Misery in the Head | History Today - 17 minutes read

Migraine affects one in seven of the world’s population – approximately a billion people. The World Health Organisation calculates it to be the seventh most disabling among all global diseases, more prevalent than diabetes, epilepsy and asthma combined. Virtually everyone will live with, work with, be related to, or be friends with someone who has migraine. But how, over the centuries, have people interpreted, explained and treated this disease?

What is migraine?

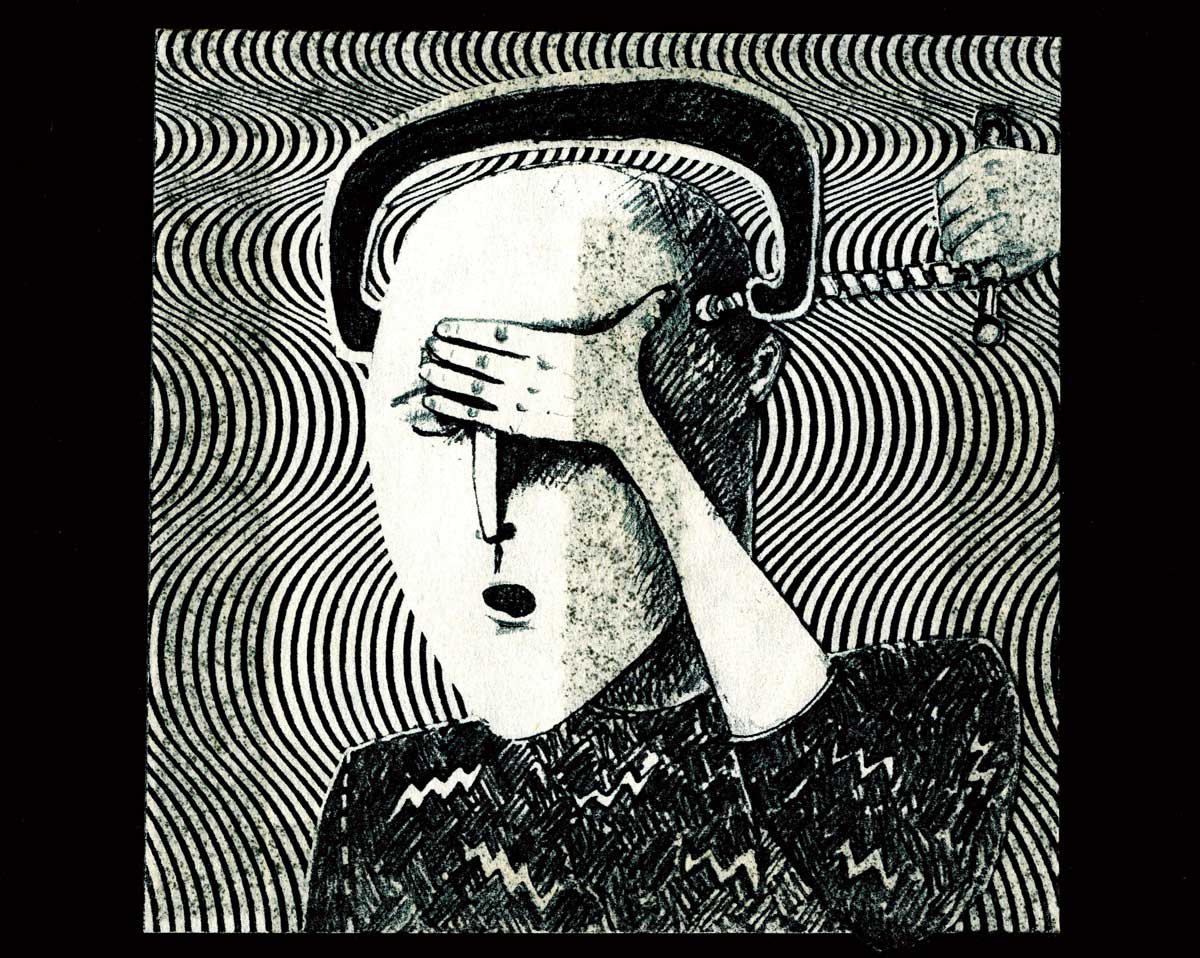

The writer and broadcaster A.L. Kennedy has described migraine as ‘a ghost, it’s a gaoler, it’s a thief, a semi-perpetual dark companion’. Rudyard Kipling, on the other hand, wrote in a letter that it was ‘a lovely thing’, though it divided him in two: ‘One half of my head … throbs and hammers and sizzles and bangs and swears while the other half – calm and collected – takes notes of the agonies next door.’

