The ‘Monstrous Birth’ of Lobsters - 10 minutes read

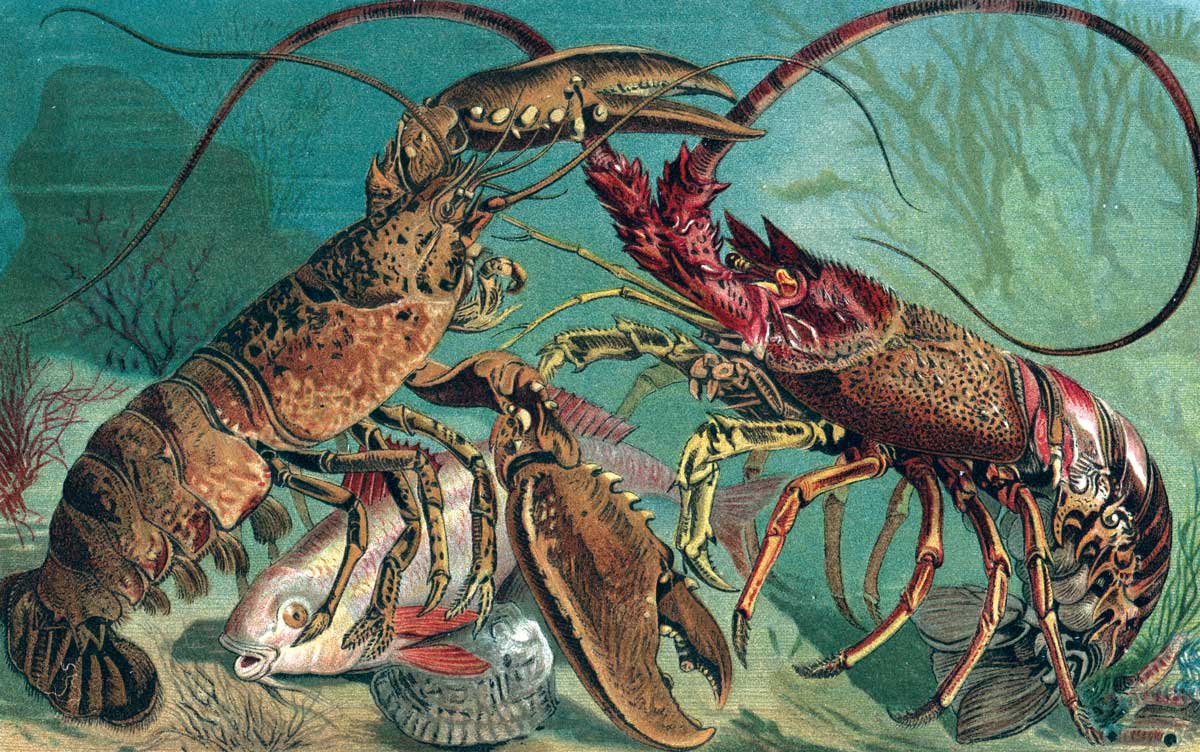

Aristotle was rarely puzzled, but even he had to admit that lobsters were weird. After leaving the court of Hermias of Atarneus in around 340 BC, he had spent several years studying the creatures on the island of Lesbos. He had watched fishermen bringing in their catch, talked with travellers from far-off lands and examined specimens for himself. In fact by the time he left Lesbos to take up a job in Macedon in 343 BC he had become something of an authority on them. With the keen eye for ‘family’ resemblances which was to become the hallmark of his scientific method, he had spotted that, in most important respects, they were no different from any other crustaceans. Like crabs and crawfish, he wrote in the Historia animalium, they have ‘hard and shelly parts on the outside, where the skin is in other animals, and the fleshy parts inside’; they have ‘little flaps’ on their bellies, where the females deposit their spawn; they have two mandibles on either side of the mouth; and they have a peculiar organ called ‘mytis’ or ‘poppy juice’. What made them unusual, however, were their claws. Although plenty of other species also had claws, lobsters’ were completely different. Not only was one of their front claws bigger than the other, but they also had a set of much smaller claws on two pairs of their legs. This was peculiar enough in itself. After all, why did they need six claws, rather than just two? And why in so many different sizes? Strangest of all, however, was what they did with them. Instead of using their secondary claws like the others, lobsters appeared to walk on them.

