Fu Manchu in Bern | History Today - 5 minutes read

In the 1960s newspapers around the world claimed that the Chinese embassy in Bern had become ‘Red China’s Spy Centre’:

In the gloom behind those shutters, the Red Chinese direct an underground whose agents range from the back alleys of Europe to the steamy jungles of Africa … No. 10 Kalcheggweg not only houses Red China’s embassy in Switzerland; it also operates schools for diplomats, propagandists, spies, saboteurs and subversives.

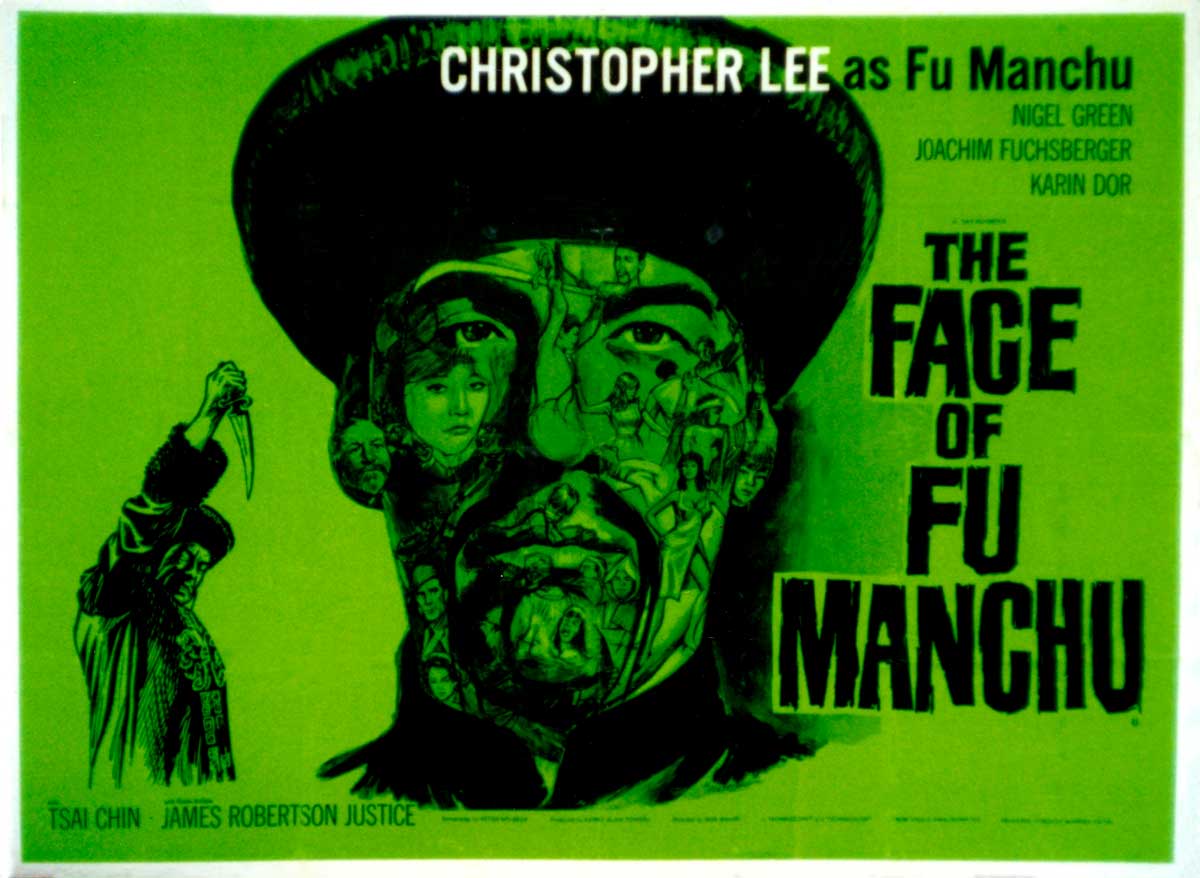

Until recently, China’s networks in Switzerland were unknown. However, thousands of Swiss archival files have now been temporarily declassified, revealing that, while the quote might sound like an excerpt from a Fu Manchu novel, it was not far off the mark.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established in 1949. One year later Switzerland was among the first Western European nations to establish official relations with China; until the mid-1960s, only the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries had diplomatic relations with China, while Britain and China did not establish relations until 1972. Its central location made Switzerland an ideal hub for China’s presence in Europe from the 1950s to the 1970s, for both diplomacy and trade.

