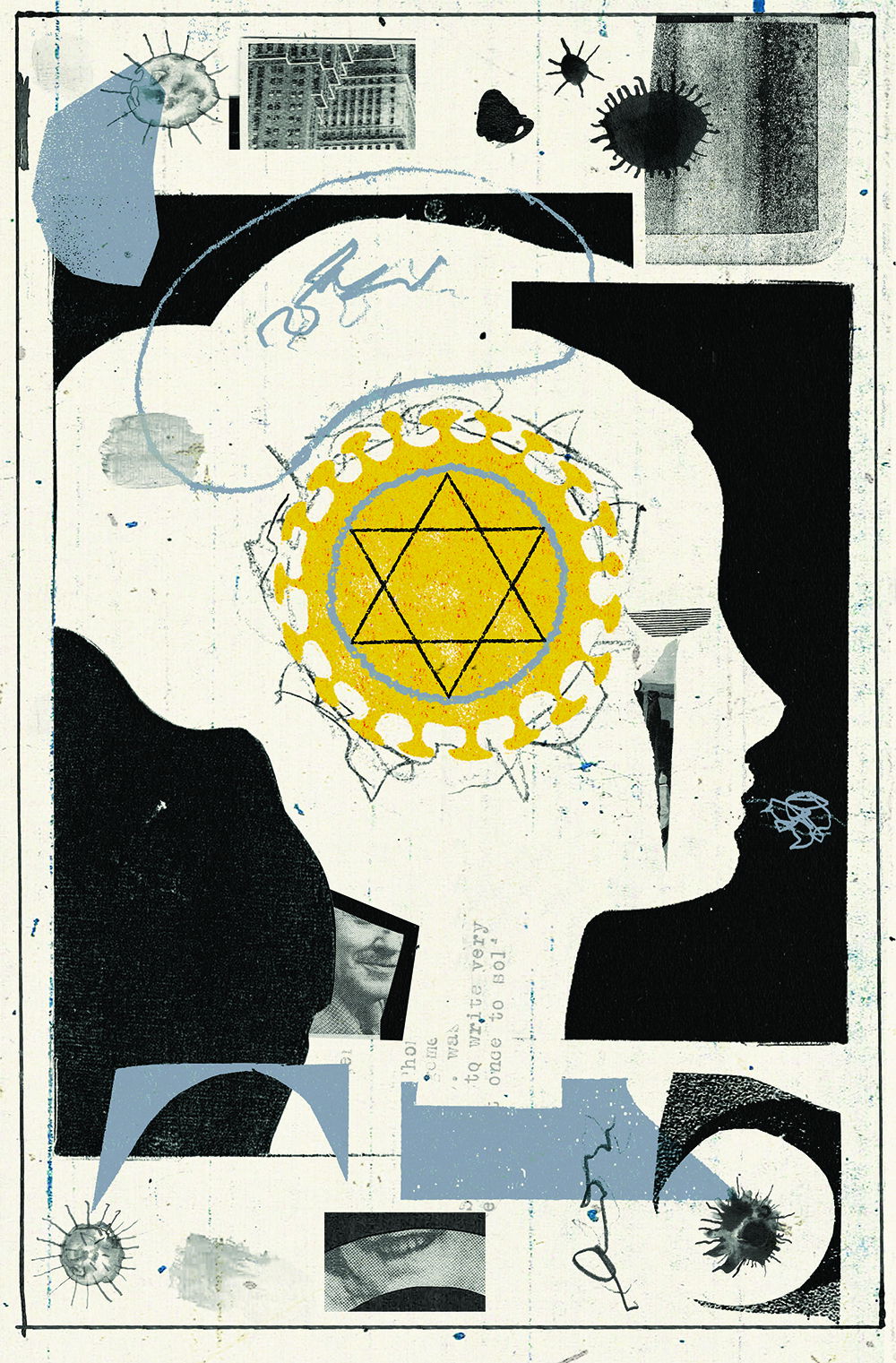

Germany and the Yellow Star - 8 minutes read

During the Covid pandemic, as those opposed to lockdowns and vaccinations organised large protests, several German cities reacted with alarm. Some protesters had taken to wearing a yellow star – the symbol first forced upon Jews by the Nazis in September 1941 – as a sign of their own perceived victimhood. Deemed a trivialisation of the Holocaust and a threat to public order, Munich banned the symbol in May 2020, prompting Felix Klein, the Federal Government Commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight against Antisemitism, to insist on further bans. Frankfurt followed suit in March 2022.

Anne Frank

It seems particularly inappropriate for German descendants of the Nazi generation to be identifying with its Jewish victims. Comparing Covid policies with Nazi antisemitism is absurd. But this did not prevent some protesters from developing another inappropriate point of comparison between their situation and the Holocaust. For some, the time stuck at home in lockdown was comparable with the situation of Anne Frank, hidden in an annexe in Amsterdam before she was deported to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen and there murdered. In Germany, one case above all triggered indignant responses. At a demonstration in Karlsruhe in November 2020, an 11-year-old girl stood on a podium and declared that she had had to celebrate her birthday secretly with her friends as otherwise she might have been denounced by her neighbours: ‘I felt as Anne Frank must have done when she had to be as quiet as a mouse if she didn’t want to be caught.’

This demonstration, like many Covid protest rallies in Germany, had been organised by the so-called ‘Querdenker’ or ‘lateral thinking’ movement. The Querdenker is a motley congregation of contrarians opposed to government measures with links to the far right. Its founder, Michael Ballweg, was arrested in 2022 following charges of, among other things, money laundering. There was more than a little suspicion that the child had been manipulated by the Querdenker for their own anti-lockdown campaign. In response to her comments, the state prosecutor in Karlsruhe opened an investigation but soon came to the conclusion that there was no legal case to answer. The girl was too young to be prosecuted. Felix Klein made clear several times that he regarded comparisons with Anne Frank or the wearing of the yellow star as forms of ‘secondary antisemitism’.

