Disraeli or Churchill? | History Today - 8 minutes read

In March 1846, at the height of the destructive debate over the repeal of the Corn Laws, the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, rounded on his chief tormentor, Benjamin Disraeli, and asked how it was that if, as Disraeli claimed, he so disapproved of the Government, he had solicited a place in it? Taken by surprise, Disraeli resorted to default mode: he lied. Disclaiming that thwarted ambition had played any part in his rebellion against Peel, Disraeli denied seeking office. Historians have speculated on Peel’s motives in not acknowledging the lie, but for our purposes here, what matters is the ease with which Disraeli told a lie which suited him.

Few believed him. Disraeli was widely distrusted. While some of the distrust came from the strain of antisemitism which continues to disfigure public life, most of it came from his character and his record. He was a journalist and a bestselling novelist whose approach to politics was marked by a cavalier way with the truth. He was known to be in debt and his personal life was said to be dubious; he had, after all, married the widow of a fellow MP in order to be able to benefit from her income. The man was, in short, a colourful rogue. It did not stop him from being a winner. Just as Gladstone accused Disraeli of debauching public life and deplored his habit of playing fast and loose with the truth, so do Boris Johnson’s critics level similar allegations at him; but in both instances the voters seemed less concerned.

Living by the pen

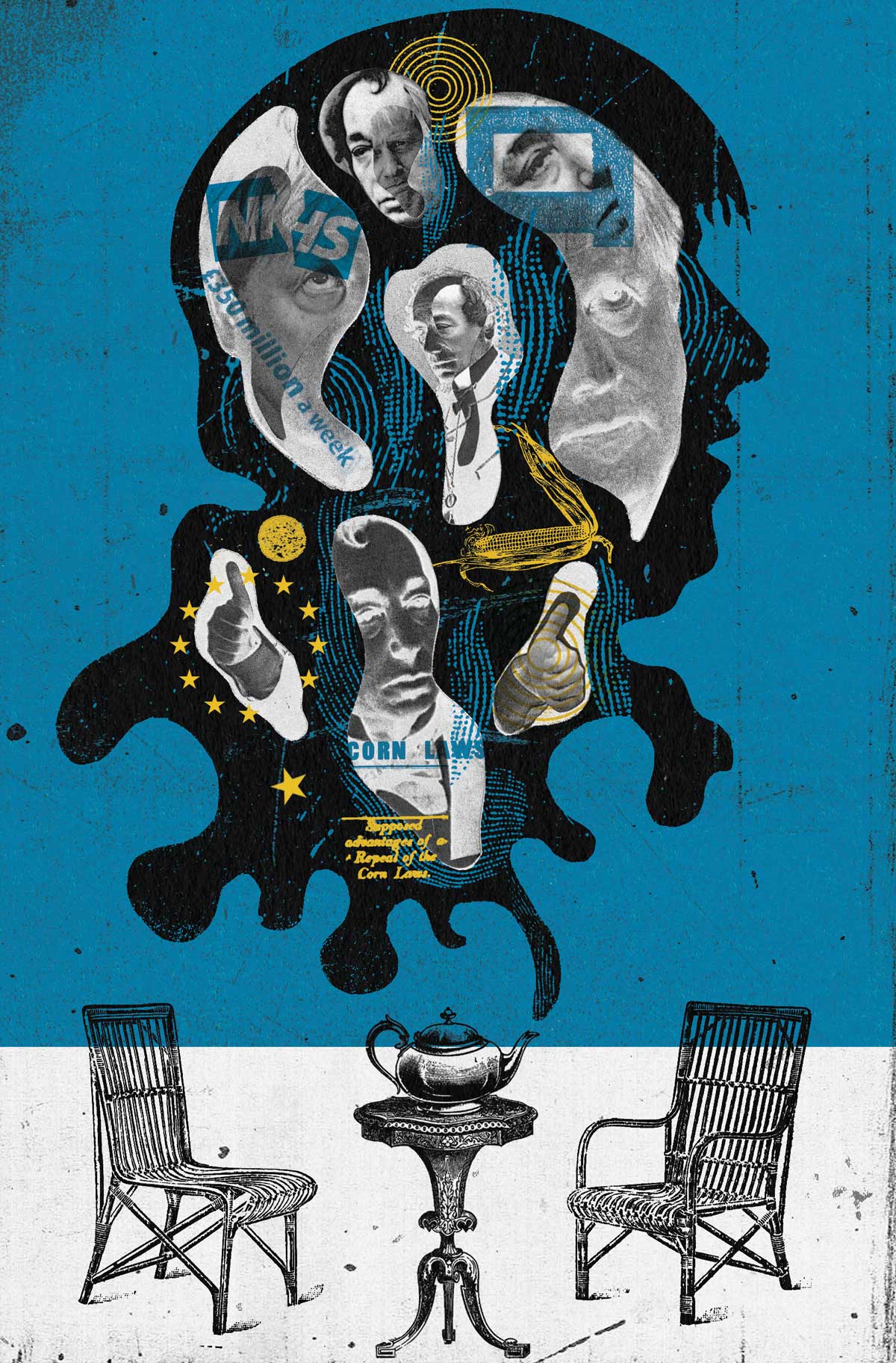

Disraeli was one of only three British prime ministers who have earned a living from their pen and although the third of them, Boris Johnson, likes to compare himself with the second of them, Winston Churchill, the comparison with Disraeli is the more illuminating.

In retrospect, Disraeli’s immediate Conservative heirs assigned to him the place he had sought – that of the founder of ‘One Nation’ Conservatism – or, as his self-proclaimed heir, Lord Randolph Churchill called it, ‘Tory Democracy’. Historians, being studious and serious people, have expended a great deal of time and energy trying to define this phenomenon, but they should have taken Randolph’s own definition seriously – it was a way of getting the democracy to vote Tory, which meant that it was ‘mostly opportunism’.

Unlikely alliance

