The King Who Wasn't There - 14 minutes read

Early in 1145, worried about the growing threat of Muslim forces intent on reconquering Crusader territory in the Holy Land, Bishop Hugh of Jabala travelled west. In a desperate appeal for Christian aid, Hugh sought to enlist the help of Pope Eugenius III. A meeting between the bishop and the pontiff took place on 18 November that year. During it, Bishop Hugh told the pope that one ‘Prester John, king and priest of a land in the extreme Orient, a Christian and a descendant of the Magi who are mentioned in the Gospel, and rules over the same people they governed … was proposing to go to Jerusalem and help the crusaders’.

Much to the dismay of Europe’s Christians, Prester John and his army did not materialise to assist the Crusaders in their fight. One reason Hugh gave for this, as a contemporary recorded, was that, approaching from the east, Prester John’s forces were unable to cross the Tigris and so turned to the north, where the water sometimes froze in the winter cold. John reportedly waited there for some years, but, on account of the continued mild weather and after losing much of his army because of the unaccustomed climate, he was forced to return home. Another, more substantive, reason for Prester John’s absence was that he did not exist. He was a fantasy: a construct, entirely of European creation.

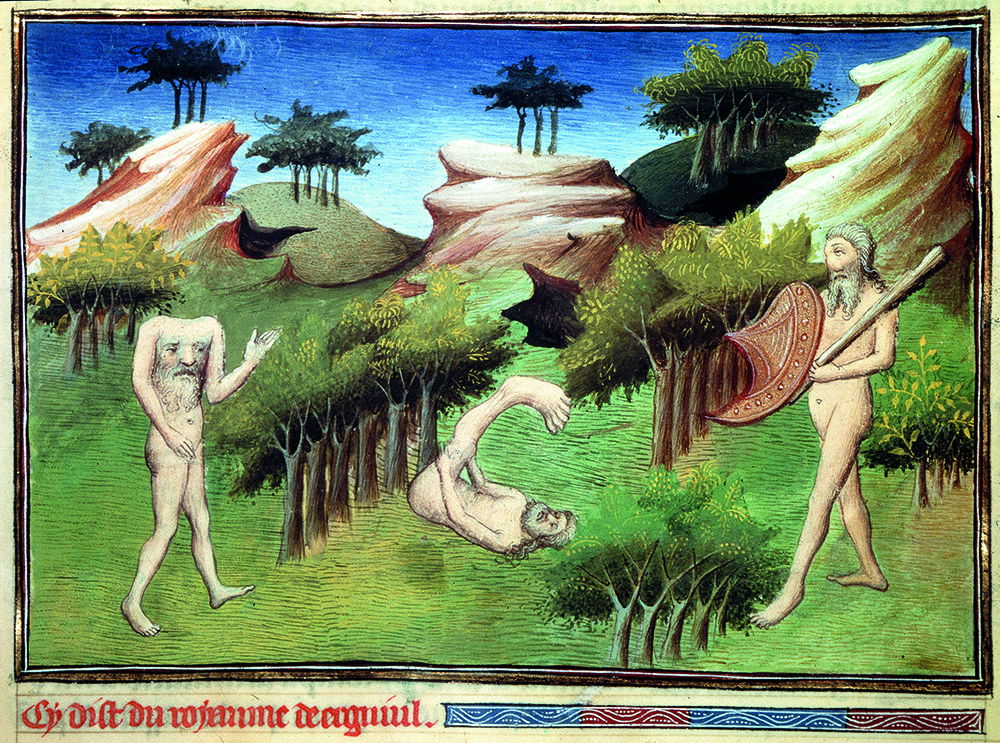

Despite this, from approximately 1165, letters claiming to be from Prester John began to circulate throughout Europe. They endorsed and built upon Bishop Hugh’s claim, declaring that John possessed the richest and most powerful kingdom on Earth. This was a place, the letters suggested, full of vast quantities of gold, jewels and spices, and brimming with miraculous features: crystal clear rivers of emeralds flowing from Paradise, the fountain of youth and even, at the edge of the kingdom, the Garden of Eden. In Prester John’s lands, it was reported that you could encounter phoenixes, giants, dog-headed men, one-eyed men and every incarnation of mythical creature that even the most creative medieval imagination could conjure.

