Statues, Politics and The Past - 8 minutes read

What purpose do statues serve? This question came to the fore when former prime minister Theresa May announced plans in June 2019 for a memorial in London’s Waterloo station commemorating the arrival to Britain in 1948 of the first of the Windrush generation. The Windrush Foundation criticised the plans, pointing out that the government had not consulted members of the Caribbean community in the UK before publicising them.

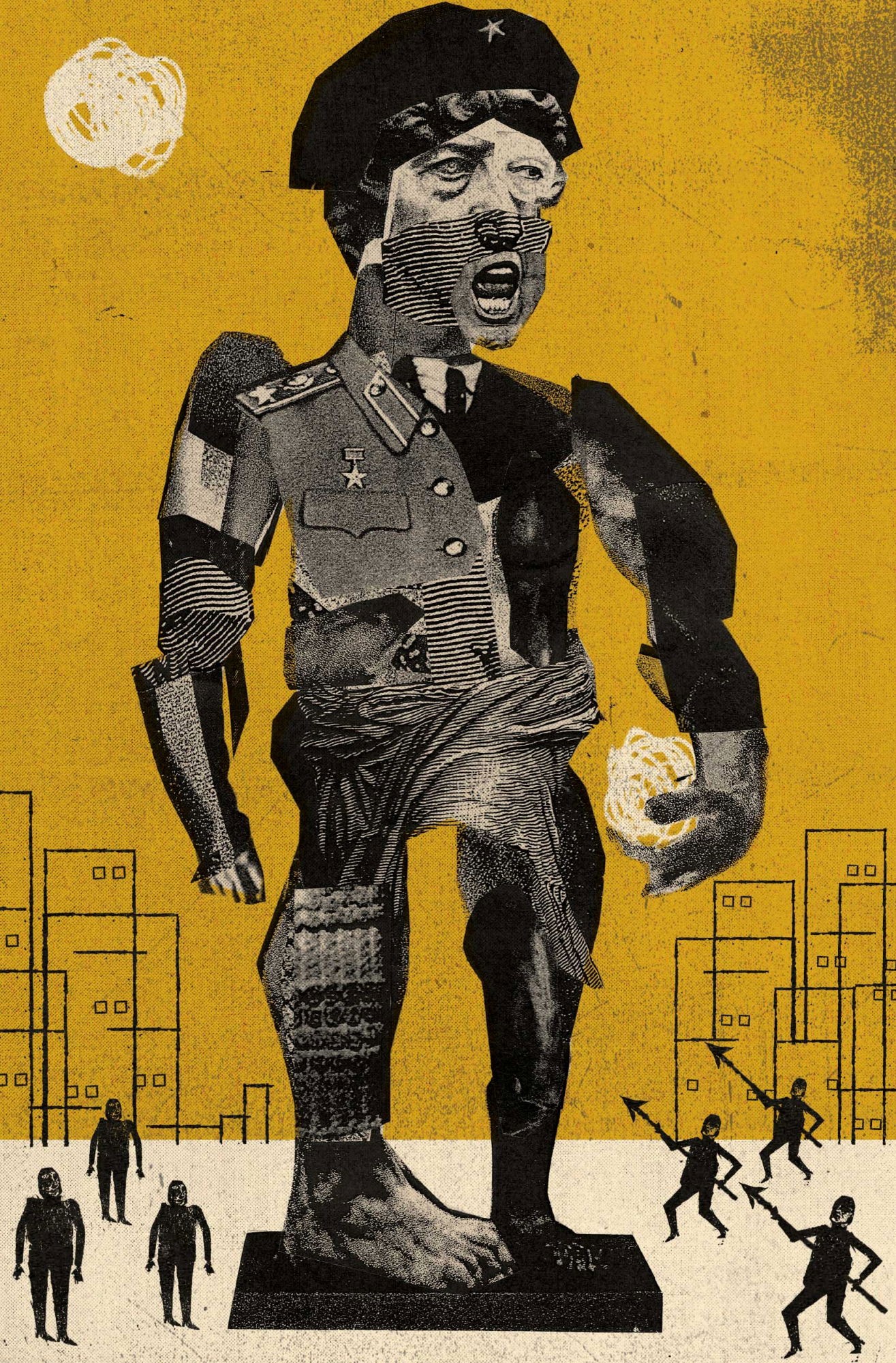

This was merely the latest in a succession of recent episodes that have fuelled global debates over the purpose of public monuments in society. The ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ movement, which began at the University of Cape Town in 2015 and then spread to Oxford University the following year, protested against statues of the colonialist Cecil Rhodes on both universities’ campuses. Moreover, the past few years have seen ongoing campaigns in the US to have Civil War statues commemorating Confederate figures removed from public spaces. Counter-campaigners have sought to maintain those statues as they are. What these episodes all have in common is that, within each, monuments have become lightning rods for wider conflicts between competing visions of history.

Controversial monuments

Nations and communities have various options for dealing with controversial monuments. One is to remove them entirely. In some contexts, authorities have done precisely this. With the fall of Hitler’s Germany, for example, Nazi monuments throughout the former Reich were hastily pulled down, part of a wider effort to exorcise the spectre of National Socialism.

Some who oppose particular monuments do not wish to take them down entirely, however, asserting that simply removing a statue is tantamount to pretending a traumatic event in the past never happened. Rather, they advocate removing controversial statues while retaining their pedestals as a reminder of the events that they invoke. Accordingly, empty plinths throughout the US show that some communities have confronted their difficult pasts in this way.

Proponents of retaining controversial monuments have suggested that to remove them would be to efface a part of history. They argue that statues should be preserved because they teach people about the past. But is viewing a statue actually an effective way of learning about history?