In this sense, Johnson is a worthy successor to both Randolph and Disraeli. Disraeli had no previous connection with those ‘stern unbending Tories’ who had been murmuring against Peel since he betrayed them (as they saw it) over Catholic Emancipation in 1829, but it suited his ambitions to act as their spokesman in the 1840s; lacking in oratorical talent themselves, they reluctantly embraced Disraeli. A similar marriage of convenience occurred in 2016, when the Brexiteers and Boris Johnson joined forces.

Johnson’s critics, like Disraeli’s, could plunder the written record to find examples of their changing their minds, but in both cases, this was priced into the offer. In 2016, as in 1845, there was a trade-off between inconsistency and expediency. Charisma is a rare quality in politics. Those who have it are forgiven much, to the fury of the more sober-sided who feel it is ‘unfair’. Just as Disraeli drove Gladstone to righteous anger, so Johnson’s critics bridle at the way in which his private life appears not to be the major problem they think it should be.

Napoleon used to ask of his generals not whether they were any good, but whether they were lucky; Disraeli and Johnson rode their luck. Becoming prime minister in time to encounter a major pandemic may mean Johnson’s luck has run out, but surviving the disease, and thereby avoiding George Canning’s fate, suggests fortune may still be with him.

It would be wrong to say that Johnson, like Disraeli before him, is without principles, but he understands that political realism will dictate what is possible – and determining the latter is the art of the leader. Like Disraeli, Johnson does not command detail, something which historians who do command it, and politicians who imagine it to be important, find deplorable. But as the singular case of Johnson’s predecessor, Theresa May, shows, a command of detail by itself can be fatal – without vision the political party perishes.

Rhetoric matters

Both Disraeli and Johnson are criticised for ‘empty rhetoric’ and it is always easy (which is why it is done so often) to write off rhetoric as ‘mere words’. Yet, as Barack Obama, Churchill and others show, it matters. You can produce a fine manifesto promising free stuff for all, but if the salesman lacks credibility, it simply becomes the ‘longest suicide note’ in history. The best political rhetoricians keep it simple, a truth exemplified by three of the finest modern orators, Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and Obama. But what matters in a crisis is the ability to radiate optimism.