With all of this in mind it is no surprise that throughout every echelon of medieval society, these letters created a frenzy. No one could say where they had come from or what messengers had carried them to Europe, but copies were everywhere. In addition to the more than 100 manuscripts in Latin which survive today, these letters were also translated into English, German, French, Russian, Serbian and Hebrew. And it was through the widespread transmission of these letters in these vernacular languages that the Prester John legend took hold and flourished in every corner of medieval Europe.

Origin story

For those who became aware of Prester John, the first question they sought an answer to – in a similar vein to El Dorado, Atlantis and King Solomon’s mines – was: ‘Where are this famous king and country to be found?’ The search for the realm of Prester John consequently became one of the great enterprises of the medieval and early modern period.

Pope Alexander III was the first pioneer of this quest. In 1177, the papal physician Filippo, armed with diplomatic letters (copies of which still survive in the libraries of Cambridge and Paris), was sent in search of Prester John. Little is known of where Filippo travelled or what became of his mission, as nothing was heard from him again. But regardless of this unfortunate outcome, the European appetite to find this mythical ruler was not quelled. Marco Polo, Vasco da Gama and Christopher Columbus all set out in search of John. Some of them even claimed to have found him, each time renewing the Prester’s enduring relevance in European culture.

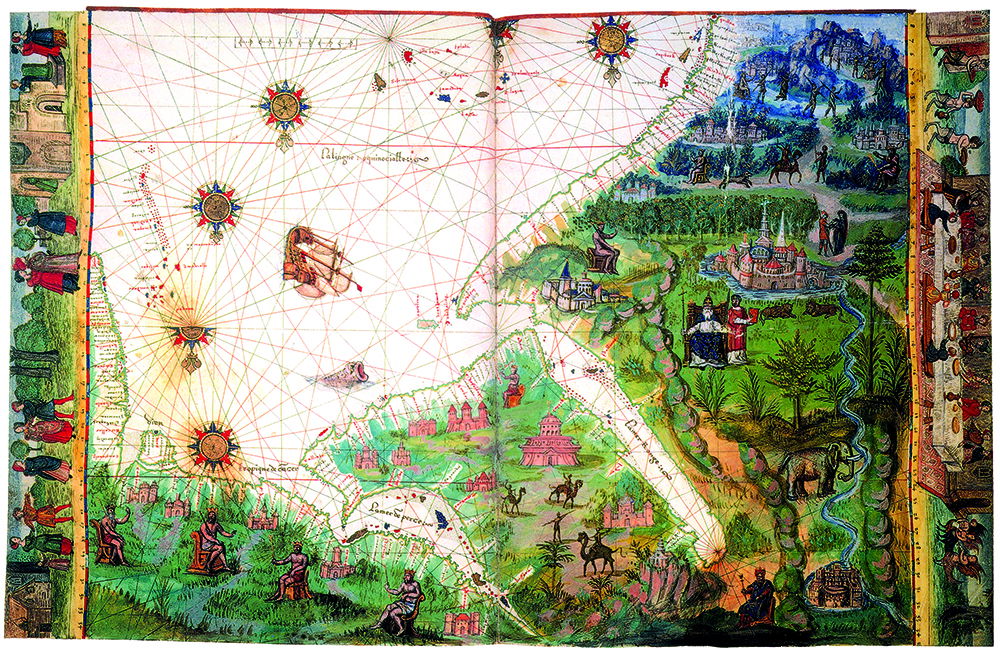

Over the centuries, merchants, adventurers and scholars chased Prester John across the globe. As such, from the 12th to the 17th century, cartographers placed him varyingly (and sometimes simultaneously) in central Asia, India, China and Ethiopia. His appearance on world maps further reinforced the belief that somehow, somewhere, beyond the horizon, there truly existed a Christian priest-king waiting to be found. Cartographers were compelled to portray Prester John on their maps because they believed him to be real, and they believed him to be real because he was portrayed on their maps. But as time passed and the fog of geographical obscurity disappeared, so too did Prester John. And as this once perceived reality gave way to what is an irrefutable fantasy, the questions concerning Prester John have consequently shifted too.

