Sun Tzu and the Art of Becoming Famous - 6 minutes read

Sunzi’s (Sun Tzu) Art of War is rightly seen in China and the West as one of the greatest works on strategy ever written. ‘Sun Tzu’ is invoked not only in books on war, but on business and dating, and is presented in the West as the key to understanding the current strategy of the Chinese government. For most people Sunzi is the only strategist they know and the Art of War is the only work on strategy they may have read. Yet there was no individual Sunzi (‘Master Sun’) and the interpretation in the West of the work attributed to him is based much more upon a modern Anglo-American reading than anything produced in China over the last two millennia.

A work attributed to Sunzi was widely known by at least the third century bc, when its precepts were harshly criticised by the Confucian philosopher Xunzi. Modern archaeological finds have confirmed that the current version is largely unchanged since then. The first biography of Sunzi was produced around 91 bc by Sima Qian in his Records of the Grand Historian. That biography was a distorted reflection of another, historical, general. But since at least the 11th century some Chinese scholars were also aware that no general matching the description of Sunzi appears in the historical accounts of the time.

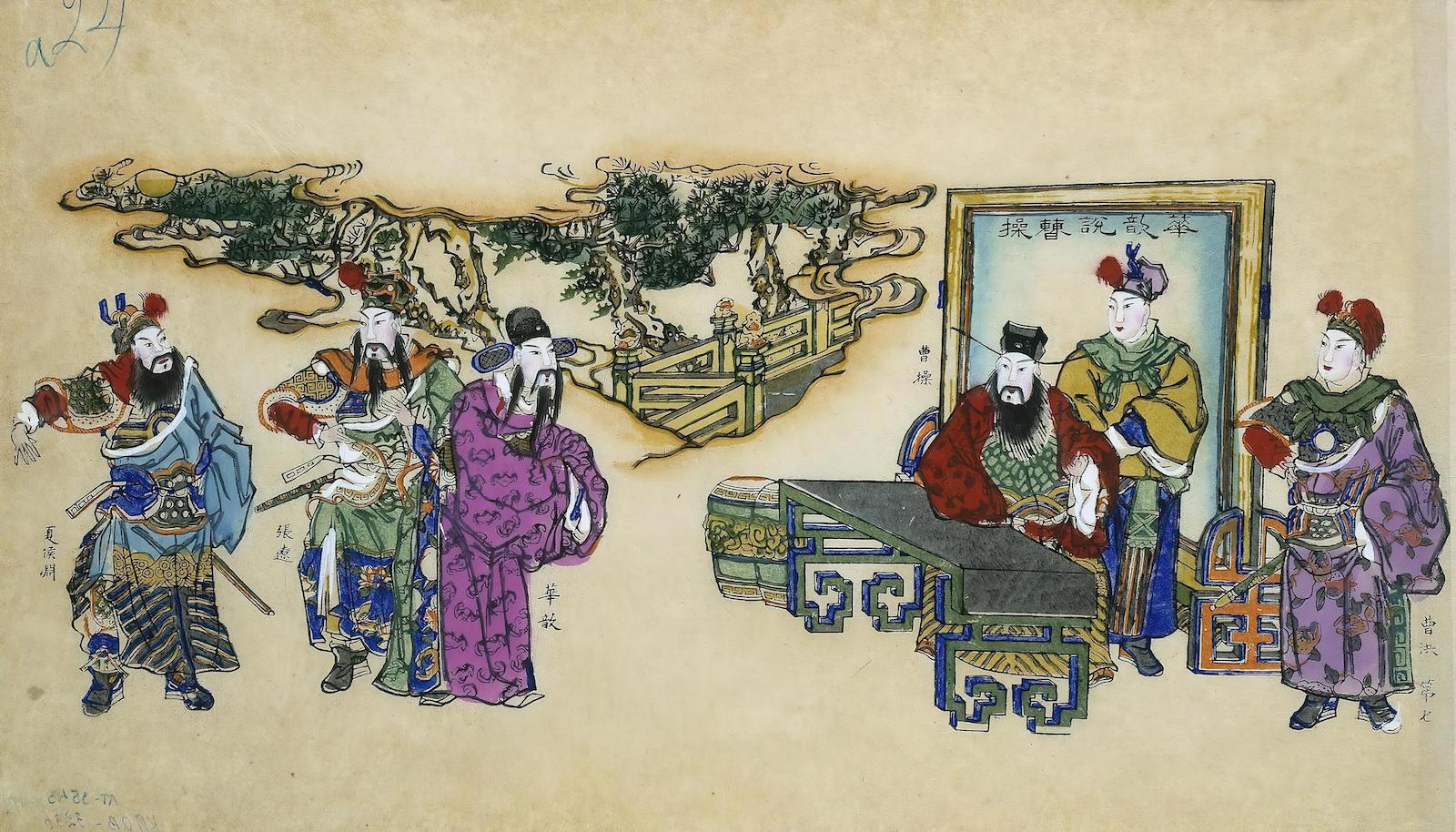

Sima Qian’s biography encouraged the transformation of Sunzi into the author of a classic text on strategy, though. In the third century, Cao Cao, an official who would subsequently become one of the most famous warlords in Chinese history, wrote a commentary on the Art of War. As the first commentary on Sunzi to be transmitted over the centuries, and one written by someone who became famous for his strategy, it retained pride of place in the commentarial tradition.

That commentarial tradition initiated by Cao Cao has continued until today, though whereas premodern commentators generally do not appear to have served as generals before trying to explain the meaning of the Art of War, a number of modern commentaries have been written by retired generals.