And it is here, finally, that Johnson’s comparison with Churchill is apt. Churchill’s decision to fight on in 1940 was illogical, but optimistic. Though he claimed the United States was about to enter the war, it wasn’t, and although he claimed British air power could deliver victory, it couldn’t. Most sensible people knew that, but Churchill was not a sensible person, he was a romantic and, in rallying the nation to its ‘finest hour’, he helped create the victory which his instinct knew was there.

Johnson operates on the same wavelength. Like Disraeli, who in 1874 delivered a Conservative victory which all the wiseacres had declared to be impossible, Johnson confounded his critics in December 2019. Was he evasive about detail, did he duck and dive to avoid scrutiny? Yes, because like Disraeli and Churchill, Johnson did what was necessary to achieve victory; everything was subordinate to that task. Winning an argument is all very well, but unless that brings you to power it is a pyrrhic victory.

To govern is to choose, de Gaulle said. Johnson’s rhetoric shows he realises the nature of the choices he has to make, but only time will show whether he can make them. There is evidence that he is able to do this, both personally and politically. Johnson, Disraeli and Churchill all earned a good living away from politics and Johnson is the first prime minister since Baldwin to sacrifice a larger income for the sake of office. Unlike his two peers, Johnson also has experience of local government. He was that rarest of Tories in the noughties, one who could win over voters in London; he has shown the same skill in exploiting Brexit in areas of the country which have not voted Conservative in living memory. Furthermore, Johnson has shown that he can compensate for his weaknesses by choosing some subordinates wisely. Disraeli compensated for his lack of command of detail by employing ministers, such as Richard Cross and the Earl of Derby, who were in complete command of their brief. Johnson did the same as Mayor of London and is trying to repeat it as prime minister – Rishi Sunak, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, is the best example so far.

One nation or two?

And then there is the issue of ideology. The persistence of the legend that Johnson’s stance on Brexit marks him out as an extreme right-winger is evidence more of his opponents’ outrage than it is an accurate assessment. Johnson was one of the first Conservatives to come out in favour of gay marriage and he is very plainly a social liberal, and not only in his personal life. He is the first Conservative leader since Ted Heath in the 1970s to favour state intervention and higher public spending; were it not for Europe, Michael Heseltine would be declaring Johnson as his worthy successor.

In Thatcherite parlance Johnson is a ‘wet’. In so far as a One Nation Conservative looks toward healing the rift between the ‘Two Nations’, that is the rich and the poor, Johnson’s rhetoric places him firmly in that tradition. To those who, rightly, argue that tells us nothing about what he will do, one might suggest that the reality of opportunism points toward him wanting to put the rhetoric into action, because it is the way to hold onto the Labour seats he won in December 2019. Just as the Tory diehards who had supported Disraeli because of his stance over the Corn Laws turned against him because he was liberal on parliamentary reform, so might the party’s Thatcherite establishment find Johnson a hard pill to swallow. What matters to him is power, not ideology or consistency.

We can see in his reaction to the coronavirus pandemic that Johnson will adapt himself to whatever is required. Not only has he put his own libertarian instincts aside, albeit reluctantly, he has announced the largest government intervention in the economy since the Second World War.

Ruthless pragmatism

Thatcherite individualism is set aside as Johnson shows himself the heir to Rab Butler’s epigram that politics is the art of the possible. Just as he caught the Brexit Party’s Nigel Farage bathing and stole his clothes, now he has stolen those of the former leader of the Labour Party. The pragmatism is ruthless. The question of whether it will be effective takes us back, though to the prime minister’s favourite comparison – Churchill. If he fails to rise to the occasion it will be Neville Chamberlain with whom he ends up being compared. Who then will be his Churchill?

John Charmley is Pro-Vice Chancellor of St Mary’s University, Twickenham.

Source: History Today Feed