‘Deformed’

For Aristotle, this was nothing short of bizarre. His whole approach to biology was founded on the idea that nature never did anything in vain. Each part of an animal had a definite function – and its function determined its form. Human feet are flat so that they can be used for walking, fish have flexible tails so that they can swim and so on. By extension, no animal should have anything it doesn’t ‘need’ – or that doesn’t do what it is ‘supposed’ to do. This was where lobsters were going wrong. Any fool could see that the ‘natural’ function of claws was grasping. So why on earth were lobsters using them for walking?

Since nature clearly didn’t ‘intend’ claws to be used like this, Aristotle could only assume that lobsters were ‘pepērōmenos’. As the US philosopher Charlotte Witt has pointed out, this literally means ‘maimed’ or ‘mutilated’; but, in this context, it probably meant something like ‘imperfectly developed’ or ‘deformed’ – in other words, an aberration from the norm.

Lobsters were not the only ones, though. In De generatione animalium Aristotle identified plenty of other animals that were ‘deformities’, too. Like the lobster, some had parts which did not seem to perform their proper function. Moles, for instance, have eyes, but lack the faculty of sight. Others, like frogs and crocodiles, which could live equally well in water or on land, seemed to have parts belonging to two or more species. And, finally, there were those poor beasts that were occasionally born in ‘monstrous’ forms, as if two individuals had fused together in the womb – such as two-headed snakes or five-legged sheep.

Spanner in the works

None of these ‘deformities’ should exist, of course. So why did they? It was a tricky question. There was always a temptation to write ‘deformities’ off as just ‘one of those things’. Monsters such as two-headed snakes were clearly a freak occurrence, which came into being merely as a result of bad luck. It was pointless to ask why they had the features they did: the very randomness of their existence precluded any satisfactory explanation of their form. They just ‘happened’. But the same could not be said of lobsters’ claws. Since lobsters naturally produce ‘deformed’ offspring, their ‘deformity’ was plainly not a matter of chance.

Another possibility was that lobsters’ deformity arose from some hidden necessity. This might seem a little strange at first glance. ‘Monstrosity’ and ‘necessity’ don’t make the most natural bedfellows, after all. But for some sorts of deformity this explanation seemed to work just fine – at least to Aristotle. Take females. Although scholars are divided over how certain key terms should be interpreted, Aristotle appears to suggest that, while female animals are ‘like’ (‘hōsper’) deformed males – since they cannot generate sperm – anyone can see that their existence is necessary for the continuance of their species as a whole. But the same argument didn’t seem to work for lobsters. In fact, it took you straight back to square one. If lobsters’ ‘deformity’ was the result of necessity, what necessity could possibly demand that a grasping appendage be used for walking?

The only explanation was that there was a spanner in the works. Nature was being prevented from running its ‘normal’ course, not by chance, nor from necessity, but because some external or internal factor was getting in the way all the time. But what?

Out of proportion

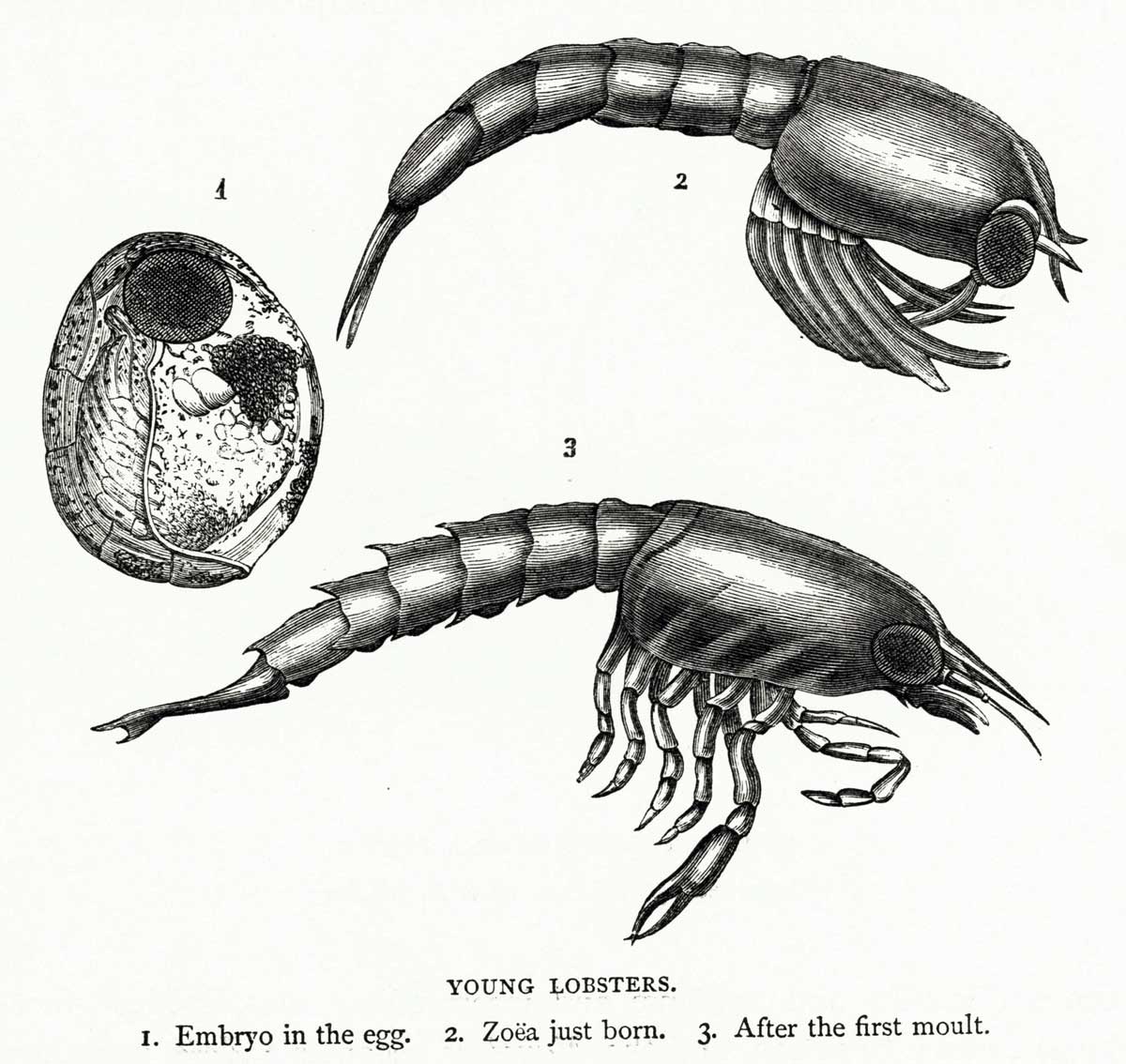

A clue was provided by two-headed sheep. As Aristotle had already hinted, they were the result of a chance mishap, which could only have occurred during gestation. Of course, being freak occurrences, they were nothing like lobsters, each generation of which was more or less the same as the last. But they nevertheless suggested to Aristotle that whatever was going ‘wrong’ with lobsters’ claws was somehow bound up with the reproductive process.

As Aristotle explained, the form an animal inherits from its parents is determined by the interaction of male and female ‘generative residues’. Semen contained within it ‘pneuma’, the ‘breath of life’. This gave rise to a ‘vital heat’, which caused things to grow. When this interacted with the ‘elemental matter’ provided by the female, it catalysed the ‘movement’ necessary to generate a living offspring.

