Beyond Good and Evil | History Today - 17 minutes read

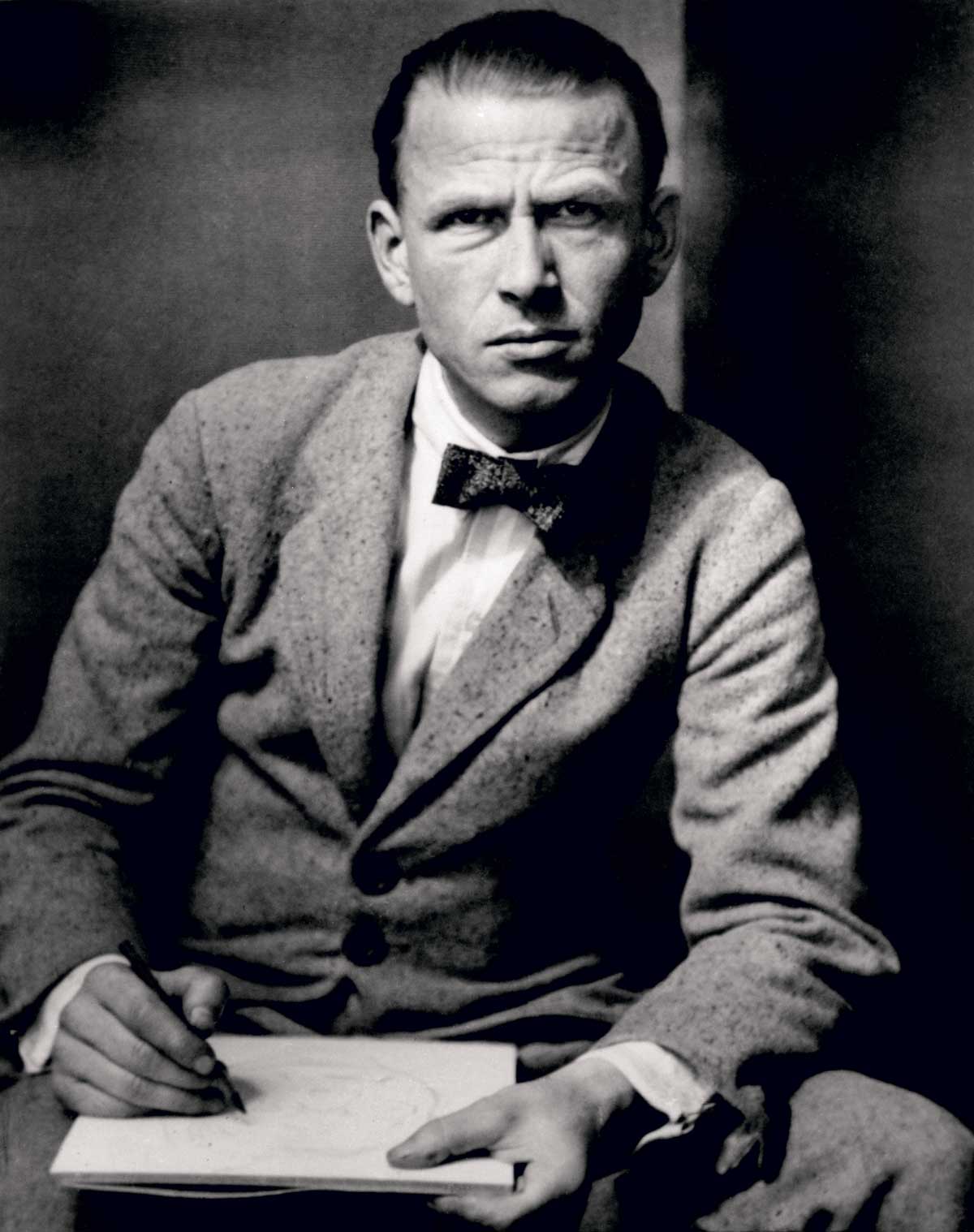

It was not the front, but the journey to the front that was the worst: ‘There was some shit in people’s pants, I tell you.’ Two years into the war, Otto Dix had seen it all. In 1914 he had signed up enthusiastically to the field artillery. Back then, people had assumed that victory would be swift in coming, but that hope had been disappointed. A great gash of trenches had come to score the western front. Neither side could force a decisive breakthrough. Now, on the slopes above the river Somme, the British and the French armies were making a concerted effort to smash a hole through the labyrinth of German trenches. All summer the battle had been raging. Dix, approaching the Somme, had been deafened by artillery fire of a volume he had never imagined possible and seen the western horizon lit as though by lightning. Everywhere was ruin: mud and blasted trees and rubble. In his dreams Dix was always crawling through shattered houses and doorways that barely permitted him to pass. Once he had arrived at his post, though, his fear left him. Stationed with a heavy machine-gun battery, he felt mingled excitement and calm. He even found time to paint.

Back in Dresden, the famously beautiful city in Saxony where he had been an art student, Dix had experimented with a range of styles. Only 23 when war broke out, and from an impoverished background, the sense of urgency he felt as a painter was that of a man determined to make a name for himself. By night, as Dix huddled beside a carbide lamp with his oils or his pens, flares over no-man’s land would light up corpses grotesquely twisted on barbed-wire entanglements. Then, every morning, dawn would illumine a cratered landscape of death. On 1 July, the opening day of the battle, almost 20,000 British soldiers had been mown down as they sought in vain to take the enemy trenches and another 40,000 left wounded. A fortnight later, every yard of the German lines had been pounded by shells. New ways of killing were being developed. On 15 September, monstrous machines called, by their British inventors, ‘tanks’ grumbled and ground their way for the first time across the battlefield. By the end of the month, flying machines were dropping bombs on the trenches below. Only in late November did the fighting grind to a halt. By that stage, casualties numbered a million. To Dix, hunkered behind his machine gun, the world was transformed. ‘Humanity’, he wrote, ‘changes in demonic fashion.’

On the side of the angels

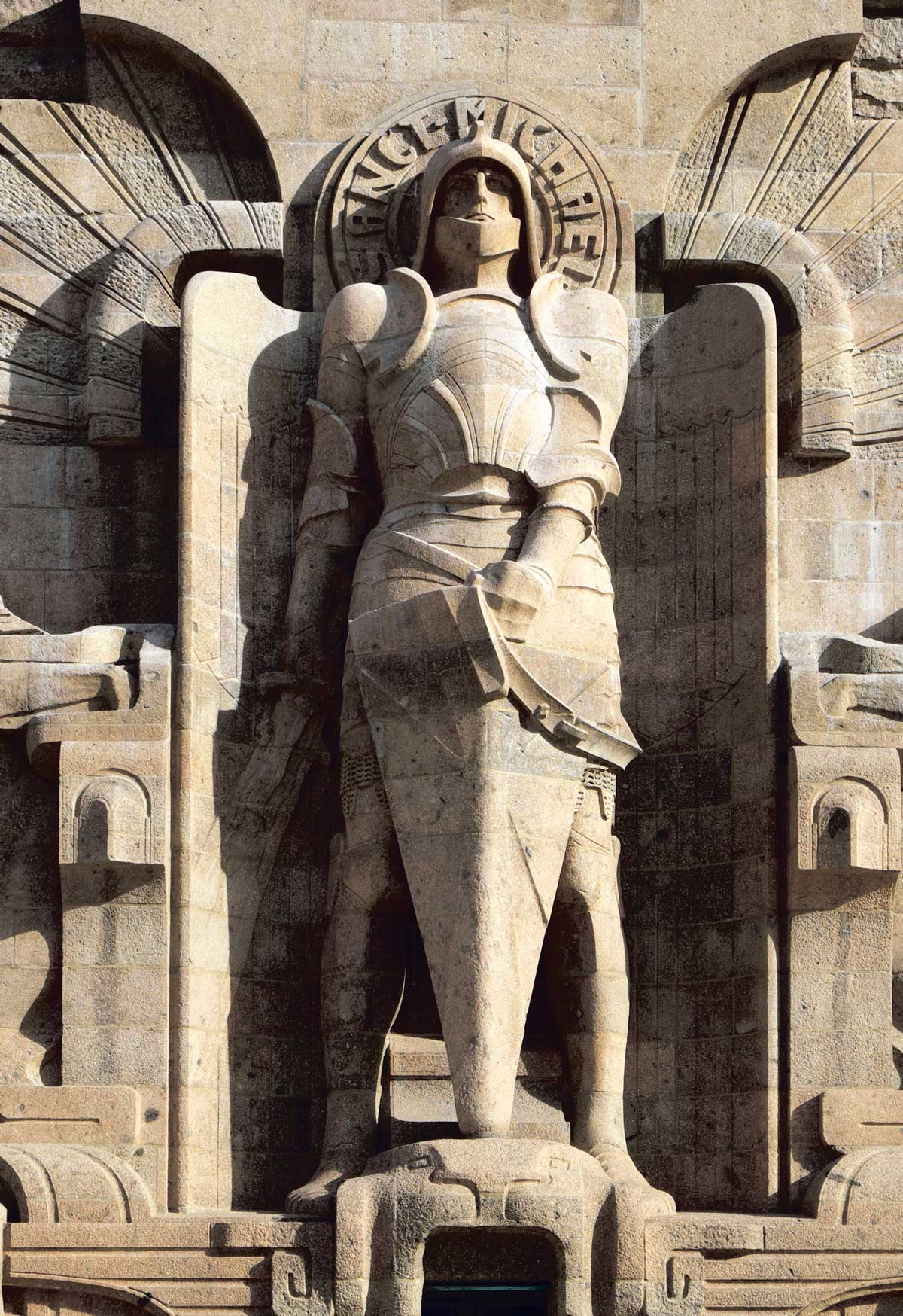

There were plenty, though, who thought themselves on the side of the angels. Back in Saxony, a year before the outbreak of war, a vast monument had been unveiled to mark the centenary of a bloody victory over Napoleon. The centrepiece of the Völkerschlachtdenkmal was a colossal statue of St Michael, winged and armed with a fiery sword. That Germany’s struggle against its foes mirrored the cosmic war of angel against demon was a conviction that reached to the top. The Kaiser, as the war dragged on and a naval blockade of Germany began to bite, grew ever more convinced that the British were in league with the devil. Patriotic Britons, for their part, had been saying much the same about Germany. Bishops joined with newspaper editors in hammering the message home. The Germans had succumbed to ‘a brutal and ruthless military paganism’. They had returned to the worship of Woden. In Germany, The Times announced, ‘Christianity is beginning to be regarded as a worn-out creed.’

It was easier, perhaps, for armchair warriors to believe this than for soldiers on the front. Behind the British lines at the Somme, in the small town of Albert, there stood a basilica topped by a golden statue of the Virgin and Child. A year previously, the spire had been hit by a shell. The statue had been left hanging precariously, as though by a miracle. Rumours began to spread in both the German and British trenches that whichever side brought it down was destined to lose the war. Yet many, when they looked up at the Virgin, were inspired to dwell not on the calculus of victory and defeat but on the suffering of both sides in the battle. ‘The figure once stood triumphant on the cathedral tower’, wrote one British soldier; ‘now it is bowed as by the last extremity of grief.’ The Virgin, too, had known what it was to mourn a son. Amid the misery and suffering that had become the common experience across the whole of Europe, the image of Christ tortured to death on a cross took on for many a new potency. Both sides sought to turn this to their advantage. In Germany, pastors compared the blockade enforced by the Royal Navy to the nails with which Christ had been fixed to the cross; in Britain, stories of German soldiers crucifying a Canadian prisoner had long been a staple of propaganda. Even so, in the trenches themselves, where soldiers – if they did not find themselves trapped on barbed wire, or riddled by machine gun-fire, or disembowelled by an exploding shell – would live day after day in the valley of the shadow of death, the Crucifixion had a more haunting resonance. Christ was their fellow-sufferer. On the battlefield of the Somme, soldiers would note in wonder their survival amid all the devastation of wayside crucifixes – chipped and pockmarked with bullets though they were. Even Protestants, even atheists, were capable of being moved. Christ was imagined sharing in a jest passed along the trenches, standing beside soldiers in their pain and weakness. ‘We have no doubts, we know that You are here.’

