The Land of Frustrated Revolutions - 6 minutes read

‘A frustrated revolution’ is how Eric Hobsbawm described the anarchic conflict in the Colombian countryside in the 1940s and 1950s, known simply as la Violencia. But this appraisal also describes the history of left-wing insurrections across all of Latin America.

Latin America produced Pancho Villa, inspired Che Guevara and gave asylum to Leon Trotsky. At first glance, revolutions seem to spring from its soil. Yet Latin America has produced remarkably few of them. The cases of Mexico in 1910, Cuba in 1959 and Nicaragua in 1979 are not the rule but the exceptions.

On the 40th anniversary of the Nicaraguan revolution and in the year the Cuban revolution turns 60, it is time we realised that, despite its radical icons and rebellious mystique, Latin America is not a region of revolution.

Throughout the 20th century, widespread repression, corruption and inequality led to anti-establishment sentiment in Latin America, but this rarely translated into an overturning of existing social structures. The rebellious cause reached its height in the decade after the Cuban insurrection, when almost every Latin American country had insurgent forces of some kind. But, except for the Sandinista victory against the Somoza dynasty’s dictatorship in Nicaragua, none of these movements became a revolution. Unable to sustain public opinion, they were either put down by the state, transformed into criminal organisations, or simply petered out.

If the Mexican revolution against the 30-year dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz – fought by everyone from large landowners to mobilised peasants – demonstrated the possibility of defeating the army, then the Cuban revolution against Fulgencio Batista was a sea change, invigorating would-be rebels regionwide. However, these new insurgents did not appreciate that Batista’s fall was predicated on circumstances that could not be replicated. And although Che Guevara believed the conditions required for a revolution existed, the Cuban model could not be exported. In Bolivia, which had itself toyed with revolution in the 1950s, Guevara died trying.

Latin America’s longest-running insurgencies are in Colombia. Stemming from la Violencia and galvanised by Cuba, from the mid-1960s two rural groups, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Army of National Liberation (ELN), tried to end the oligarchy’s control of politics. However, by the 1980s both were implicated in drug trafficking, extortion and terrorism, and any hope of securing meaningful public support was gone. Over half

a century on, very few see them as revolutionaries.

In 1970s’ Argentina, the attempt at revolution came not from the hinterland but the city. Trying to overthrow Jorge Rafael Videla’s dictatorship, a military group founded by Juan Perón in the 1950s – the Montoneros – morphed into an urban guerrilla force. They were suppressed during the ‘Dirty War’, when the Argentinian military, backed by the US, engaged in state-sponsored killings of leftists.

Across the border in Uruguay, the Tupamaros fared little better. A guerrilla group, strongest in the early 1970s, they raided banks and distributed food and money among the poor. But after the government began arresting and torturing dissidents, the Tupamaros themselves turned to violence, costing them their popular support.

Even more discredited was the Shining Path, the Maoist insurgency in Peru. From the 1980s to the early 1990s it was responsible for untold deaths of government officials, town dwellers and peasants. It collapsed after a string of defeats and the capture of its leaders Abimael Guzmán and Elena Iparraguirre. It was another case of a revolution frustrated, defeated or disgraced.

Despite the failure of these and other insurrections, there were significant sociopolitical changes in 20th-century Latin America. And although ultimately reversed by rightist coups, some of the most dramatic changes came not through revolution but through democracy.

In the 1950s, Jacobo Arbenz reformed Guatemalan labour and agrarian laws, including nationalising unused land owned by the US conglomerate the United Fruit Company. In retaliation, and to prevent the prospect of socialism in its ‘backyard’, the US supported a coup against Arbenz.

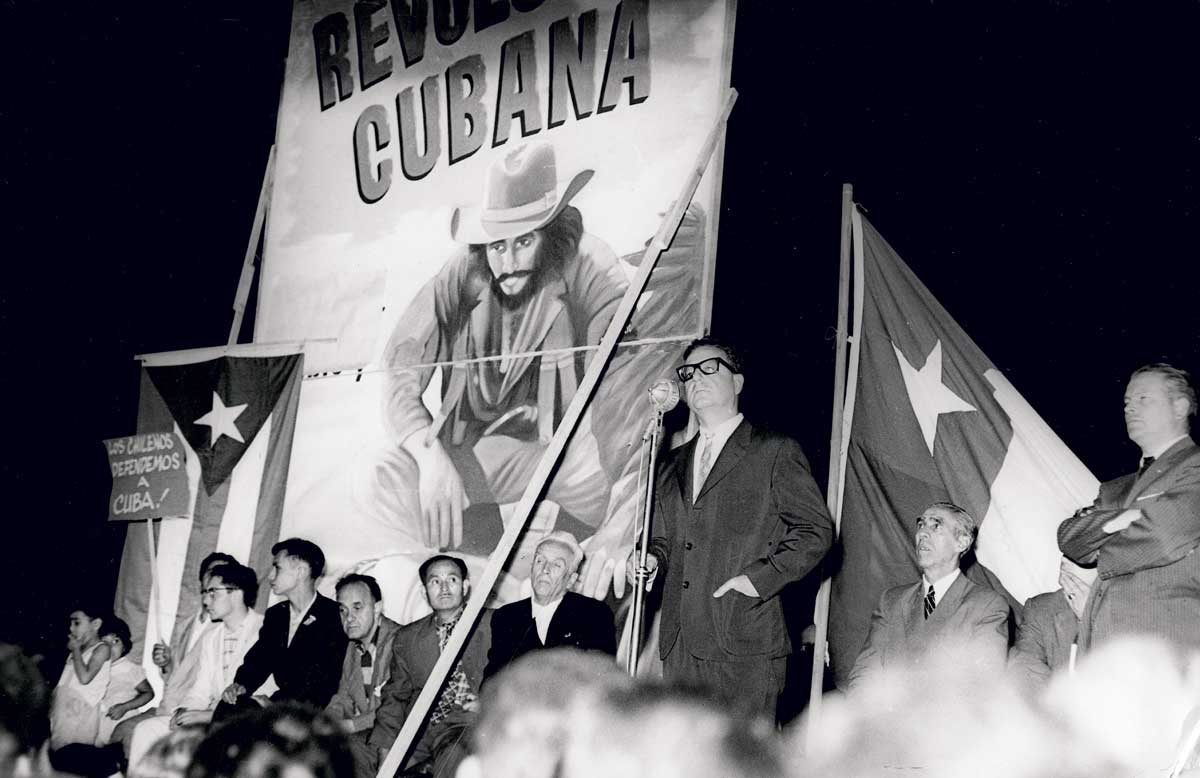

It was a similar case in 1970s’ Chile. Salvador Allende sought to prove that socialism could be ushered in through strong, democratic institutions. Yet, despite being progressive, President Allende’s policies, such as nationalisations of industry, were not revolutionary. The process began under his predecessor and many of the reforms were also supported by Allende’s Christian Democrat opponent. After leading the 1973 coup, however, Augusto Pinochet undid some of Allende’s reforms. Ousted by anti-democratic forces, neither Arbenz nor Allende held power long enough to inaugurate a full, constitutional revolution.

By the turn of the millennium, insurgents’ failures and the example, however brief, of democratically elected socialism in Chile, led to a shift in revolutionary theory, away from armed insurrection. After attempting a coup in 1992, Hugo Chávez came to power democratically in 1998 in resource-rich, socially divided Venezuela, promising widespread reform. In what was dubbed the ‘Pink Tide’ (because its leftism did not extend to ‘red’ communism), Chávez was joined by former guerrilla fighters, such as José Mujica (a Tupamaro) in Uruguay and Dilma Rousseff (once of the Comando de Libertação Nacional) in Brazil. But, despite their rhetoric, these leaders were more reformers than revolutionaries. Even the most vocally radical, Hugo Chávez, did not go so far as to socialise his country’s economy.

Even if we contend that 20th-century Latin America was characterised by revolution, on a global level it does not stand out as a cradle of revolt. Take the Middle East. In the decade after the Mexican revolution, Atatürk made Turkey a republic; in the same decade as the Cuban insurrection, Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew King Farouk; and just a few months before the Sandinistas triumphed, Iranian revolutionaries toppled the Shah. And in the late 1940s, Sukarno, Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh all led revolutions in East Asia.

It is easy to succumb to the romance of Latin American revolutions, with their countercultural icons, derring-do and Robin Hood ideals. But that is to miss the fact that this remains a socially traditional, and often reactionary, region. If Latin America really is the land of revolution, it is one of frustrated revolutions.

Daniel Rey is the author of ‘Checkmate or Top Trumps: Cuba’s Geopolitical Game of the Century’, runner-up of the 2017 Bodley Head & Financial Times essay prize.