As with strategic works in other cultures, it is impossible to connect directly the Art of War with the conduct of

a particular military campaign or battle. Yet from the third to the 13th centuries many commentators explained the aspects of the Art of War that appeared to them to be confusing, presumably to aid in developing military and strategic judgement among literate government officials. These were extremely well-educated men who often disagreed with each other over the interpretation of the Art of War, spending great effort in explaining the antiquarian meaning of terms, and citing many other classic texts of history and philosophy to clarify obscure passages.

The Art of War was one of dozens and dozens of military books written in China, but it received the overwhelming majority of commentary and discussion. So central was it to Chinese military thought that Father Amiot, a Jesuit priest living in China in the 18th century, chose to translate it into French as the paradigmatic Chinese work on the subject. First appearing in Paris in 1772, Father Amiot’s was the first Western translation of the text.

The earliest English translation of the Art of War did not appear until 1905, produced in Japan by British artillery officer Everard Ferguson Calthrop with the help of his Japanese teachers as part of his training. Calthrop reported that the Art of War deeply influenced Japanese strategy (although it is impossible to determine how accurate this is), and that the text was highly regarded by the Japanese military, although the Japanese military was not highly regarded in Europe at the time. This was followed by Lionel Giles’ 1910 translation. Giles was far superior to Calthrop as a reader and translator of Classical Chinese, but neither man’s work was influential at the time. The Art of War remained a somewhat obscure Chinese work on strategy even among military writers, who were themselves a tiny minority within Western military establishments. Sunzi was seen more as an exotic ‘oriental’ artefact than a source for strategic wisdom.