Instead of asking ‘where were this famous king and country to be found?’, historians now pose different questions. Why did Prester John appear? What impact did his presence have on geopolitical ideas in the medieval and early modern world? Can the legacy of Prester John still be felt today? To answer that, it is necessary to first return to that significant meeting between Bishop Hugh of Jabala and Pope Eugenius III in 1145.

It has long been considered a paradox and point of confusion that, if Bishop Hugh truly wanted to encourage European powers to take up arms and defend Christians in the Holy Land, he should speak of an all-powerful, all-conquering ally, which would render such help redundant. The reason, most likely, is that the legend of Prester John did not begin with Hugh of Jabala’s report but instead existed in oral tradition, spreading through popular folklore long before the mid-12th century.

By suggesting that Prester John’s army was unable to cross the Tigris and subsequently perished in the north, Bishop Hugh demolished faith in this omnipotent and invincible king. Hugh did not want to highlight and boast of the strength of a powerful ally but, instead, show that this ally’s strength had limitations. Europeans could not rely upon the support of Prester John’s army. If they wanted to protect the Holy Land, they would have to do it themselves.

Utopian fallacies

Considered this way, we can see the legend of Prester John for what it really was: medieval propaganda. Deployed for a variety of purposes and assuming different forms and shapes each time, Prester John was a tool which, unquestionably, could have a sharpened edge.

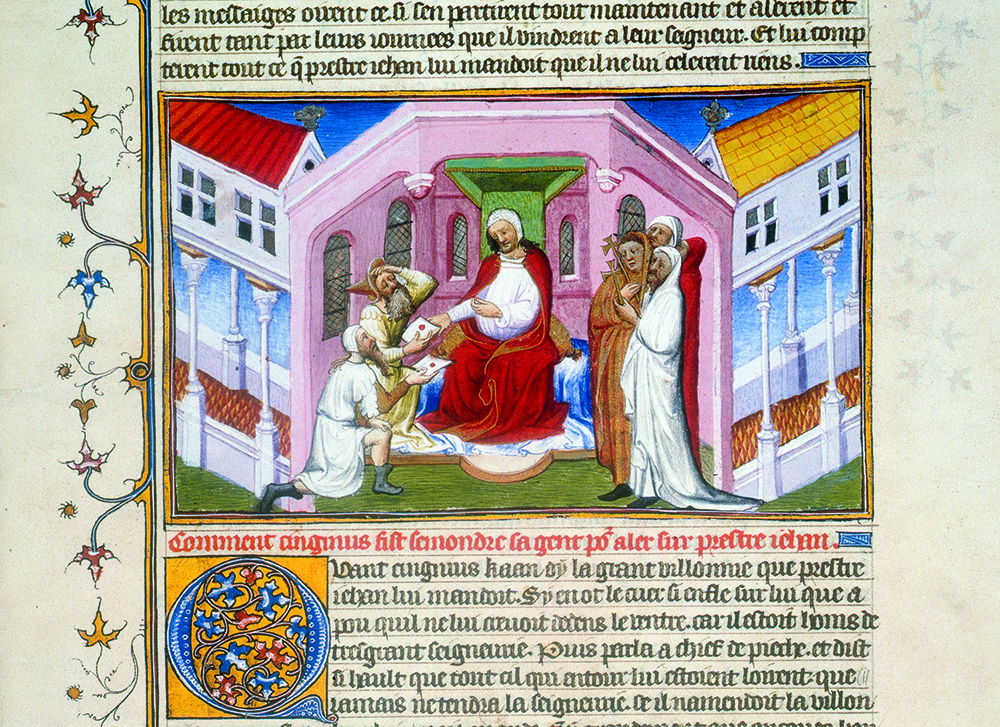

Another example of this can be found in a famous Prester John letter from 1165. The dispatch was first sent to the Byzantine Greek emperor Manuel Komnenos in Constantinople. From there it was sent to the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa. The letter begins:

Prester John by Almighty God and the Authority of our Lord Jesus Christ King of Kings, ruler of rulers, wishes his friend, Manuel, Prince of Constantinople, health and prosperity by God’s mercy ... If indeed you wish to know wherein consists our great power, then believe without doubting that I, Prester John, who reign supreme, exceed in riches, virtue, and power all creatures who dwell under heaven. Seventy-two kings pay tribute to me. I am a devout Christian and everywhere protect the Christians of our empire, nourishing them with alms.

