelli, was called to testify; photographs were used to compare Bruneri and Canella’s physiognomies; and fresh fingerprint analysis was presented. By the narrowest of margins, the judges upheld Bruneri’s identification and decreed that the case was now closed.

‘The Tramp’

Bruneri was hauled off to prison to serve the remaining two years of his sentence. Yet even now, he refused to give up. After the Second World War, he asked to have the whole business reopened, claiming, implausibly, that he had been the victim of fascist repression. His request was turned down, however – and that, legally speaking, was the end of it.

But what had happened to Giulio Canella? And why did Bruneri choose to steal his identity? A possible clue was provided by ‘Signora Taylor’, an Englishwoman living in Milan. Sometime later, she claimed that, in 1923, she had come across a homeless soldier. Impressed by his courtesy, she helped him and the two quickly struck up a friendship. Over coffee, he intimated that he had fought in the First World War but could not remember much about his previous life.

As time went on, however, ‘the Tramp’ – as Taylor dubbed him – began to behave strangely. One day, he was charming and urbane; the next, coarse and vulgar. He forgot things he had told her or retold stories in different ways. To her mind, there was only one explanation: ‘the Tramp’ was actually two people, each virtually identical to the other. The first was probably Giulio Canella; the second, Bruneri. Most likely, she reasoned, Bruneri had met Canella on the streets and, noticing their similarity, befriended him, with the intention of stealing his identity and thereby evading the police.

But there are problems with this. How would Bruneri have known that it was worth stealing the amnesiac Canella’s identity? And why did he try to assume Canella’s identity by getting himself arrested? If he was trying to throw off his criminal past, it would have been an enormous – not to say unnecessary – risk. Although Taylor’s ‘Tramp’ may have been Bruneri, there is no evidence that either of them ever met Canella. What became of the professor is anyone’s guess.

‘Gut feeling’

It was a curious case, much like that of Martin Guerre, almost 400 years before; but what made it so significant were the means used to expose Bruneri. Throughout the trials, the question of the smemorato’s identity was treated as a litmus test for forensic science. The evidence caused a sensation in the press; yet – much to the police’s surprise – it met with hostility, even ridicule, in the courts. Fingerprint analysis should have been the least controversial. Since being used to identify a murderer in Argentina back in 1892, it had regularly been used in Italian courts. Yet because the School of Police had offered two different conclusions on being presented with the same prints, judges dismissed the technique as too subjective. It was the same with the psychological reports. Coppola’s conclusions were contradicted by the hospital doctors, who had detected no signs of malingering. Even physiological comparisons were attacked. Medical records were unreliable and unless photographs of Canella and Bruneri were taken from the same angle, in the same light, it proved impossible to identify any meaningful differences. Instead, each of the cases was decided almost entirely based on unsubstantiated witness testimony – in effect, ‘gut feeling’. Yet it was precisely because forensic science was so heavily criticised that the case proved to be such a turning point in Italian legal history. It forced researchers to refine their techniques, paving the way for forensic science to become one of the pillars of Italian legal practice.

What made the case even more extraordinary was the attitude of Giulia Canella. Throughout the trials, she stood by the man she took to be her husband. Between 1928 and 1931, they had three (more?) children together; after his release they moved to Brazil, where she vehemently defended him against his detractors. The question is: did she really believe that Bruneri was her husband? Or did she only want him to be?

As Martha Hanna has noted, the Great War made widows of at least two million women, including around 200,000 in Italy. Alone, they had to ‘confront the challenges of single-parenthood, the oppressive burdens of grief and economic insecurity’. Even if Giulia did have her doubts, her determination to ‘recognise’ and defend her ‘husband’ was understandable, even natural – and is emblematic not just of the wounds the First World War inflicted, but of the scars it left, even decades later.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, is now available in paperback.

Source: History Today Feed