Given that semen provided the ‘blueprint’ and the female elemental matter the ‘materials’, it would be reasonable to assume that deformities must result from some issue with the former. This, at least, was what the atomist Democritus believed. Writing two generations before Aristotle, he had argued that monstrosities occurred when two ‘emissions of semen’ got muddled up in the womb, so that ‘the parts of the embryo grow together and get confused with one another’. But this seemed dubious, to say the least. If Democritus was right, Aristotle argued, we should expect to see no deformed offspring at all when ‘several young are produced from one emission of semen and a single act of intercourse’ – which was clearly not the case.

If deformities did not originate in the semen, the only plausible alternative was that they arose from a combination of male and female residues. It was all a matter of proportion. In order to form ‘complete’ or ‘normal’ offspring, Aristotle argued, semen and elemental matter had to be in proportion to one another. If there was too much semen, for example, or if the semen had too much ‘vital heat’ in it, then it would ‘dry up’ the female generative residue and cause offspring to be deformed. But, if this was the case, what caused the residues to be out of proportion in the first place?

Too much juice

Once again, the answer was suggested by monstrous births. It had not escaped Aristotle’s notice that these happened more frequently in some animals than others. Species which produced more offspring at a time (‘polyparous species’), such as sheep and goats, tended to have more deformed ones. And, in a peculiar twist, those which produced large litters and had lots of toes on their feet – like cats – seemed to produce the most of all.

True, not all the offspring of these species were ‘monsters’, but Aristotle could not help feeling that they were ‘naturally’ predisposed to deformity. All kittens, for example, are born blind. Most overcome this a few days later, but such an imperfection nevertheless pointed to some sort of inherent fault.

This was obviously not down to having many toes. Even Aristotle recognised that was just a coincidence. After all, elephants have five toes and generally only have one child at a time, which is rarely deformed. So it must have something to do with polyparity. Why, then, do some animals have lots of children?

The answer, Aristotle held, was that the parents must simply be producing a lot of generative residue. And this was due to their size – or, rather, their lack thereof. Large animals, like elephants, are so big that most of the food they eat is needed for growth. Only a little bit is left to make residue. Since Aristotle believed that a certain fixed amount of residue was needed to make an (equally large) embryo, this meant that there is generally only enough to produce a single offspring – if that. Small animals, by contrast, can generate a lot more residue. Given that their embryos are also quite small (or so Aristotle thought), this inevitably resulted in a lot more children.

It also meant that the margin for error was greater. Because so much residue was produced, it was more likely that the volume of semen and elemental matter would be out of proportion to one another. This, Aristotle reasoned, was why polyparous animals had so many deformed offspring.

The same logic could be used to explain why frogs and crocodiles have parts suited to living on both land and water. In this case, Aristotle argued, the parents produce more than enough generative residue to make one embryo, but too little for two. The ‘extra’ residue then swooshes around until it forms additional – but unnecessary – parts, thus giving the offspring the appearance of being composed of two or more creatures.

Crucially, it also explained why lobsters walk on their claws. Although Aristotle is frustratingly terse about this subject, Sophia Connell has argued that the parents presumably generate enough residue to create a lobster embryo, but fail to produce ‘enough … to complete’ the lobster’s body. As a result, the offspring have one pair of functional claw and an additional two pairs of half-finished nippers, which the poor beasts have to make the best use of they can by walking on them.

Weird is wonderful

Most, if not all of this, has since been proved wrong. But it was nevertheless an ingenious solution to a seemingly intractable problem. In that it was based on a combination of observed similarities and logical deductions, it showcases the heuristic power – if not the accuracy – of Aristotle’s method. As such, it goes some way to explaining the hold his biological works were to have on scientific thinking until as late as the 17th century.

Yet Aristotle’s adventures under the sea also point towards something more fundamental. The only reason lobster claws were such a problem in the first place was his insistence on an arbitrary – but rigid – notion of ‘normality’. Given his method, it was an understandable assumption to make. Perhaps it was even ‘natural’. After all, which of us does not instinctively appeal to the ‘normal’ when confronted with something unexpected? But, as Aristotle found to his cost, nothing is more guaranteed to obscure the wonderful variety of nature – or cause us more distress and confusion. So to Hell with the normal. Weird is wonderful.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, is now available in paperback.

Source: History Today Feed