The Case of the Cursed Charter - 6 minutes read

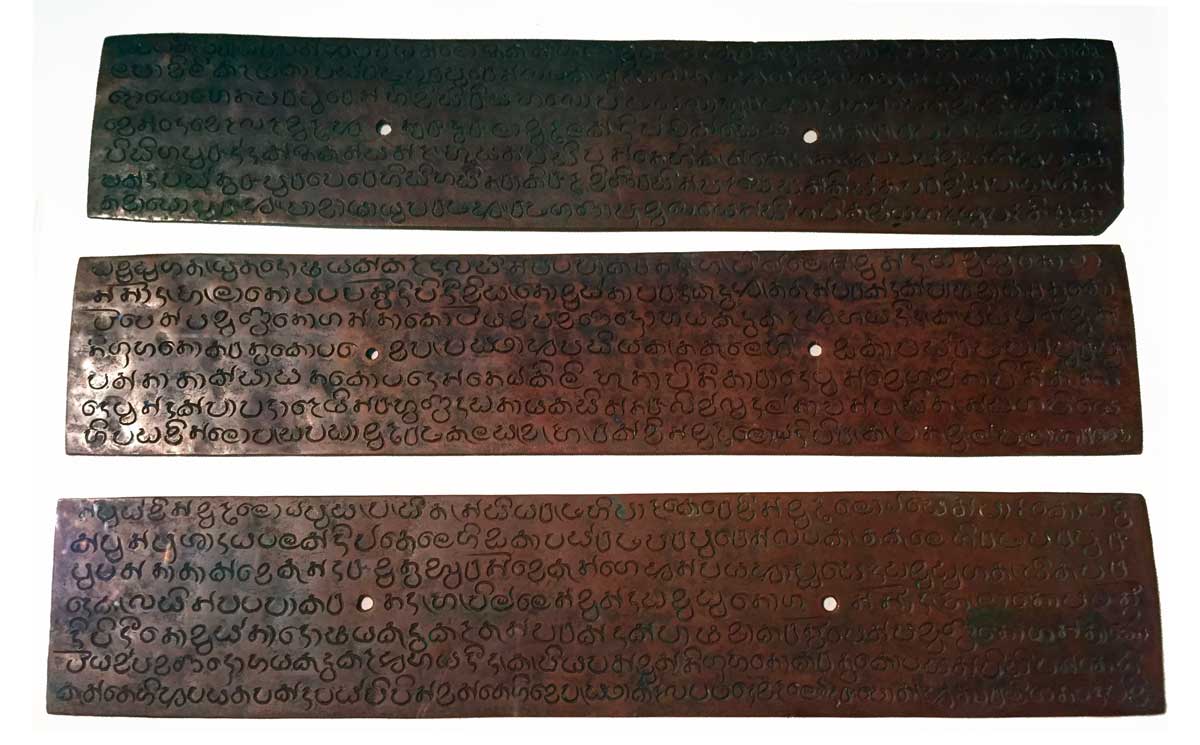

In a report for the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon from 1949, the epigraphist Senarath Paranavitana announced the discovery of the ‘most valuable historical document that Ceylon possesses – the oldest known Sinhalese copper-plate charter’. With this announcement, Paranavitana pushed the date of the earliest copperplate charters back to the king Vijayabāhu I, the subject of the inscription: ad 1055-1100.

The oldest copperplate inscriptions come from fourth-century southern India and are sheaves of copper bound together with a sealed ring. Over the next 600 years copperplates became the predominant political tool for projecting imperial voices and representing royal authority across south India and Sri Lanka.

The charter is spoken in the voice of King Vijayabāhu I himself. He recounts a deeply personal story of his childhood in exile in Sri Lanka’s mountainous hinterland during military incursions into the north of the island by south Indian military regiments and of gradual socialisation into the world of the royal court by his trusted caretaker Budal, himself a high-ranking military retainer in the family’s household. For the service of ‘nurturing [Vijayabāhu] with the sustenance of edible roots and green herbs from the jungle’, Budal and his ‘sons and grandsons’ are granted a wide array of legal protections.

While scholars often approach inscriptions as faithful records of the dates of various types of royal donations for the establishment and maintenance of service to Buddhist monks and Hindu gods, Vijayabāhu’s charter instead offered a glimpse into otherwise hidden social lives and historical experiences.