Statuomania

An insightful way of answering this question is to examine the attitudes of past societies to their public monuments. Developments in 19th-century Europe, in particular, have the potential to unlock a fresh vantage point onto this contemporary issue. In that era, many political communities pursued state-building programmes that involved appropriating history to serve interests in the present. Nations devoted substantial energy and resources to commemorating heroes from the past in monumental form. Helke Rausch’s important work on the political uses of statues in European capitals between 1848 and 1914 shows that major cities received dozens of new monuments: Paris gained 78 new statues, Berlin 59 and London 61. With good reason, historians often characterise the 19th century as an age of ‘statuomania’.

These monuments continue to shape the fabric of European cities. The gilded bronze statue of Joan of Arc installed in Paris’ Place des Pyramides in 1874, for example, remains a familiar sight in the French capital. Every summer, Joan greets the Tour de France as its riders circle the city’s historic heart during the final stage of the race. The statue of Richard I erected outside London’s Palace of Westminster in 1860 still stands proudly outside the home of Parliament. Richard’s unyielding bronze gaze has watched over defining events in the past 150 years. The fate of the grand statue of Frederick the Great erected on Berlin’s Unter den Linden in 1839 has been intertwined with the history of the city. During the Second World War, the monument was encased in protective cement. Beginning in 1950, the DDR authorities relocated it several times. It was only after the reunification of Germany in 1990 that Frederick was returned to his original 1839 location.

Belgian nationhood

The ways in which monuments were used in 19th-century Belgium aptly illustrate wider European trends and attitudes in that era. Belgium was founded through revolution in 1830-1 and its political elite spent the next few decades consolidating its newly won independence. As part of a multifaceted programme intended to forge a new national identity, political authorities drew extensively from the past with the aim of legitimating Belgian nationhood in the present. In contrast to more venerable nations such as England and France, Belgian state-builders could not point to continuity through long-standing institutions and structures that had existed for centuries. Instead, they had to harness the legitimating power of history in a different way. As a result, the ideas and aspirations which shaped their efforts came into focus more clearly than in other states.

Elite project

Seeking to use the past to stimulate feelings of communal solidarity, Belgian political elites commissioned – and provided substantial levels of funding for – scores of new monuments for Brussels, the capital, and other cities and towns throughout the nation. Many of these new monuments honoured figures who lived long before the Belgian Revolution. Some evoked the Middle Ages, while others – such as the statue of the Gallic chief Ambiorix unveiled in Tongeren in 1866 – channelled the even more distant past. In a decree issued on 7 January 1835, the Belgian government signalled its intention to carry out ‘a national task’ by sponsoring the creation of new statues ‘to honour the memory of the Belgians who had contributed to the glory of their country’. In the years that followed, a diverse array of figures including Charlemagne, Peter Paul Rubens and Andreas Vesalius were immortalised in bronze and stone in public spaces throughout the nation, presented as exemplary Belgians from earlier ages.

This wave of Belgian statuomania was not just about conveying an interpretation of the past. It was one element of a programme intended to mediate the relationship between the past and the present. In 1859, Brussels witnessed the inauguration of a monumental column honouring the members of the National Congress, the legislative assembly set up during the Belgian Revolution in 1830. An account written the following year in praise of Brussels’ Congress Column had this to say about Belgium’s statuary:

The history of every people is written in its monuments. They reveal, without diminishment or partiality, their mores, their beliefs, their institutions. This observation is true for all eras and applicable to all countries, and is particularly confirmed in Belgium.

This rather self-conscious effort to assert that Belgian monuments were impartial serves to confirm that precisely the opposite was the case. The statues created in 19th-century Belgium do not simply convey neutral, incontrovertible information about the past. Rather, they present a particular view of history, one which had it that while Belgian nationhood had only become a political reality in 1830-1, it had been an impulse that had shaped the hearts and minds of the inhabitants of the region for centuries. Those who visited the capital in the middle years of the 19th century were able to see a tangible version of this history, cast in bronze and carved in stone. Together, Brussels’ 19th-century monuments constitute a kind of open-air pantheon, aligning statues to heroes from the past, such as Vesalius, with memorials of the Belgian Revolution, including the Congress Column.

Negotiating the past

The statues created in Belgium advance the interpretation of history that prevailed in the mid-19th century. Later developments, including the rise of Flemish nationalism and a backlash against colonial activities in the Congo, prompted the emergence of new and sometimes conflicting concepts of the nation’s past. In turn, attitudes towards the nation’s statuary and the values they embody have evolved. Yet practically all the statues erected in the nation in the decades following 1830-1 still stand. They continue to embody the contingent political circumstances in which they were created: the defining years in which Belgium worked to secure its independence.

So, how can the statuomania of the 19th century inform debates today? Statues can teach us about history, but they do not convey some immutable truth from the past. Instead, they are symbolic of the fixed ideas of a specific community regarding its past, as captured at a particular point in time. As our case study of 19th-century Belgium demonstrates, history is complex and susceptible to refashioning in line with changing political aspirations. In a way, statues do tell us about the past, but that is not to say that we should accept what they tell us uncritically.

Conflicts over particular statues are the result of specific disagreements over an aspect of history. The sharp divides between those who would see Rhodes or a Confederate general as a villain and those who would see each as a hero are cases in point.

Disputes have also been caused by people interpreting monuments in different ways. On the one hand are those who regard them as embodying some essential and imperishable historical certainty. On the other are observers who are able – and willing – to look beyond a particular statue to a more complex and contestable past reality. The latter are better poised to recognise that outmoded and divisive political values embodied in any monument belong in one place and one place alone: the past.

Simon John is Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at Swansea University.