A kind of Golgotha

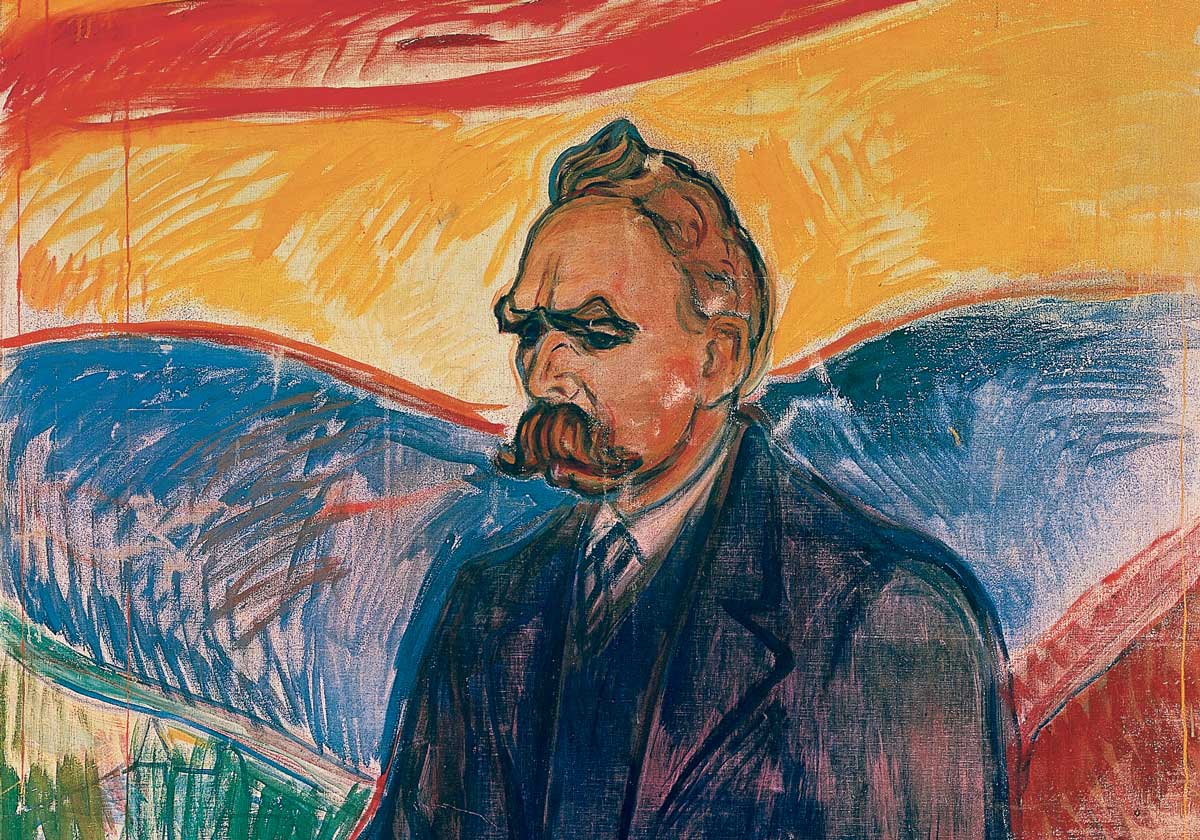

Dix, too, in his dugout, had Christ’s sufferings on his mind. Raised a Lutheran, he had brought a Bible with him to the Somme. In the course of his service on the front, he had seen enough artillery attacks to recognise in their invariable aftermath a kind of Golgotha. With his artist’s eye, he could glimpse in the spectacle of a soldier impaled on a shard of metal something of the Crucifixion. Yet Dix, to a degree that would have confirmed British propagandists in all their darkest suspicions of the German character, scorned to see Christ’s suffering as having served any purpose. To imagine that it might have done so was to cling to the values of a slave. ‘To be crucified, to experience the deepest abyss of life’: this was its own reward. Dix, volunteering in 1914, had done so out of a desire to know the ultimate extremes of life and death: to feel what it was to stick a bayonet in an enemy’s guts and to twist it around; to have a comrade fall over suddenly, a bullet square between his eyes; ‘the hunger, the fleas, the mud’. Only in the intoxication of such experiences could a man be more than a man: an Übermensch. To be free was to be great; and to be great was to be terrible. It was not the Bible which had brought Dix to this conviction. Alongside him in his dugout he had a second book. So stirred was he by its philosophy that in 1912, while still an art student in Dresden, he had made a life-size plaster bust of its author. Not just his first sculpture, it had also been his first work to be bought by a gallery. Discerning critics, inspecting the bust’s drooping moustache, its thrusting neck, its gaze shadowed by bristling eyebrows, had proclaimed it the very image of Friedrich Nietzsche.

God is dead

‘Do we not hear the noise of the grave-diggers who are burying God? Do we not smell the divine putrefaction? – for even gods putrefy! God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.’ To read these words beside the Somme, amid a landscape turned to mud and ash, littered with the mangled bodies of men, was to shiver before the possibility that there might not be, after all, any redemption in sacrifice. Nietzsche had written them back in 1882: the parable of a madman who one bright morning lit a lantern and ran to the market-place, where no one among