What We Talk About When We Talk About Tunguska - 8 minutes read

Just over a decade after the imperial outpost of Tsaritsyn had become the Soviet city of Stalingrad in 1925, a young writer named Manuil Semenov published a short story, ‘Prisoners of the Earth’, in Young Leninist, the local newspaper of the Communist Youth League. Semenov would go on to have a successful career as the editor of the satirical magazine Krokodil, but the subject of this early literary endeavour was squarely in the realm of science fiction.

In 1908 a massive explosion near the Stony Tunguska River had flattened a vast area of forest in central Siberia. The event remained largely unknown until the late 1920s and early 1930s, when expeditions led by Leonid Kulik failed to find a meteorite or even a crater at the blast site. If there was no meteorite, then what had caused the explosion? Sensationalist coverage of Kulik’s endeavours meant the Tunguska ‘event’ soon acquired international notoriety. Scientists raised the possibility that a comet collision or antimatter might be the cause.

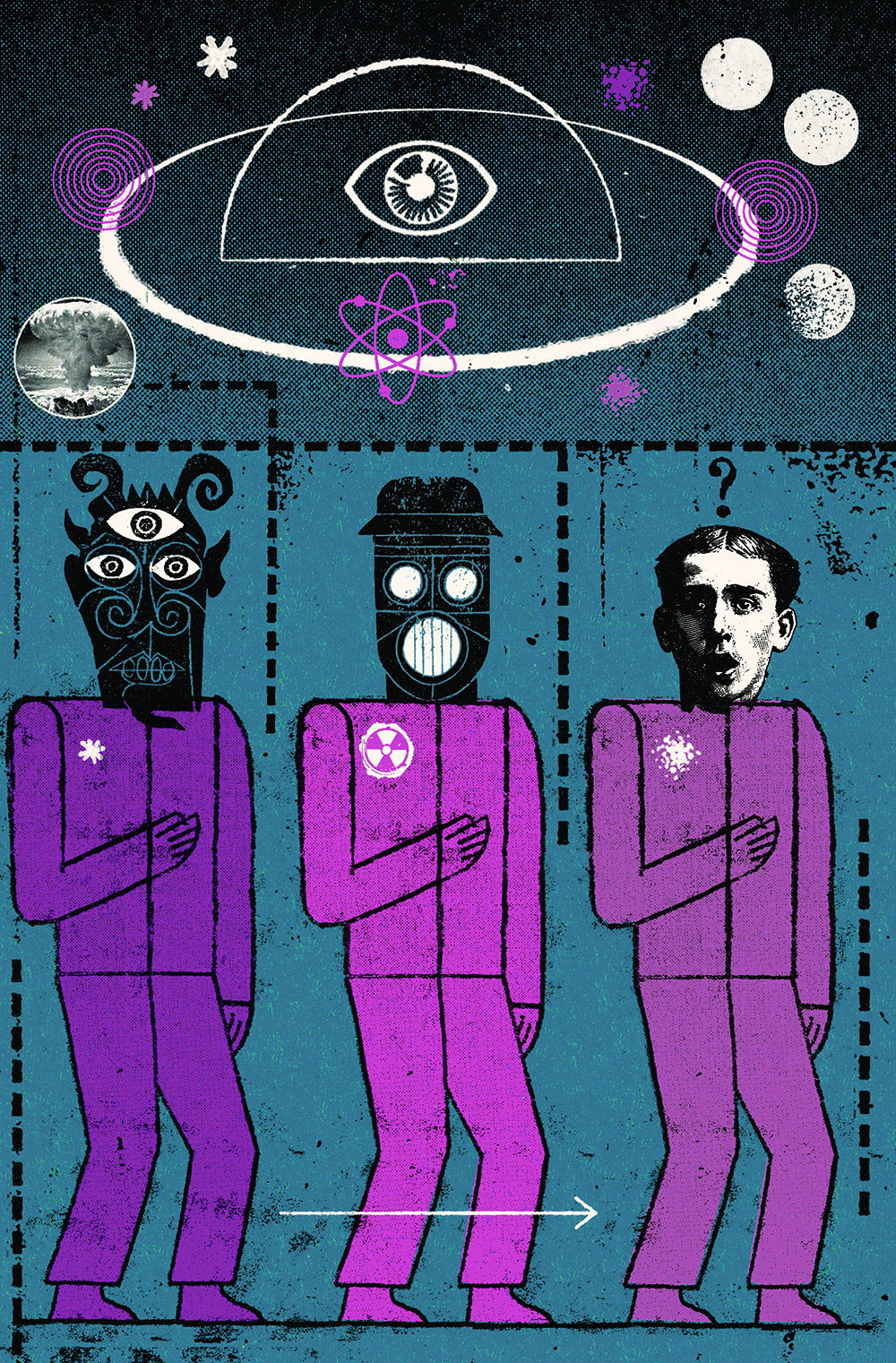

‘Prisoners of the Earth’ described the adventures of a group of researchers who trek out to the site of the Tunguska blast. In the process, they uncover an anti-Soviet plot hatched by a gang of bandits that involves the wreckage of a Martian spaceship which runs on a type of fuel that perplexes the earthlings – and which caused the 1908 explosion. Semenov’s story turned the uncertainties about Tunguska into fodder for fantastic theorising. The event has inspired outlandish hypotheses ever since, and continues to do so on the 115th anniversary of the explosion.

It came from outer space

As a literary work in a provincial newspaper during the height of the Stalinist terror, Semenov’s story received little notice. But it may have been read by another budding writer, Alexander Kazantsev, before he headed off to represent the Soviet Union at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939. After the Second World War, Kazantsev’s name would become synonymous with the hypothesis that a nuclear-powered spaceship had been involved in Tunguska. He claimed that news of the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs had inspired him to concoct a theory that the Tunguska blast resulted from nuclear energy. In late 1945, he consulted with former members of the Kulik expeditions as he wrote ‘Explosion’, a short story which proposed that Tunguska resulted from ‘an interplanetary spaceship that ran on atomic energy’.

The thrill of the atomic age soon caught public attention on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Just months after the publication of ‘Explosion’ in January 1946, the New York Times reported Kazantsev’s fantasy as a genuine proposal about the cause of the blast. This confused coverage predated discussions of flying saucers and UFOs in the international media that would follow in the years to come. Kazantsev began to believe his own hype. He started to write ‘non-fiction’ articles explaining how a crashing nuclear-powered alien spacecraft was the most viable explanation for Tunguska.

With the help of specialists in meteoritics, Kazantsev also staged a performance at the Moscow Planetarium. It began with a lecture by Felix Ziegel, who would later become one of the most prominent ufologists in the USSR, in which Ziegel talked about how a meteorite had caused Tunguska. Then, a staged interruption from a planted audience member turned the performance into a forum for a full airing of the alien hypothesis. Some left the Planetarium convinced by this scenario, which irritated the meteorite scientists in attendance. They derided the show and Kazantsev in the national press. But this only helped to further popularise the idea of alien involvement.

As it turned out, even prominent Soviet officials might have thought that there was something to Kazantsev’s theory. Rumours suggest that in the lead-up to the Soviet Union testing its first atomic weapon in August 1949, the supervisor of the project – the notorious head of the Gulag prison system, Lavrenti Beria – dispatched a team to Tunguska to check for evidence of a nuclear explosion. This could be hearsay, but there is evidence that clandestine aerial photographs were taken of the region in 1949.

Amateur hour

The onset of the Space Age in 1957 with the launch of the Sputnik satellite proved another boon for theorising about Tunguska. It overlapped with a public declaration that the Soviet Academy of Sciences had found iron fragments at the site. Though it was later revealed that these samples had been contaminated through contact with different samples from a meteorite fall in Sikhote-Alin, the Academy initiated a series of new expeditions that eventually concluded that a comet had caused Tunguska. Meanwhile, several groups of educated youths rediscovered Kazantsev’s theories and decided to go in search of extraterrestrials themselves. Their initiative inaugurated an onslaught of voluntary field research undertaken by individuals with a wide range of opinions about what might have been behind the blast.

During their first expedition in 1959, the voluntary researchers of the ‘Complex Amateur Expedition’ recorded heightened levels of radioactivity in the epicentre of the blast. Attentive to any information about nuclear topics in the tense days of the arms race, newspapers broadcasted this find internationally. A detachment of staff from the Soviet space programme that included a future cosmonaut was sent from Moscow with the aim of explicitly searching the area for a spaceship. Even the Academy of Sciences retreated from its initial protests and collaborated with some of the voluntary researchers on fieldwork.

After 1962, professional fieldwork at the Tunguska site wound down and research was left in the hands of the volunteers. By this point speculation about Tunguska had moved beyond the realm of science fiction. Claims about a ball of lightning or plasma circulated on the edge of accepted science. Foreign scientists again proposed their own wild ideas that reflected recent developments in astrophysics. A letter published in Nature in 1973 floated the possibility that a microscopic black hole had triggered the Tunguska blast. If respected physicists could get in on the fun, why couldn’t everyday enthusiasts who had simply read up on the incident? Two of the more interesting and plausible possibilities that emerged evoked a meteorite from Mars and a rare tectonic occurrence.

Proliferating hypotheses in the 1970s and 1980s spurred another attempt at gatekeeping. Even one of the leading outlets of non-conventional thinking about Tunguska, the Soviet magazine Technology for the Youth, resorted to brushing aside many of the new theories that it received as unserious. But the hydra of speculation had been unleashed.

Guardian aliens

Worries about the possible diabolic interference of aliens reached their apex during the Cold War. Abductions, probes and secret cover-ups occupied American imagination, while Soviet visions of UFOs often referenced the explosion. Some of this thinking began to shift with the opening of the Soviet Union during perestroika in the 1980s. A group from Japan received permission to visit the Tunguska site in 1989. They believed that the explosion had occurred when space travellers, who had departed from Japan millennia ago, tried to return home and crashed in the process. A year later the American magazine Fate: True Reports of the Strange and Unknown published a proposal that pinned the Tunguska blast on an experiment by Nikola Tesla with his alleged ‘death ray’. In the post-Soviet period this notion was picked up in Russia and became the subject of numerous articles and books. In the 1990s, it was suggested that aliens living among us had destroyed a cosmic object in the air before it landed, thereby protecting humanity from devastation.

As alternative explanations for Tunguska continued to spread, evidence that it had been a plain old meteorite mounted. Scientists unaffiliated with the voluntary expeditions undertook new fieldwork in the post-Soviet era. By then, meteorite specialists understood that medium-sized fragments of stony asteroids could burst in the air and release a shockwave with enough oomph to level a forest as large as the Tunguska site. The observed impact of the Chelyabinsk meteorite in 2013 offered real-time verification of the existence of such a possibility. In the case of the Tunguska explosion, the absence of remnants might simply be because the tiny material had been buried or washed away before researchers arrived. This deeper understanding of the impact dynamics of near-earth objects (asteroids or comets) does not quite provide a smoking gun, but it does resolve many of the strange circumstances that prompted the search for an alternative explanation in the first place.

No end

Despite this, the Tunguska event continues to inspire fantastic ideas. ‘The genie is out of the bottle’, as a devotee of Kazantsev’s theory once put it. I encountered some of these ideas when visiting the site in 2018 on the 110th anniversary of the explosion. One theory alleged an improbable connection between the explosion and rare green tektite glass found elsewhere in Siberia. In more practical terms, Tunguska gives its name to an anti-aircraft weapon first used by the Soviets in 1982, and deployed again recently in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As we mark 115 years since the mysterious explosion of June 1908, new explanations will continue to reflect the present, as well as concerns about the future.

Andy Bruno is the author of Tunguska: A Siberian Mystery and Its Environmental Legacy (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed