Did Britain Ever Have a Revolutionary Moment? - 8 minutes read

‘European observers viewed Charles I’s execution as an unprecedented, revolutionary move’

Edward Vallance, Professor of History at the University of Roehampton

Contemporaries were in no doubt that the trial and execution of Charles I in 1649 were revolutionary. It was widely expected that the proceedings would culminate in the establishment of a new republican government. James Butler, Marquess of Ormond and leader of the Royalist forces in Ireland, saw the New Model Army’s Remonstrance of November 1648, which called for the king’s trial, as seeking the ‘totall change of our gouernement & to lay the foundation of their new one in the blood of our master & the ruine of his posterity’.

European observers viewed Charles I’s condemnation and execution as an unprecedented revolutionary move, which represented an existential threat to the continent’s monarchies: ‘History affords no example of the like’, wrote the Venetian ambassador Alvise Contarini. Contemporary newsletters noted how, even before the king’s death, the army and the Rump Parliament stripped away regal dignity by referring to the reigning monarch as mere ‘Charles Stuart’. They observed how the court dispensed with the royal coat of arms and instead created new insignia, pointing again at England’s imminent republican future.

The trial, therefore, was designed not merely to deal with a troublesome monarch, but to affirm the supremacy of the House of Commons as the representative of England’s sovereign people. The court did away with all distinctions of rank for, as the president of the court, John Bradshaw, told Charles: ‘Justice knows noe respect of persons.’ The king would be condemned on the basis of the evidence of lowly witnesses: cobblers, butchers and vintners. As the Earl of Clarendon put it, this was a court which ‘made the greatest lord and the meanest peasant undergo the same judicatory and form of trial’.

Those who orchestrated the trial were determined, too, that it was conducted in the most public fashion possible: the proceedings were held in the vast space of Westminster Hall, before thousands of spectators. Thousands more followed the trial in printed newsbooks. The clear intent was to stage a revolution to which, as the regicide and Fifth Monarchist Thomas Harrison would put it, ‘the world should be witness’.

‘The year most likely to result in a revolutionary moment was 1839’

Katrina Navickas, Reader in History at the University of Hertfordshire

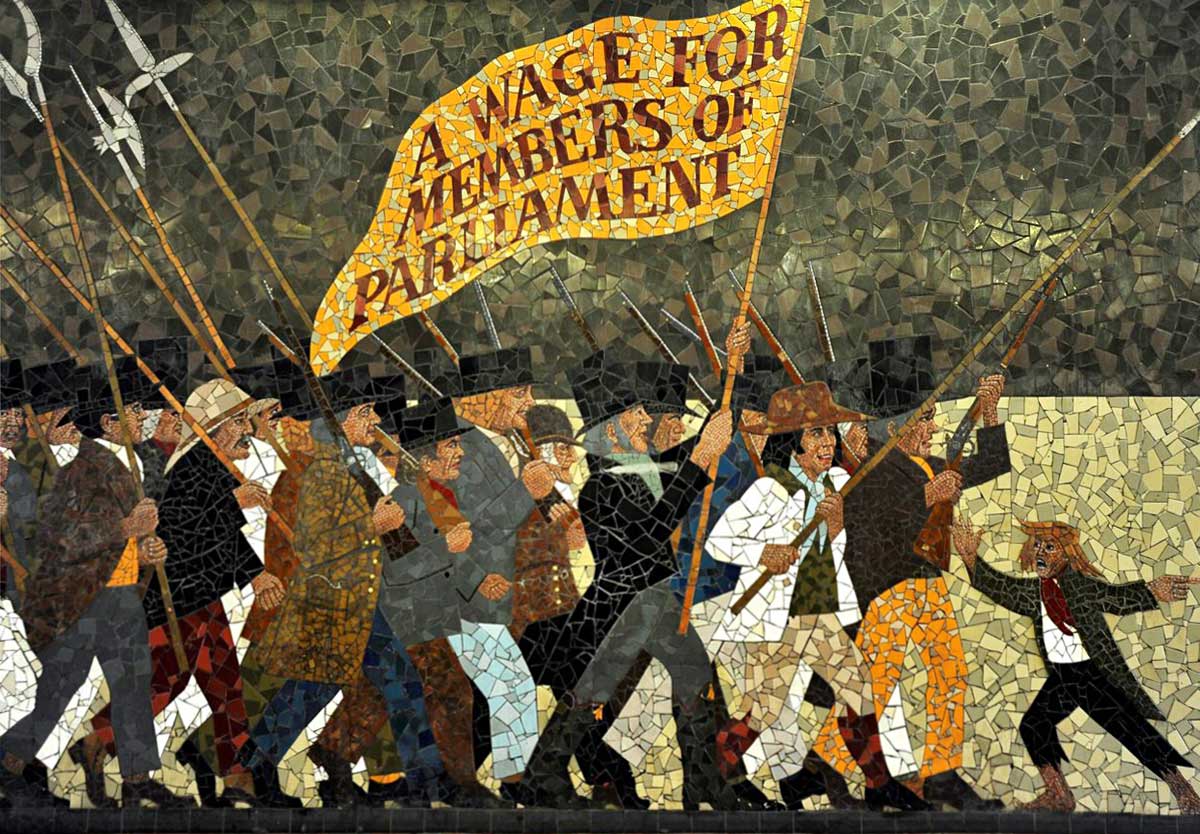

From 1776 to 1848 British radicals had many examples of revolution to emulate. Yet, in comparison with republican and independence movements in Europe, the Americas and the colonies, Britain never got close to revolution. Most activists sought representation rather than a republic. When popular movements did attempt ‘risings’, however, it required the full force of the military to suppress them.

The year most likely to result in a revolutionary moment was 1839. Bread prices were at their highest levels since 1819. Peaceful demonstrations built up to the presentation to Parliament of the first Chartist National Petition in May, signed by over 1.2 million people. Even in more moderate centres, such as Birmingham, there was growing support for a National Convention to take ‘ulterior measures’ if the petition was rejected.

The South Wales valleys fostered the greatest potential for revolution. On 19 April, the London Chartist Henry Vincent gave a speech in Newport which he concluded with: ‘Death to the aristocracy! Up with the people, and the government they have established!’ The magistrates banned all meetings, leading to riots. Monmouthshire draper and Chartist John Frost issued an open letter describing the magistrates’ edict as ‘a declaration of war against your rights as Citizens’. The National Petition was rejected in July. On 3 November 7,000 armed men gathered in three contingents at Pontypool, Blackwood and Ebbw Vale to march on Newport. On the arrival of one section at the mayor’s headquarters at the Westgate Hotel, fighting led to at least 24 dead and over 50 injured; 21 Chartists, including Frost, were charged with treason and transported to Australia.

The 1839 rising failed, but it was a close call. The Rural (county) Constabulary legislation had only just been enacted, so police forces were thin on the ground. Just 60 soldiers were stationed at Newport. Neither the police nor the military were as practised in crowd dispersal as they would become by 1848. If the leaders had succeeded at Newport, perhaps Vincent’s rhetorical claim that Wales could become a republic would have been closer to realisation.

‘Henry VIII’s Break with Rome represented a truly revolutionary moment’

Manolo Guerci, Senior Lecturer, Kent School of Architecture and Planning, University of Kent and author of London’s ‘Golden Mile’: The Great Houses of the Strand, 1550-1650 (Yale University Press, 2021)

If ever there was a revolutionary moment in British history, it was given life through architecture. It is not the coming of Inigo Jones, the much celebrated surveyor of the King’s Works, important though he was in developing classicism across the Channel; nor was it the spread of Palladianism, which shaped much of the 18th century and a certain aspect of Englishness. It is, by contrast, the eclectic and whimsical mixture of Italianate and the traditional medieval, chivalric language put forward by Henry VIII and developed throughout the Elizabethan period by the new political elite, which emerged from, and triumphed out of, the Dissolution of the Monasteries – England’s truly revolutionary moment.

After the Break with Rome in the 1530s, all was at stake: the need for national stability and new international relations with Europe and beyond, at the dawn of what would eventually become the British Empire. The stage set for this new projection of power was the Strand in London, where all Whitehall’s satellites developed. As the ‘great channel’ between the economic and judicial centre of the City and the religious and political governance of Westminster, this was London’s ‘Golden Mile’. Here, mostly majestically facing the river Thames, 11 great houses, the so-called Strand Palaces, arose from the ashes of the Reformation like new secular cathedrals, bringing conspicuous consumption to an unprecedented level of sophistication. Without them, one cannot understand the development of a truly English style, nor indeed of the country house.

Henry VIII’s Break with Rome represented a genuinely revolutionary moment in England’s governance – something from which the country has, arguably, yet to recover. England adopted the polyglot nature and largesse of the great European courts, while maintaining a unique character, encapsulated in the Strand Palaces, and English architecture more generally, projecting the power of Englishness to the world.

‘Was the early 19th century Britain’s revolutionary moment?’

Emily Jones, Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Manchester

My A-level teacher once asked our class to write an essay on: ‘To what extent’ – Peel later declared – ‘had Britain trembled on the brink of revolution, 1815-1820?’

To the broader question and time frame: if we understand revolution to mean rapid, radical and fundamental change, then the fact that the mid-17th century – civil wars, Irish plantations, republic, regicide – caused so much trouble for the ‘Whig’ historians of the 19th century tells us something important about that period, but also how ‘revolution’ was seen to be something uncomfortable, alien (‘French’). It differed from the supposedly slow, evolutionary path that British political progress had (it was claimed) been set upon for centuries past. Reformation was not revolution, so it was easier to skip this period or avoid it altogether. Even at the turn of the 20th century, debates over the erection of Cromwell statues demonstrated that this legacy was far from settled.

But it was the prospective revolt of the lower classes following Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 that set the scene for that A-level essay. Returning troops faced unemployment as the king charged his queen with adultery. Calls for political change resulted in the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 and the Cato Street Conspiracy. Revolution became associated with Jacobinism. ‘The scum will gather’, Robert Peel declared, ‘when the nation boils.’

Was the early 19th century, then, Britain’s revolutionary moment? We were supposed to answer ‘no’ – or ‘maybe’ at a push. Pragmatic actions were taken, full-blown revolution was avoided. The Whig historians could remain still in their graves. Likewise, we learned that early histories of what Toynbee labelled ‘the Industrial Revolution’ of the 18th and 19th centuries were challenged by later scholars, who rejected the label of ‘revolution’ in favour of an account that stressed deep roots and gradual accumulation, tracing ‘proto’-industrialisation to the 1580s.

Britain has experienced revolutions in thought, politics, society and economics. Rebellion, too, is central to its imperial history: the Indian Rebellion, Morant Bay, Irish Fenianism, suffrage, the Ulster Covenant campaign, to name but a few. Yet a desire to paint Britain as ‘safe’ from revolution has been an enduring habit. Is it still alive today?

Source: History Today Feed