A Modern Martyr | History Today - 5 minutes read

Seventy-five years ago, with the Allied victory in Europe merely a month away, a German pastor was led to the scaffold. As far back as February 1933, when many observers saw little threat in the new chancellor, he was one of the earliest to denounce Hitler. Off and on for the next 12 years, Dietrich Bonhoeffer would resist the Nazis: first through sermons and support for Jews, then as a clerical diplomat and double agent. He was a scion of the Prussian nobility and a German patriot; but when his name was called on 9 April 1945 at Flossenbürg concentration camp, he was hanged as a traitor.

The co-founder of Amnesty International called Bonhoeffer the ‘archetypal prisoner of conscience’. Yet, unlike the great martyrs of the 20th century, unlike Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Bonhoeffer achieved little. Whereas Gandhi steered India to independence and King led the push for civil rights, Bonhoeffer left no tangible legacy. Nonetheless, his courage should make him their equal.

Born in 1906, Bonhoeffer grew up in an august family. His father was the pre-eminent psychiatrist in Germany and his grandfather and great aunt both served the royal court, as chaplain and lady-in-waiting respectively. A sight-reading pianist, he shocked his upper-class relatives with his youthful declaration that he wanted to be a theologian.

Despite earning two doctorates and studying under key figures in the German school of liberal Protestantism, crucial to Bonhoeffer’s formation was his year in New York. He studied at Union Theological College, but became increasingly disaffected by its concessions to secularisation. ‘They preach about virtually everything, except the gospel of Jesus Christ’, he wrote. It was 1931, and with nearby Harlem still in the midst of a creative renaissance, Bonhoeffer found his spiritual home in the black community of its Abyssinian Baptist Church.

Bonhoeffer was ordained in Berlin later that year and began lecturing at the university. His return coincided with the rise of the Nazis and, informed by his experience of segregation in the US, Bonhoeffer was quick to spot Hitler’s menace. The day after Hitler took power in 1933, he broadcast a speech on the radio denouncing Nazi morality. In time, he would help coordinate Jews’ safe passage out of the Reich.

With war imminent, Bonhoeffer returned to New York in June 1939. But after a month, his conscience drew him back to Germany. Shortly after Hitler’s invasion of Poland that autumn, he began collaborating with the Resistance. His circle of plotters comprised people much like him: brave, cultured and patriotic. In contrast to the quiet life of study and prayer he had envisaged, he now had to spin myriad webs of deception.

Having been barred from serving as an army chaplain, and with the prospect of being called to the front, in 1940 Bonhoeffer was recruited by the Abwehr – German military intelligence. His role had been organised by well-placed friends who combined a job in the top brass with support for the Resistance.

Saved from the draft, Bonhoeffer wrote theology (focusing on the nature of discipleship and the role of the Church in a secular world) and lived the daily life of a Lutheran minister. But his pastoral duties were his cover story for Abwehr work, which was itself a front for his anti-Nazi efforts.

The Abwehr’s anti-Hitler leaders explained Bonhoeffer’s appointment on the grounds of his international experience. His stints in the US and Britain (he had spent a year and a half in London after his radio broadcast in 1933) and his contacts in Allied countries made him suited to analyse the morale of the societies Hitler sought to obliterate.

Instead, Bonhoeffer tried to gauge and then garner Allied support for Germany’s home-grown anti-Nazis. Bishop George Bell of Chichester, an old mentor from his time in London, tried to persuade the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden that Bonhoeffer was worth supporting. Eden responded: ‘I see no reason whatsoever to encourage this pestilent priest.’

The Gestapo came for Bonhoeffer at his home in April 1943, gleefully rounding up a cleric working for the rival intelligence agency. Bonhoeffer would spend the next two years, his final ones, in prison.

The initial charge against him was money-laundering (from aiding refugees fleeing the Reich) and it was only after the attempted assassination of Hitler on 20 July 1944 that the Gestapo discovered a paper trail tracing major conspiracies to the Abwehr. Bonhoeffer was clearly implicated.

When news of the plot’s failure reached Winston Churchill, the prime minster dismissed the Resistance. It was merely evidence, he said, of ‘the highest personalities in the German Reich murdering each other’. Churchill was right that many of the plot’s architects were complicit in Hitler’s rise to power, but Bonhoeffer – the conspirators’ ethicist – was an exception.

With Hitler vowing absolute vengeance against traitors, Bonhoeffer’s chances of release collapsed. Fearing reprisals against his family, he declined a guard’s offer to help him escape Berlin’s Tegel prison. Even then, there were times when fortune might have saved him, such as when the van taking him and captured foreign agents to Flossenbürg broke down. Just two weeks after his death on 9 April 1945, Flossenbürg was liberated by the Americans.

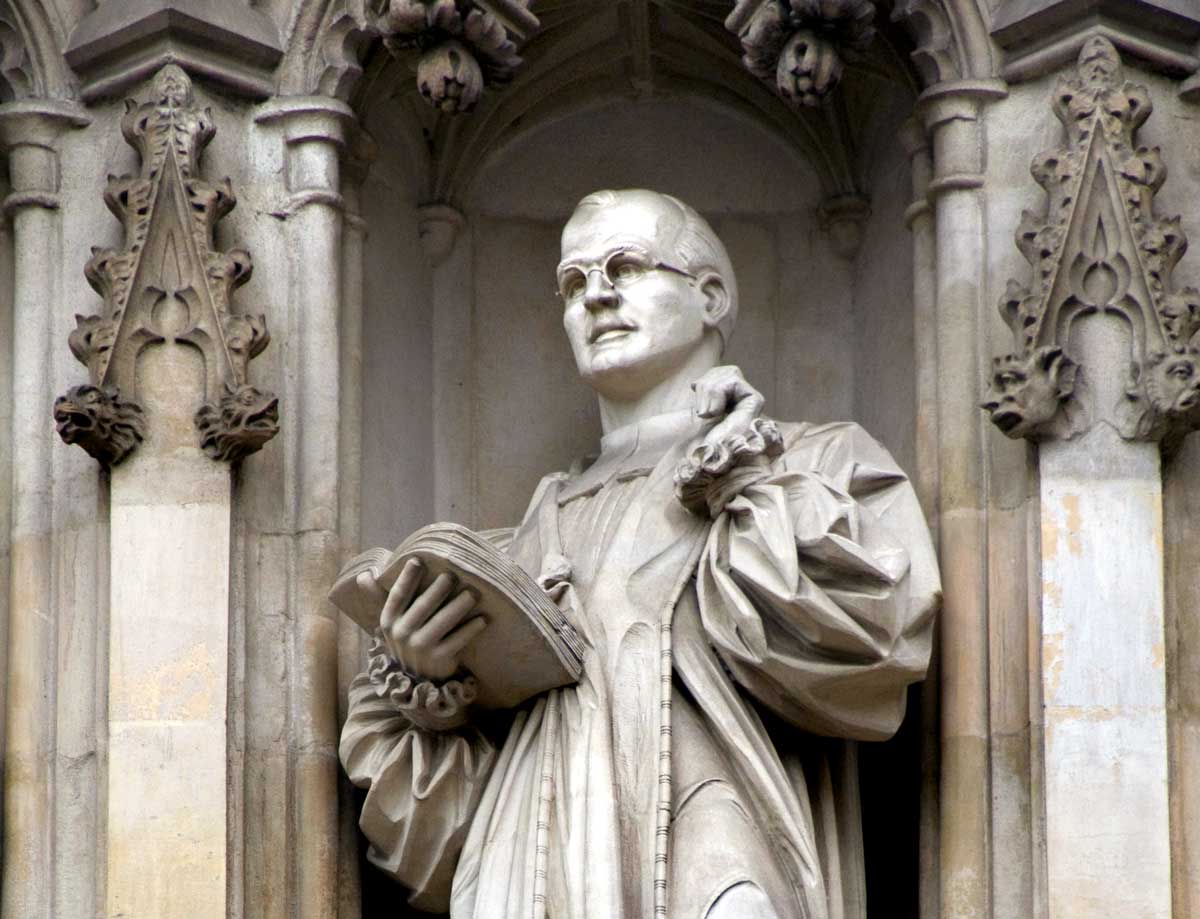

Visitors to the west entrance of Westminster Abbey today can see Bonhoeffer’s statue among the ‘modern martyrs’, two places from Martin Luther King. Although he did not affect the course of history, as King did, Bonhoeffer is symbolic. He is a reminder to question Manichaean stereotypes of the Second World War. Bonhoeffer’s story is the epitome of Germany during the Third Reich. It tells how a figure and a country steeped in culture had its existence upended and ravaged, then destroyed.

Daniel Rey is the author of ‘Checkmate or Top Trumps: Cuba’s Geopolitical Game of the Century’, runner-up in the 2017 Bodley Head & Financial Times essay prize.

Source: History Today Feed