Trivialisation

The German legal authorities have, in the past, raised charges in similar cases. Following a number of antisemitic incidents in the late 1950s – which culminated in the desecration of a synagogue in Cologne – the West German authorities revised Article 130 of the criminal code to make it a criminal offence to agitate against groups on the basis of their nationality, ethnicity or religion. During the pandemic, there were calls for this article to be revised yet again. The problem was that while Article 130 clearly criminalised the denial or trivialisation of the Holocaust, it was less clear when it came to National Socialism more generally: while glorifying or justifying the Nazi regime was explicitly specified as a criminal act, trivialisation was not. Were those who wore yellow stars at protests specifically trivialising the Holocaust? Given that the Nazis introduced the Jewish badge in 1941 as a measure to facilitate not just the segregation but ultimately the deportation and murder of Jews, it would seem reasonable to assume so, but it was not certain. Add to this the clause in Article 130 stipulating that any punishable offence would need to be committed in a manner which endangered public order, and it is clear that the criminal code did not offer the unambiguous definition required to take action against Covid protesters.

Article 130 was eventually revised in late 2022, but not because of this conundrum. It was amended following a complaint from the EU Commission that Germany had not adequately criminalised certain forms of racism, especially regarding denial and trivialisation. But this appears to have referred to genocides and xenophobia other than the Holocaust and antisemitism. The new law still makes no reference to it being a criminal offence to trivialise National Socialism.

What’s gone wrong?

One might object that resorting to police and judicial measures is heavy-handed. Are protesters wearing yellow stars really setting out to trivialise the Holocaust? Certainly that is the effect. But the protesters were trying to draw attention to their perceived persecution by equating it to that of a group whose suffering is universally acknowledged. They were seeking to validate their interpretation of their own experience, rather than downgrade that of the Jews; by overlooking the dangers of trivialisation, however, they undermined their cause.