Due to Swiss neutrality and the UN’s European headquarters being in Geneva, diplomats from almost every country could be found in Switzerland, making it the perfect location to establish and operate spy networks. China’s diplomatic missions in Switzerland were teeming with spies. Several ambassadors and consuls were intelligence heavyweights, including the first minister and later ambassador Feng Xuan. Wu Jinshi, in turn, joined the embassy in 1956 and became consul in Geneva in 1959. He trained members of the Chinese diaspora from all over Europe as spies and was in charge of a global network of agents and informants. By 1966 the Bundespolizei (Swiss counterintelligence) estimated that more than half of the Chinese officials in Switzerland were either intelligence agents or had intelligence gathering tasks, but there was little they could do beyond placing them under surveillance without potentially endangering Swiss diplomats and citizens in China. As a result, hardly any Chinese diplomats were expelled and only one was refused accreditation as ambassador.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Chinese officials in Bern actively groomed PRC, Republic of China (ROC), Hong Kong and Chinese-Indonesian scientists and science students, establishing intelligence networks that included dozens of Chinese professionals or students of physics, engineering or chemistry from across Europe. Many citizens of the ROC were persuaded to spy for the PRC with offers of passports because they had parents living in mainland China and wanted to move back. Some were told where to work in order to gain specific skills; they were supposed to remain politically inconspicuous and to ‘stay white on the outside but red on the inside’.

China also used the embassy in Bern as a hub for a transnational embargoed goods network, an undertaking that was helped by Switzerland’s refusal to join the NATO powers’ embargo against China during the Korean War. Business people from all over Europe – but primarily from West Germany, Switzerland and Liechtenstein – worked together in the 1950s and 1960s to obtain and ship illegal products such as heavy water, plutonium, or high-speed cameras to China, much to the dismay of European police forces and Interpol, who scrambled to stop these transports once they were discovered. A British Defence Intelligence report from 1965 noted that a ‘highly organised network of embargo evaders’ had tried in 1964 to purchase a high-speed camera that had originally been developed in Britain for nuclear weapons trials. It was eventually tracked down and confiscated in Germany. Many embargoed goods dealers seem like criminal masterminds with long rap sheets for all kinds of nefarious activities. A dealer from West Germany had three outstanding arrest warrants and was suspected of fraud, forgery, theft and impersonating officials. He also had a fake British passport. A Swiss counterintelligence official concluded that he was ‘a rather nasty subject … Whatever he undertakes is likely to be done fraudulently’. While the real extent of China’s successful import of banned material from Europe is unknown, Bern’s embargoed goods network seems to have played a crucial part in China’s production of nuclear weapons.

The Chinese consulate in Geneva and the embassy in Bern also operated a global network of ROC diplomats, who were working either for the UN or an affiliated international organisation. They used their official meetings in Geneva to report to their Chinese handlers. In 1968 the US representative to the UN in Geneva, Roger W. Tubby, claimed that the Chinese consulate’s staff took advantage of UN delegations visiting Geneva, ‘especially Asians and Africans, to make contact with them by inviting them to dinners or lunches’. However, most of China’s UN informants and agents were from the ROC. One of them was Shi Zhengxin, a doctor working for the WHO, who was permanently stationed in Geneva. Shi had been spying for the Chinese for at least eight years before he was expelled in 1966 for forwarding letters and packages from UN diplomats to the Chinese consulate in Geneva. Others were less successful at evading the authorities. At one point, Swiss police observed a meeting between a UN translator from the ROC and a Chinese consulate official which resulted in the diplomat calling for a taxi because the translator wanted to hand over so many documents.

Chinese restaurants in western Europe were also suspected of being complicit in a transnational network orchestrated from Bern. Although a money trail spanning several countries was uncovered, evidence remained murky. Ever since Fu Manchu, Chinese restaurants have been associated with a criminal underworld, although there were only a few cases in which spies or other collaborators were discovered. This did not temper the European public’s appetite for stories of a Fu Manchu spreading his net across Europe, whose helpers sautéd vegetables when they were not involved in criminal activities.

Ariane Knüsel is the author of China’s European Headquarters: Switzerland and China During the Cold War (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed