The Case for High Wages - 6 minutes read

The recent Conservative leadership campaign saw candidates offer both tax cuts and increased government spending, which led to much critical commentary, especially over whether the Conservative Party had abandoned its historic reputation for financial rectitude. Following nearly a decade of austerity, however, such pledges seem likely to be aimed at gaining the favour of voters, rather than signalling an ideological shift.

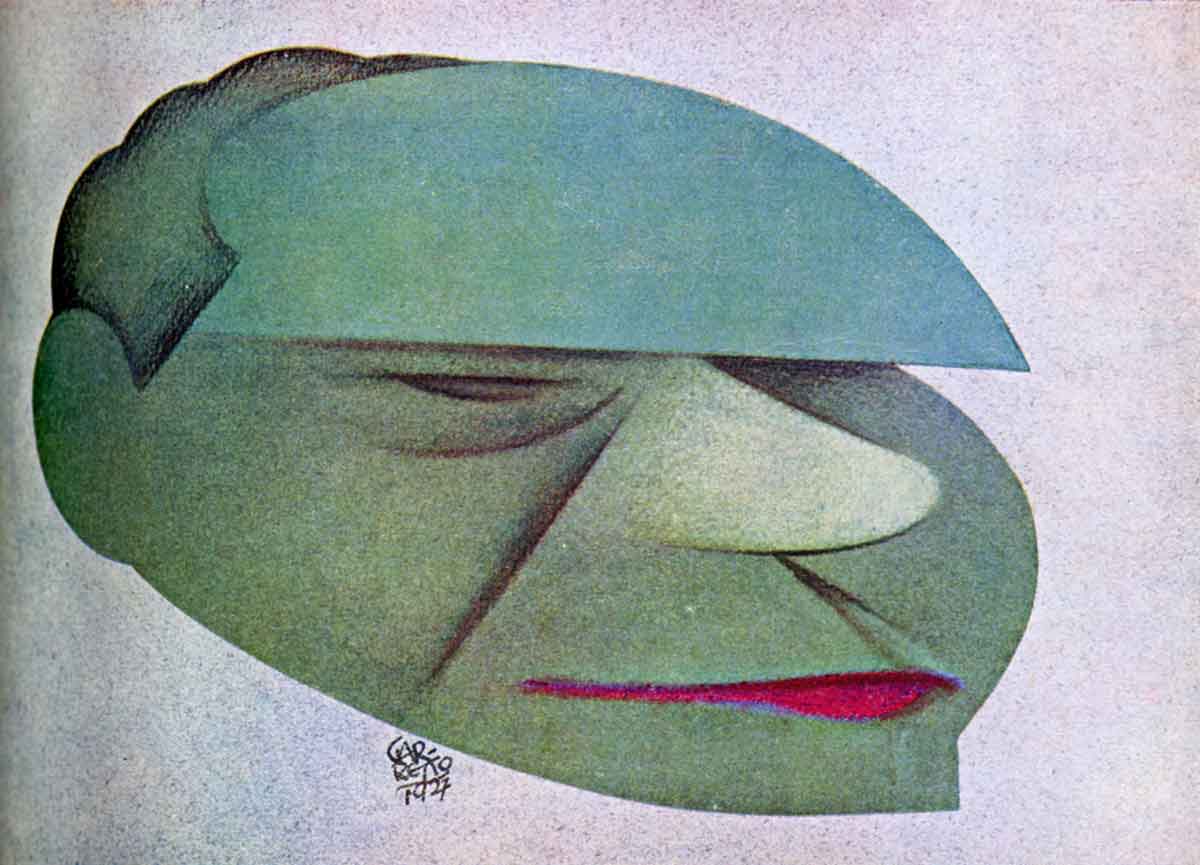

Regardless, such promises bring to a mind a conservative figure – though one who often had a fractious relationship with the Conservative Party – who truly believed in such an approach. Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, used his three newspapers – the Daily Express, Sunday Express and Evening Standard – to promote his belief that cutting taxes while raising wages (in both the private and public sectors) and funding government works programmes would lead to a virtuous cycle of economic growth. A.J.P. Taylor’s 1972 biography placed Beaverbrook within an ‘expansionist school’ alongside such characters as the economist John Maynard Keynes and politicians as different as Harold Macmillan and Oswald Mosley.

An important part of Beaverbrook’s vision for promoting economic growth was a manageable level of inflation, which he believed would encourage businesses to invest and consumers to buy. In the 1920s, therefore, he backed leaving the Gold Standard to allow the government to promote reflation by printing more money. Similarly, conventional wisdom suggested regular wage increases would lead to runaway inflation, but high wages were central to Beaverbrook’s plan. Even many in the Labour Party failed to match Beaverbrook’s willingness to push for high pay due to fears of inflation. As Taylor stated: ‘Beaverbrook was peculiarly challenging even among the heretics.’

High taxes would hamper businesses and undermine the profit motive, Beaverbrook argued. He was a champion of imperial preference, which, aside from his belief that it would ensure the Empire’s continuation, would, he argued, raise government funds through tariffs on foreigners, rather than British and imperial citizens. Imperial preference and low taxes were popular ideas among Conservatives; his calls for high wages and government spending were not.

Gregory Marchildon argued that Beaverbrook’s expansionist outlook was formed while venturing into business and politics in Canada. During an inflationary cycle between 1896 and 1913, Beaverbrook, and many fellow Canadians, made their fortunes. He was also inspired by Henry Ford, who believed that, if the working classes could partake in the expanding consumer culture thanks to higher wages, they would be less likely to turn to socialism or trade unions. Ford argued that high wages would benefit both the businesses that offered them – attracting skilled workers and keeping them motivated – and the economy as a whole, as more workers with more expendable income would lead to increased consumption and profits.

Beaverbrook’s micromanagement of his newspapers ensured his expansionist views were strenuously promoted. He lent support to Lord Rothermere’s 1919-22 Anti-Waste campaign, as the vast national debt accrued during the First World War was deemed a unique challenge. The campaign achieved its aim, helping usher in the Geddes Axe in 1922, a programme of drastic cuts in public expenditure.

After 1922, however, Beaverbrook’s papers argued consistently against retrenchment, while still calling for lower taxation. At this time, most Conservatives preached further retrenchment, orthodox economic thought argued it was necessary and even senior Labour politicians believed it was unavoidable. Beaverbrook, however, did not want a proliferation of bureaucrats, preferring private enterprise where possible.

Yet he wanted high wages for civil servants, as well as private sector employees. He dictated the editorial line of his newspapers; correspondence with Beverley Baxter, editor of the Daily Express, was duly followed by an editorial on 27 July 1929 that restated Beaverbrook’s attack on the common refrain: ‘The Parrot Cry – “Cut Wages!”’ Beaverbrook published in 1930 a pamphlet called High Wages: A Manifesto to Trade Unionists, and agitated for high wages in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 1931.

An intense six-month campaign for high wages began in January 1933. Further articles declared: ‘High Wages Make More Trade’ and ‘Employers Urged To Keep Up Wages During 1933 – “The First Essential To Trade Recovery”’. With the war over and a Labour government in power, a front-page article in February 1946 sternly admonished the government that ‘You promised the workers who voted Labour that you would give immediate increases in wages’ and beseeched it to ‘Fulfil that election pledge’.

This was not mere rhetoric. Just as Ford had introduced a $5-a-day wage in 1914 and increased wages following the Wall Street Crash, Beaverbrook paid his employees generously. In High Wages, a section titled ‘Lessons of Britain’ told the reader that high wages resulted in prosperity. As illustration, it surveyed an industry ‘prosperous beyond dispute’ – newspapers and, in particular, the Daily Express.

Beaverbrook and his newspapers also consistently advocated public works to alleviate unemployment. As structural unemployment grew in the 1920s, an editorial titled ‘Work not Doles’ argued that ‘when a man is unemployed owing to no fault of his own it is the duty of the State to make decent provision for him’, with public works always preferable to the ‘ruinous and vicious system of the doles’. In October 1933, a Daily Express front page championed the ‘Vast Schemes To Keep the Big, Bad Wolf [of unemployment] at Bay’ around the world.

Beaverbrook did not fit the typical Conservative mould. But he was not a voice on the margins. His radical ideas were presented to millions of readers. The circulation of the Express titles has greatly diminished over recent decades and they now have a reputation for being staid and traditionalist, consumed by an ageing middle-class readership, but in 1940 the Daily Express was the most widely read daily newspaper in the world with a circulation of 2,546,000 and a young, diverse readership. It seems likely that Beaverbrook’s expansionist ideas helped contribute to the left and sections of the right backing a more expansionist state from the 1940s and the ensuing onset of the ‘Affluent Society’ in the 1950s.

Aaron Ackerley is Associate Tutor in Modern British History at the University of Sheffield.