Particularly concerning is the real possibility that many protesters simply had no idea how crass the comparisons were. Consider another case that hit the headlines, that of ‘Jana from Kassel’. Jana stood on a podium at a Querdenker demonstration in Hanover on 21 November 2020 and compared her campaign against Covid restrictions to Sophie Scholl, probably the most famous member of the anti-Nazi White Rose Movement, who was arrested and executed in 1943:

Yes, hello, I am Jana from Kassel and I feel like Sophie Scholl because I have actively been in resistance now for months, giving speeches, attending demonstrations, distributing leaflets … I am 22 years old, just like Sophie before she was killed by the Nazis.

Her short speech was brought to an abrupt end by a member of the security team who was not prepared to put up with such ‘nonsense’. When the security guard told her she was trivialising the Holocaust, Jana could not understand what she had done wrong and burst into tears. A video of the speech went viral. Germany’s Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas, wrote on Twitter:

Whoever today compares themselves with Sophie Scholl or Anne Frank is making a mockery of the courage required to confront the Nazis. Such comparisons render the Holocaust harmless and exhibit an intolerable forgetting of history.

What, we might ask, has gone wrong with Holocaust education, or education about National Socialism more generally, if protesters against anything and everything draw equivalences between their own situations and the fate of the Jews and others under Nazism?

Comparison points

Felix Klein is always quick to point to problematic comparisons with the Holocaust, and in the last two to three years, debates have been raging in Germany over whether Nazi antisemitism can, or should, be compared with colonialism. Germany faces a double bind: the Holocaust is understood to have been unique, but it is regularly remembered by evoking the mantra ‘nie wieder’ – ‘never again’. Quite how today’s Germans are supposed to ward off the danger of recurrence when, by definition, the unique can never recur remains an unanswered question. Jana’s comparison was unseemly, but perhaps the bigger issue is that she has not been taught what an appropriate comparison might be. It is quite possible that in Germany few really know what an appropriate comparison would be.

The other problem highlighted by Covid protests in Germany is that memory of the Holocaust is often shaped more by identification with the victims than with an awareness of perpetration: responsibility for (supposed) perpetration was pushed onto the current government, which stood accused of implementing measures (lockdown, masks, vaccination) comparable in their supposed repressiveness to the Third Reich. Yet Germans are, as the artist Moshtari Hilal and the political geographer Sinthujan Varatharajah recently put it, ‘people with a Nazi background’. Most Germans do not stand in a lineage linking them with German Jews. Here again is a double bind: Germans are expected to empathise with Jewish victims of the Holocaust, while seeing themselves in relation to the perpetrators. Empathy, of course, does not mean identification, but, in practice, separating these two responses is not easy, any more than it is easy to explore legacies of perpetration without wanting to find excuses and apologies for the involvement of family members. For all that Germany has done to uncover and present, in exhibitions around the country, the history of perpetration and ‘bystanderism’ during the Third Reich, many Germans struggle to find meaningful ways to connect their own lives, at several generational removes, with this history. It is simply easier to feel sorry for oneself by ‘snuggling up’, so to speak, to the victims.

Recommended reading

I recently received a book for review, Bas von Benda-Beckmann’s After the Annex: Anne Frank, Auschwitz and Beyond, published in German in 2021 and, originally, Dutch in 2020. In the book, von Benda-Beckmann, a researcher at the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, takes up the story of what happened to those who had been hidden in the Prinsengracht after Anne’s diary ends. It can be recommended to those who compared themselves to Anne Frank during the pandemic. Most of us emerged from lockdown alive and well – which was, after all, the purpose of it. By contrast, following his liberation from Auschwitz in January 1945, Anne’s father Otto went in search of those with whom he had been in hiding, only to discover they had all been killed. The contrast could not be greater.

Bill Niven is Emeritus Professor in Contemporary German History at Nottingham Trent University.

Source: History Today Feed