his listeners would believe his news that God had bled to death beneath their knives. Little in Nietzsche’s upbringing seemed to have prefigured such blasphemy. The son of a Lutheran pastor, his background had been one of pious provincialism. Precocious and brilliant, he had obtained a professorship at the age of 24; but then, only a decade later, had resigned it to become a shabbily genteel bum. Setting the seal on the sense of a squandered career, he had suffered a mental breakdown. For the last 11 years of his life, he had been confined to a succession of clinics. Few, when he died in 1900, had read the books written in an escalating frenzy of production. Posthumously his fame had grown with startling rapidity. By 1914, when Dix marched to war with his writings in his knapsack, Nietzsche’s name had become one of the most controversial in Europe. Condemned by many as the most dangerous thinker who had ever lived, there were others who hailed him as a prophet. There were many who considered him both.

The retreating tide

No one had dared to gaze so unblinkingly at what the murder of its god might mean for a civilisation. ‘When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet.’ Nietzsche’s loathing for those who imagined otherwise was intense. Philosophers he scorned as ‘secret priests’. Socialists, communists, democrats: all were equally deluded. ‘Naiveté: as if morality could survive when the God who sanctions it is missing!’ Enthusiasts for the Enlightenment, self-proclaimed rationalists who imagined that men and women possessed inherent rights, Nietzsche regarded with contempt. It was not from reason that their doctrine of human dignity derived, but rather from the very faith which they believed themselves – in their conceit – to have banished. Proclamations of rights were nothing but flotsam and jetsam left behind by the retreating tide of Christianity: bleached and stranded relics. God was dead – but in the great cave that once had been Christendom his shadow still fell. For centuries, perhaps, it would linger. Christianity had reigned for two millennia. It could not easily be banished. Its myths would long endure. And yet they were no less myths, for all that, because they now wore the show of the secular. ‘Such phantoms as the dignity of man,the dignity of labour’: these were Christian through and through.