This often-overlooked opening requires particular attention. While Prester John refers to his subordinate vassals as ‘Kings’, he insinuates that the legitimate emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, Manuel Komnenos, is merely the ‘Prince of Constantinople’. This obvious and intentional lack of respect would not have initiated friendship and amity as the letter insists is its purpose, but would have instead resulted in condemnation and a severing of all diplomatic ties.

The author of the letter – the European forger – knew his audience well. For those in the Catholic West, the humiliation, even imaginary, of the Orthodox emperor of Constantinople would have been accepted and applauded by all who read it. The mid-12th century was a period of religious division between the Western and Eastern branches of Christianity. By having Prester John blatantly belittle the Byzantine emperor, the letter suggests that this powerful king endorsed the superiority of Roman Catholic doctrine over that of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Another example of the way the legend was used for propaganda in medieval Europe centres around the sovereign status of John himself. In the letter, John proclaims himself ‘Rex et Sacerdos’ (King and Priest). Amid the near constant conflict between the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, he is posited as a utopian alternative to the division and hostility between religious leader and governmental leader. Prester John is a figure who combines these roles, both the sacramental and the administrative.

Over the following centuries, the undying figure and kingdom of Prester John would be continuously deployed in varying forms and for varying purposes. Marco Polo encounters the kingdom of Prester John in his Il Milione (Travels of Marco Polo) of 1300, perhaps to highlight the breadth and significance of his journey. Likewise, Sir John Mandeville – himself likely a product of imagination – meets with John in the tales of his adventures, in circulation from the mid-14th century. By 1400 Prester John was again called into life to facilitate fresh ideas of Islamic conquest. A letter written by Henry IV of England to Prester John details a thorough plan of how both Henry and John should concurrently invade Jerusalem and capture the Holy Sepulchre from the city’s Muslim inhabitants.

Prester John gained even greater relevance during the expansion of global exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Portuguese, positioned at the forefront of this movement, boasted of sustained diplomatic contact with Prester John’s realm, no doubt seeking to exaggerate their own credentials. This fantasy did not fail to capture the attention of their European neighbours. The Legacye or Embassaye of the great Emperour of Inde Prester John, vnto Emanuell Kynge of Portyngale was printed in England in 1533. Its author claims that ambassadors, sent from Prester John, were very warmly welcomed by the Portuguese king, at whose court they ‘remained three years and had there great reputation … until afterwards they tooke their leave and so merely returned safe home again to their country’. This narrative would undoubtedly have placed a feather in the Portuguese cap and provoked envy among every other European nation.

Any purported contact with Prester John, even minimal, appears to have been worn like a badge of honour, a sign of worldliness granted through association with the richest and most powerful ruler on Earth. It is, therefore, no surprise that the notorious Sherley brothers, Anthony and Robert, self-serving adventurers adept at using Eastern monarchs for their own agenda, also professed indirect contact with Prester John. George Manwaring, one of Anthony Sherley’s attendants, records how, upon one of Anthony’s audiences with the Persian Shah Abbas the Great in 1598/99, he was greeted ‘very royally; and the king gave him a crucifix of gold with diamonds, turquoises, and rubies, [and this] crucifix was sent [to] the king from Prester John, as the king himself did show it to us’.

These fallacies of the early modern period hint at the legend’s sinister undercurrent. From its earliest implementation, the story of Prester John was not only used to explore utopian ideas about medieval government and facilitate simple side-swipe insults at the Byzantine emperor, but was deployed time and time again to support European invasions of the Islamic world.