In response to the discovery, there was a flurry of scholarship from historians and epigraphists that produced competing readings. Despite accusations of forgery, however, the general consensus was that this inscription was unique in its content, recording more than just the res gestae of the king.

Yet, for an inscription that was to go on to upset both the political chronology of medieval Lanka and scholarly definitions of copperplate charters, Paranavitana’s announcement of its discovery in 1949 is remarkably unconcerned with its content. Rather, Paranavitana is almost entirely preoccupied with the uncanny circumstances surrounding the inscription’s discovery by a low-level village official named Suravirage Carolis Appuhamy on his way ‘to work in his field, Bōgahadeniya, to prepare it for the seasonal cultivation’.

Not long after Paranavitana received word that Appuhamy’s ‘hoe had struck something hard … a lump of corroded metal covered with strange writing and earth’ did stories begin to trickle back to Colombo about how the inscription’s discovery ‘disturbed the even tenor of Carolis Appuhamy’s life’. First, there was illness. Paranavitana reports how a family-wide sickness convinced Appuhamy and his friends ‘that the copper-plates, reposing somewhere in his house, were the cause of the maladies from which his loved ones were suffering’. An unsuccessful harvest followed. In response, Appuhamy ‘resolved to rid himself of the gift which had brought him nothing but ill-luck’. Paranavitana arranged with Appuhamy to have the copperplates transferred to the chief prelate of a Buddhist temple in nearby Bengamuva, where a series of protective recitation rituals were performed by Buddhist monks ‘as a method of dealing with the powers unseen’. Only after a year-long stopover at the monastic college of Venerable Vanaratana Thera of Urāpola did the copperplate charters – thoroughly cleansed of the potential for human and supernatural harm – finally make their way to Paranavitana’s hands.

Palpable trepidation – even fear – runs through Paranavitana’s description of how he haltingly facilitates the movement of the copperplates from a rice paddy field in rural Sri Lanka, to the monastic college quarantine base and finally to archaeological offices in Colombo. In the links he sees between exposure to the copperplates and disease and misfortune, one senses foreboding – of danger lurking around the corner as he encounters an artifact possessing a potency that he does not quite understand.

Yet, considering Paranavitana’s response to the discovery as an extension of his interpretive approach to his work is instructive. For Paranavitana, the inscriptions of Sri Lanka’s medieval past were powerful objects that could bend political and social realities to the will of those who mastered the form, language and voice deployed therein. As many recent studies of medieval South Asia have shown, inscriptions were not merely for recording history, but for making history. Traces of this underpin Paranavitana’s understanding of the inscriptions and are surely lost when such documents are flatly read as historical sources, full of dates and events simply waiting to be mined by the historian.

While we might remember this discovery for the effect it had on understandings of medieval Sri Lankan political culture and chronology, we would be remiss to forget the power of the copperplate itself, even in 1949.

That Paranavitana avoided the impulse to read cultural materials for historical ‘facts’ is perhaps less surprising than it might initially appear. His early English education in the south-western port city of Galle was supplemented by study in a traditional Buddhist monastic college, where the curriculum comprised Pali, Sanskrit and Sinhalese reading and grammar; local medicine; calendrical computation; and astrological science. To this day, the halls of Sri Lankan history departments echo with stories of Paranavitana’s breezy proficiency in the languages of the subcontinent and almost preternatural skill in contextualising and interpreting inscriptions. As the narrator of Michael Ondaatje’s novel Anil’s Ghost puts it when describing the epigraphist Palipana, a character based on Paranavitana: ‘Every historical pillar he came to in a field he stood beside and embraced as if it were a person he had known in the past.’

This caricature took on a life of its own in Paranavitana’s latter years, when he wrote fantastical histories of connectivity between Sri Lanka, South-east Asia and the ancient Mediterranean based on ‘interlinear inscriptions’ so small and faintly incised that only he could read and decipher them. Some historians attributed this work to the effects of senility and politely diverted attention to his earlier oeuvre, while others (including former students) publicly denounced him. Debates about the veracity of his sometimes bizarre claims have fallen out of fashion, but some aspects of Paranavitana’s approach are perhaps worth revisiting. As historians, is there value to attending to the total life of inscriptions – to their words, yes, but also their material existence, the historical context for their issuance and the circumstances of their discovery?

Philip Friedrich is a PhD Candidate in South Asia Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Source: History Today Feed