Nietzsche did not mean this as a compliment. It was not just as frauds that he despised those who clung to Christian morality, even as their knives were dripping with the blood of God; he loathed them as well for believing in it. Concern for the lowly, far from serving the cause of justice, was a form of poison. Nietzsche had penetrated to the heart of everything that was most shocking about the Christian faith. ‘To devise something which could even approach the seductive, intoxicating, anaesthetising, and corrupting power of that symbol of the “holy cross”, that horrific paradox of the “crucified God”, that mystery of an inconceivably ultimate, most extreme cruelty and self-crucifixion undertaken for the salvation of mankind? ’. Like St Paul, Nietzsche knew it to be a scandal. Unlike Paul, he found it repellent. The spectacle of Christ being tortured to death had served the powerful as bait. It had persuaded them – the strong and the healthy, the beautiful and the brave, the powerful and the self-assured – that it was their natural inferiors, the hungry and the humble, who deserved to inherit the earth. ‘Helping and caring for others, being of use to others, constantly excites a sense of power.’ Charity, in Christendom, had become a means to dominate. Yet Christianity, by taking the side of everything ill-constituted, weak and feeble, had made humanity sick. Its ideals of compassion and equality before God were bred, not of love, but of hatred: a hatred of the deepest and most sublime order, one which had transformed the very character of morality, a hatred the like of which had never before been seen on earth. This was the revolution that Paul – ‘that hate-obsessed false-coiner’ – had set in motion. The weak had conquered the strong; the slaves had vanquished their masters.

‘Ruined by cunning, secret, invisible, anaemic vampires! Not conquered – only sucked dry! ... Covert revengefulness, petty envy become master!’ Nietzsche, when he mourned the taming of antiquity’s beasts of prey, did so with the passion of a scholar who had devoted his life to the study of their civilisation. He admired the Greeks, not despite, but because of their cruelty. So scornful was he of any notion of ancient Greece as a land of sunny rationalism that large numbers of students, by the end of his tenure as a professor, had been shocked into abandoning his classes. Nietzsche valued the ancients for the pleasure they had taken in inflicting suffering; for knowing that punishment might be festive; for demonstrating that, ‘in the days before mankind grew ashamed of its cruelty, before pessimists existed, life on earth was more cheerful than it is now’. That Nietzsche himself was a short-sighted invalid prone to violent migraines had done nothing to inhibit his admiration for the aristocracies of antiquity and their heedlessness towards the sick and the weak. A society focused on the feeble enfeebled itself. This is what had made Christianity such a malevolent bloodsucker. If it was the taming of the Romans that Nietzsche mourned, then he regretted as well how they had battened onto other nations. Nietzsche, whose contempt for the Germans was exceeded only by his scorn for the English, was so little an enthusiast for nationalism that he had renounced his Prussian citizenship when he was only 24 and died stateless. Yet, for all that, he had always lamented the fate of his forebears. Once, the forests had sheltered Saxons who, in their ferocity and their hunger for everything that was richest and most intense in life, had been predators no less glorious than lions: ‘blond beasts’. But then the missionaries had arrived. The blond beast had been tempted into a monastery. ‘There he now lay, sick, wretched, malevolent toward himself; filled with hatred of the vital drives, filled with suspicion towards all that was still strong and happy. In short, a “Christian”.’ Dix, enduring the extremes of the western front, did not have to be a worshipper of Woden to feel that he was free at last.

