Monumental Record | History Today - 6 minutes read

In 2013 archaeologists uncovered what has since been called ‘the greatest discovery in Egypt in the 21st century’: hundreds of papyrus fragments dating to the last years of King Khufu’s reign (c.2500 BC) at the oldest harbour in Egypt, a site on the Red Sea coast called Wadi al-Jarf.

Excavations, led by Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard, began in 2011. Work had been ongoing along the coast for some years with the goal of learning more about ancient Egyptian trade with the mysterious land of Punt and of expeditions to Sinai for copper and turquoise extraction. The team excavated drystone buildings, a worker’s camp, kilns and 30 storage galleries cut up to 30m into the hillside. These galleries held lengths of rope, wooden boat parts and ceramic storage jars. Each was used by a single boat, allowing it to be dismantled and stored safely, sealed at the entrance by a large stone block. A long, L-shaped stone jetty, still visible at low tide, stretches out into the sea, creating a sheltered dock where more than 21 stone anchors were found in situ. Some of these are inscribed with short hieroglyphic texts that may be the names of boats.

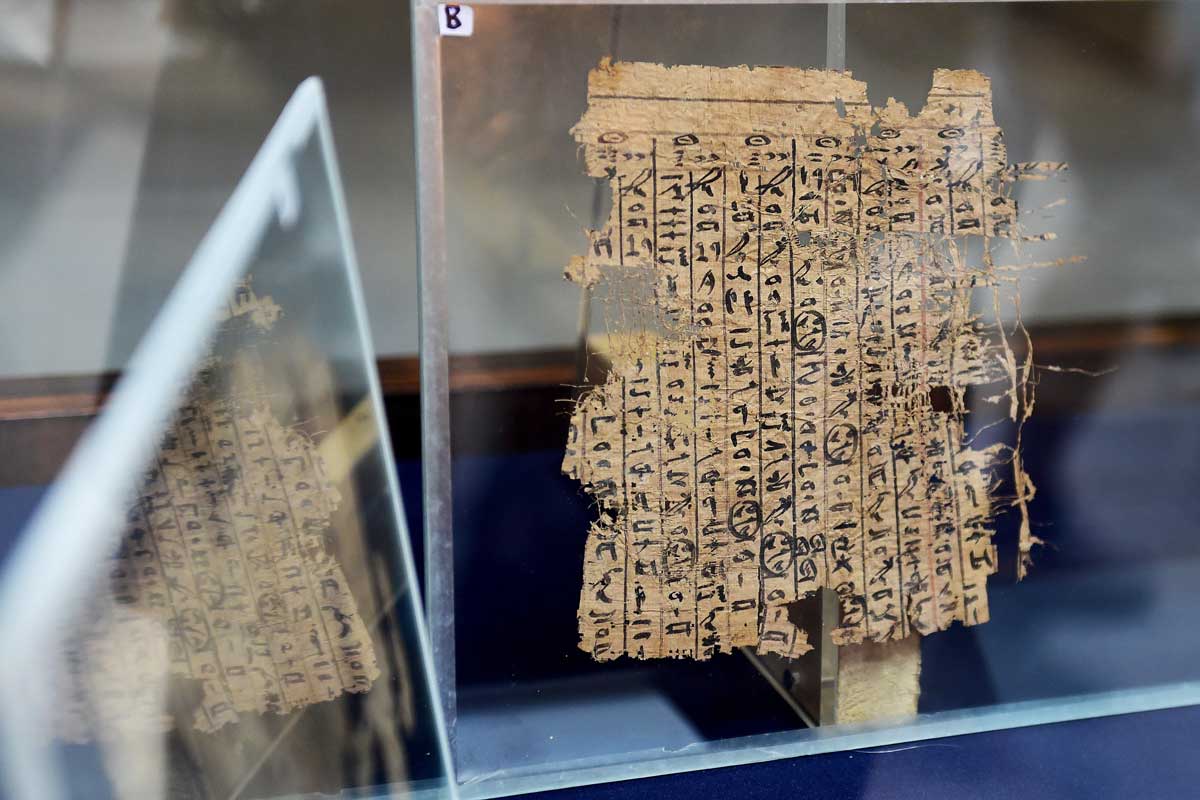

While clearing spaces in front of the galleries the team found over 400 papyrus fragments, from which seven documents have so far been reconstructed. Some are dated at the top of the page to ‘The year after the 13th cattle count’ of King Khufu, meaning around year 26 or 27 of his reign. This makes them the oldest papyrus documents yet found.

Two types of document can be identified at Wadi al-Jarf: accounts and logbooks. The accounts detail the movement of the bread, beer, cereals and meat to feed the workers. This was their payment, as coinage was not used in Egypt until c.360 BC. The documents are laid out like a modern spreadsheet, showing what was needed, what had been delivered and what was still owed. Feeding the estimated 20,000-strong workforce spread across the pyramid site, quarries and transport teams would have been an immense commitment; the papyri reflect this, as different areas of Egypt take turns to deliver foodstuffs.

To date, two of the logbooks have been published: one written by an inspector called Merer and one by a scribe named Dedi. Both men worked as part of a team, or aper, of around 1,000 workers called ‘The Followers of “The Uraeus of Khufu is its Prow”’, whose name is well-attested on storage jars at Wadi al-Jarf. This team was divided into smaller crews of around 40 workers known as a saa or phyle, which were named ‘The Big’, ‘The Small’, ‘The Asian’ and ‘The Prosperous’. Merer led ‘The Big’ crew, while Dedi oversaw the work of all four crews centrally. Other inspectors are also named in the documents, although their names are sometimes incomplete: Mesou, Sekher[…] and possibly [Ny]kaounesut lead the other crews. Together with the account books we can trace almost a year’s activity, from June to May. From his writing, which is heavy with ink at the start of each column, we can tell that Merer wrote his journal daily, detailing the work of his team in bureaucratic detail. Their main work was transporting limestone blocks from the quarries of ‘Ro-Au’ (Tura) to the site at Giza about 15-20km away. These bright white blocks were the casing of ‘Akhet Khufu’ (‘Horizon of Khufu’), as the pyramid was named, which provided an awe-inspiring finish to the structure that has since been removed, reused or lost (the internal blocks that are visible today were quarried close to Giza). Merer records what his team did each day and night, with occasional notes for the morning and noon activity.

‘The Big’ crew are described hauling stones at Tura, before loading cargo boats (usually a single boat, but sometimes up to five vessels at one time) and travelling two days down the Nile to Giza ‘loaded with stones’. The unladen return took only one day. The crew completed a round-trip between Giza and the quarries at Tura two or three times in each ten-day Egyptian week. This could only have taken place around the time of the yearly flood, when the high waters of the Nile made it more navigable for heavily laden vessels. It has been calculated that the boats could have carried a load of 70-80 tons, about 30 of the 2.5 ton blocks used to clad the pyramid of Khufu. This would mean that ‘The Big’ crew could have moved around 200 blocks a month; 1,000 in the period when the river and canals were navigable. Merer notes the presence of ‘the nobleman Ankhhaf’ serving as the Director of ‘the entrance to the Pool of Khufu’, probably an artificial lake, used as a staging post on the northbound journey from Tura to the Giza Plateau. Ankhhaf was Khufu’s half-brother, Vizier (prime minister), Director of Royal Works and ostensibly the pyramid’s project manager during its completion. He was buried only a stone’s throw from the pyramid in a tomb in Giza’s eastern cemetery.

Merer and Dedi’s records help us to flesh out the geography of lower Egypt and the network of canals and harbours that enabled the movement of stones, workers and supplies to the pyramid site. The teams were highly skilled and versatile, not only moving material for the pyramid and temples, but also engaging in storehouse management, potentially constructing a dock in the Delta and taking part in mining missions to Sinai. Merer and Dedi’s logbooks and the accounts books were left behind at Wadi al-Jarf, possibly after the crew’s final assignment there at a time when the Red Sea could be navigated. The site was closed, and operations under Khufu’s successor, Khafre, took place at Ain Sukhna to the north.

The survival of these documents is extraordinary, as is the unique sapshot they provide of the lives of dozens of workmen who were witnesses to the construction of a wonder of the ancient world. The personnel lists, delivery slips and other accounting documents are still to be published and they will surely add even more to our understanding, all of which we will be reading through the pens of Merer, Dedi and their colleagues.

Dan Potter is an Egyptologist and Assistant Curator at National Museums Scotland.

Source: History Today Feed