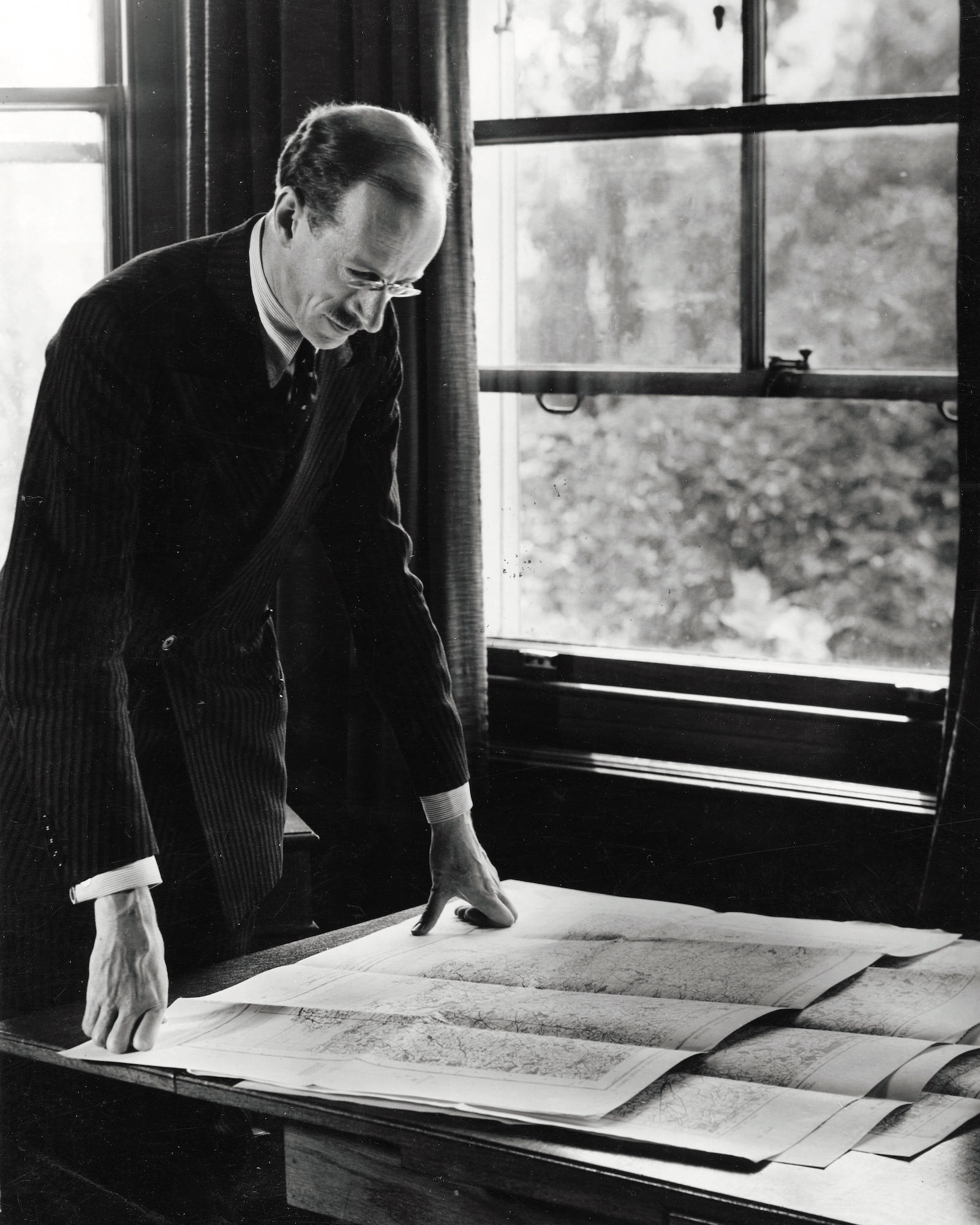

It was only in 1963, with Samuel Griffith’s translation of the Art of War, that Sunzi began to be widely known in the West as a major work of strategy. Griffith was a former United States Marine Corps general who had served in China and in the Pacific during the Second World War. After retiring, he went to Oxford to do his PhD, his dissertation being a study and translation of the Art of War. He was also the first English translator, in 1940, of Mao Zedong’s 1937 work On Guerrilla Warfare. In his dissertation, he explicitly connected the two: ‘Mao Tse-Tung has been strongly influenced by Sun Tzu’s thought.’

Griffith befriended the British strategist Basil Liddell Hart, who reviewed and commented on Griffith’s work. When it was published in 1963, Liddell Hart wrote its preface, claiming, conveniently, that Sunzi argued for ‘indirect strategy’, the same approach to strategy that Liddell Hart himself had proposed – that is, that it is best not simply to throw the full force of an attack on an opponent’s position, a lesson he learned from his experiences on the Western Front. (In historical terms, blitzkrieg rather than trench warfare.)

The combination of Griffith’s position as veteran of the Second World War with service in the Pacific, his translation of Mao Zedong’s work which took on great significance with the many Cold War insurgencies, and Liddell Hart’s preface, provided Sunzi with a new credibility and relevance in the West. Strategy itself as a practice had been elevated by the Second World War and the Cold War, simultaneously moving out of the purely military realm for the first time. Sunzi had the advantage of being much shorter and more comprehensible than Western thinking on strategy. At the same time, American difficulties in defeating insurgencies – in Vietnam, for example – suggested that alternative, non-Western approaches to strategy might be valuable.

Since the publication of Griffith’s translation, Sunzi has therefore come to be interpreted in the West as arguing for indirect strategy. This has little to do with Chinese interpretations and very much to do with Liddell Hart. Liddell Hart’s indirect strategy was more defined by what it was not, a direct force-on-force clash, than what it was. This vagueness allowed it to exemplify the idea that strategy was the means by which a weaker force defeated a stronger force, or at least efficiently defeated an opponent with a precisely aimed attack requiring a minimum of destruction. Liddell Hart has been largely forgotten, but his strategy, now attributed to Sunzi, lives on in the popular imagination.

Peter Lorge is Associate Professor of Pre-modern Chinese and Military History at Vanderbilt University and the author of Sun Tzu in the West: The Anglo-American Art of War (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Source: History Today Feed