Between beast and Übermensch

‘Even war’, he recorded in his notebook, ‘must be regarded as a natural occurrence.’ That it was an abyss, across which, like a rope, a man might be suspended, fastened between beast and Übermensch: here was a philosophy that Dix felt no cause to abandon at the Somme. Yet it could seem a bleak one, for all that. Soldiers, amid the corpses and the mud, rarely cared to imagine with Nietzsche that there might be no truth, no value, no meaning in itself – and that only by acknowledging this would a man cease to be a slave. The scale of the violence that had convulsed Europe did not shock most of its peoples into atheism. On the contrary, it served to confirm them in their faith. How otherwise to make sense of the horror? The fabric that lay between earth and heaven could appear eerily thin. As the war ground on and 1916 turned to 1917, so the end times seemed to be drawing close. In Portugal, in the village of Fatima, the Virgin made repeated appearances, until at last, before huge crowds, the sun danced, as though in fulfilment of the prophecy recorded in Revelation, that a wondrous sign would appear in heaven: ‘a woman clothed with the sun’. In Palestine, the British won a crushing victory at Armageddon and took Jerusalem from the Turks. In London, the foreign secretary issued a declaration supporting the establishment of a Jewish homeland, a development many Christians believed was bound to herald the return of Christ.

Yet he did not come back. Nor did the world end. In 1918, when the German high command launched a massive attempt to smash their opponents once and for all, the operation they had codenamed ‘Michael’, in honour of the archangel, peaked and broke and ebbed. Eight months later, the war was over. Germany sued for terms. The Kaiser abdicated. A squalid peace was brought to a shattered continent. Dix returned from the front. In Dresden, he painted maimed officers, malnourished infants and haggard prostitutes. He saw beggars everywhere. On street corners there were gangs of agitators. Some were communists, others nationalists. Some wandered barefoot, prophesying the end of the world and calling for man to be born again. Dix ignored them all. Asked to join a political party, he would answer that he would rather go to a brothel. He continued to read Nietzsche.

The heaviest blow

‘He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.’ Nietzsche had warned that confusions were bound to follow from the death of God. Good and evil would become relative. Moral codes would drift unanchored. Terrible violence would be perpetrated. In 1933 a regime came to power in Germany that regarded Christianity with the contempt of a Nietzsche. Hitler, who in 1928 had publicly proclaimed how Christian his movement was, condemned it in private as ‘the heaviest blow that ever struck humanity’. Its concern for the weak he viewed as cowardly and shameful. It had resulted in any number of excrescences: alcoholics breeding promiscuously while upstanding national comrades struggled to put food on the table for their families; mental patients enjoying clean sheets while healthy children were obliged to sleep three or four to a bed; cripples having money and attention lavished on them that should be devoted to the fit. Idiocies such as these were precisely what National Socialism existed to terminate. The churches had had their day. The new order, if it were to endure, would require a new order of man: the Übermenschen.

Even committed Nietzscheans might flinch before their discovery of what this meant in practice. Dix was revolted by the Nazis and they in turn dismissed him as degenerate. Sacked from his teaching post in Dresden, forbidden to exhibit his paintings, he turned to the Bible and, in 1939, painted the destruction of Sodom. Fire consumed a city that was unmistakably Dresden. The image proved prophetic. When, that same year, Hitler’s ambitions plunged Europe into war, cities across the continent burned: Warsaw, Rotterdam, London. Then, as the tide turned against Germany, ruin was visited on the Reich itself. In July 1943 – in an operation codenamed Gomorrah – a sea of fire engulfed Hamburg. In February 1945, it was the turn of Dresden. The most beautiful cityscape in Germany was reduced to ashes. Three months later the war in Europe was over. The Übermenschen was no more.

‘After a terrible earthquake’, Nietzsche had written, ‘a tremendous reflection, with new questions.’ Dix, who had been conscripted into the Wehrmacht during the dying days of the war, was released from a French POW camp in 1946 and returned to what remained of Dresden. There, he painted himself as Christ, portrayed against a backdrop of barbed wire. The image of the Crucifixion increasingly haunted his paintings. By the end of his life, he was painting religious scenes that had no hint of allegory, no echo of the present day.

Dix never did portray Nietzsche again.

Tom Holland’s latest book is Dominion: the Making of the Western Mind (Little, Brown, 2019).