Found in Ethiopia

By the early modern period, the Prester John myth had undergone a substantial geographical shift. Following the reports from Marco Polo, William of Rubruck and others, European thinkers became increasingly convinced that their predecessors were mistaken and that, rather than being located in the extreme Orient of central Asia, the Kingdom of Prester John was instead – unequivocally – to be found in Ethiopia.

Even in this period of travel and exploration, for Europeans, Ethiopia was still a scarcely visited country, known only for being a schismatic Christian kingdom in a poorly defined region, located somewhere to the west of the Nile. It was, therefore, a part of the world where fertile soil was still available for the sowing of legends. The Queen of Sheba, the Ark of the Covenant and now Prester John all found a long-term home within Ethiopian borders. And yet, while Europeans had a very limited understanding of Ethiopia and its peoples, the same cannot be said of the inverse. Far from being a dormant region passively awaiting the enlightenment of discovery, Ethiopians were exploring the streets of Europe long before Europeans had ventured into Ethiopia or any part of sub-Saharan Africa.

Indeed, there is documentary evidence from 1306 which places 30 Ethiopian envoys in the city of Genoa. Their king, Wedem Ar’ad, had sent them into Europe to negotiate a mutual defensive pact with ‘the king of the Spains’. Wedem Ar’ad hoped that if he offered Ethiopian assistance in the struggle against the Moors who were occupying a substantial part of the Iberian Peninsula, the Spanish would be willing to assist him in their conflict with neighbouring Arabs. This diplomatic objective did not amount to any action. The reason for this is simple: when Ethiopian Christians did visit Europe, what they ultimately found was not a welcoming reception based on religious similarity, but one which oppressed them for their sectarian difference. For generations, Europeans had fantasised about a community of Christians beyond their geographical knowledge. But when they actually encountered one, they greeted it with hostility.

This is clearly demonstrated in the English archbishop George Abbott’s A Briefe Description of the Whole Worlde, written in 1599. In this overview Abbott criticises the doctrinal heresies of Prester John’s religion, stating that:

The people therefore are Christians: as is also their prince: but differing in many thinges from the West Church: they doe to this day retaine Circumcision [for] they did receiue the ceremonies of the Church vnperfectly.

This notion of European superiority concerning Prester John was not an isolated incident, nor was it limited to matters of religious doctrine. In the prejudiced writings of the Venetian traveller Niccolò de’ Conti, we see further proof of how Prester John’s reputation as the most magnificent ruler on Earth was rapidly deteriorating. De’ Conti expressed that, in the land of Prester John:

You will meet with bestial people unable to govern themselves, and although there are monstrous things to be seen they are not enough to give you satisfaction. You will see heaps of gold and pearls and precious stones, but what shall they profit you since the people are beasts who wear them?

This demonisation perhaps reaches its zenith in Ludovico Ariosto’s epic poem, ‘Orlando Furioso’ (1532). At one point in the story, Orlando’s friend Astolfo journeys into Ethiopia where he encounters the emperor of that land. The Prester John figure of this narrative is vilified and dealt severe punishment for his great pride. He is blinded and, together with his people, is subjected to perpetual hunger, as their food and drink are attacked and destroyed by the mythical creatures that once lived alongside them. Such was the European hunger for new lands, for new wealth, for religious domination and for overall power, that they even grew to detest the hero of their own making. Prester John, once glorified as a saviour, had been reduced to an adversary.

The Prester within

In the European mind, Prester John reigned in some distant kingdom beyond geographical knowledge for more than half a millennium. This legend can be considered one of the earliest examples of how Europeans have attempted to imaginatively control the civilisations of Africa and Asia. In the medieval and early modern period, when European Christians failed to conquer the Islamic world by force, they instead tried to achieve its conquest through the creation of legend, conjuring an ally where none was to be found. A trading partner, where none existed.

The quest for the legendary Prester John does not, therefore, take us to the furthest corners of the Earth. Instead, it takes us into the medieval mind. In it, we encounter their hopes and fears. Many of these aspirations – territorial gain, the coveting of the perceived wealth of the East, religious hegemony and racial persecution – outlived the mythical king who embodied them all.

Thomas Collins is a PhD student at the University of Sussex, working on the role of Persia in 17th-century literature and culture.

Source: History Today Feed