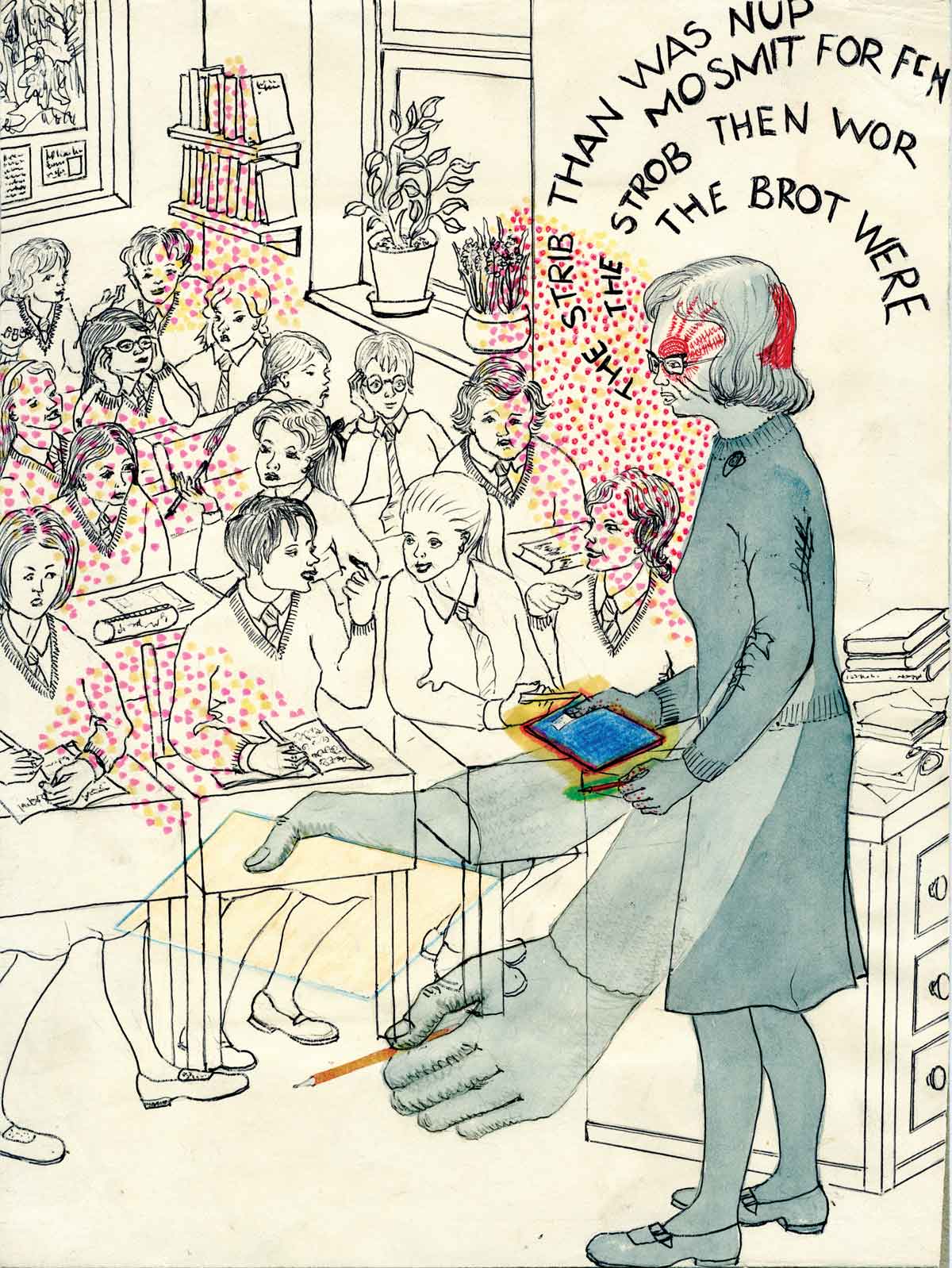

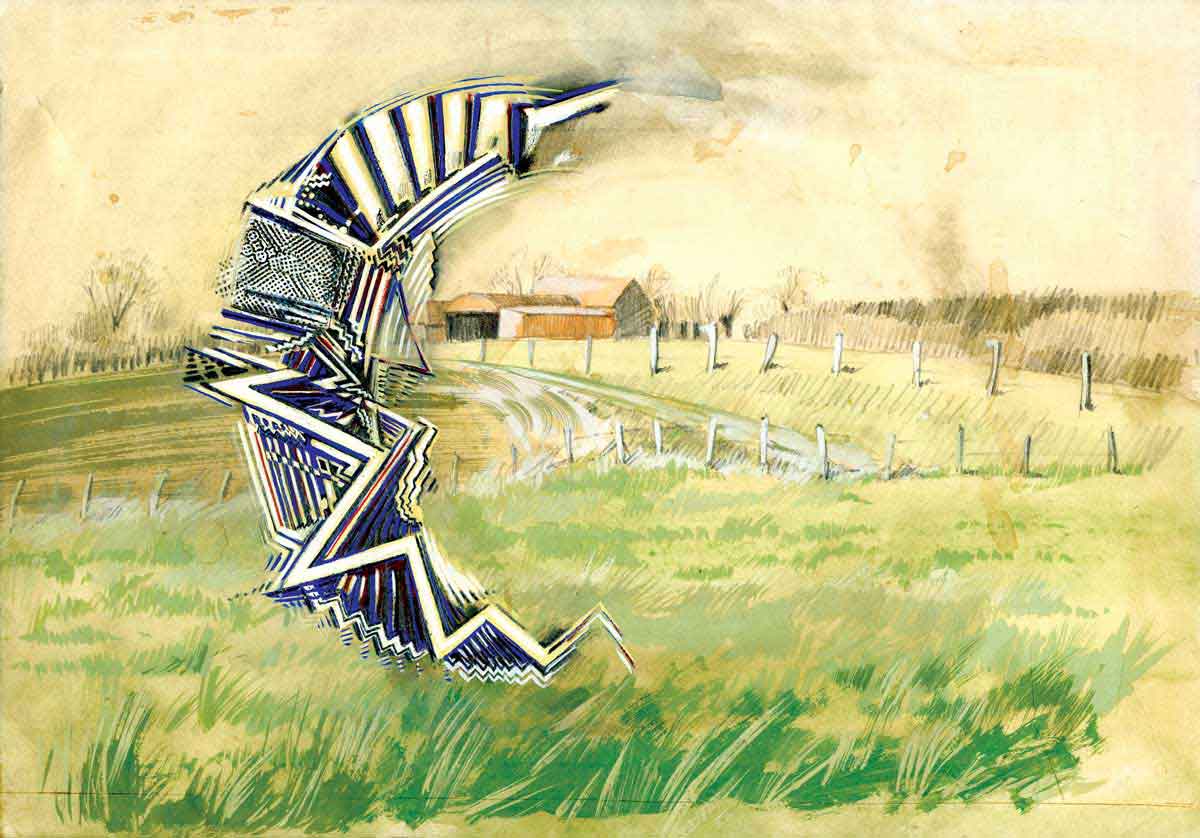

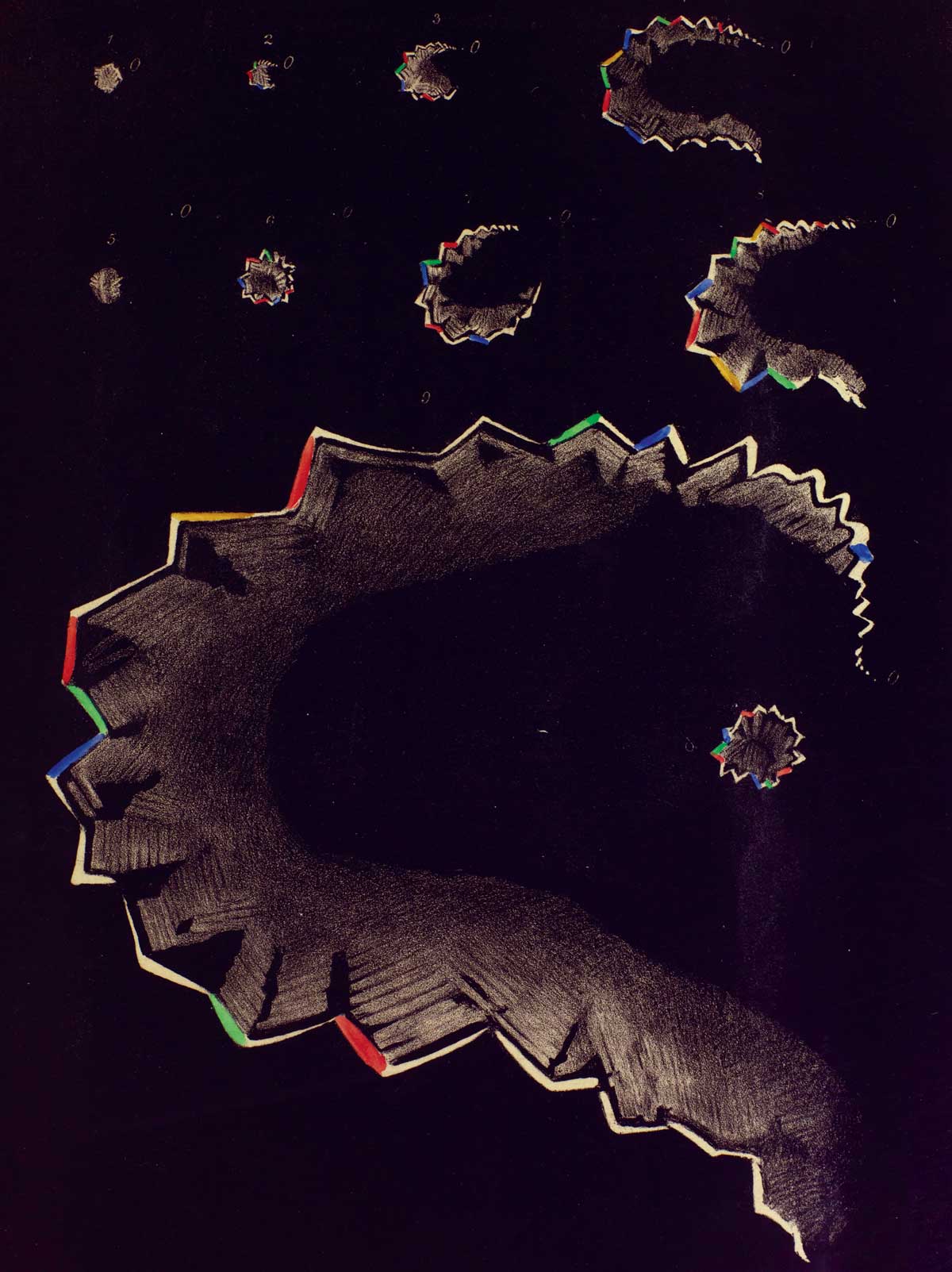

There are many types of migraine. Migraine without aura is most common. Characterised by severe pain, often in one side of the head, attacks can last from a few hours to three days and often include nausea and vomiting. Before and during a migraine attack, many people experience various other symptoms, such as tiredness, emotional disturbance, poor concentration and sensitivity to light or sound. Migraine with aura involves additional neurological symptoms, most commonly a visual aura lasting between five and 30 minutes. Many people see a C-shaped zigzag pattern that spreads across the field of vision. Aura can affect any of the senses, manifesting as vertigo, tinnitus, reduced hearing, pins and needles, whistling sounds, numbness or speech disturbance. On average, migraine sufferers experience one or two attacks a month, but around two per cent of the world’s population has chronic migraine, classified by the International Headache Society as headaches that occur for 15 or more days per month (of which eight are migrainous), for three months or more.

Migraine affects women two to three times more than men, is common among children and seems to be more prevalent among people with low socio-economic status. As well as the pain and discomfort of each attack, the cumulative effect of migraine can bear on all aspects of daily life, affecting relationships with family, partners, friends and work. We know that migraine involves nerve pathways and chemicals in the brain and it seems likely that the headache pain comes from neurogenic inflammation. But much remains unknown about migraine, including its cause and the extent to which antimigraine drugs can access the brain. It is this uncertainty which makes understanding migraine’s history so important.

A migraine by any other name

For nearly 2,000 years, people have talked about a disorder called migraine. In the second century ad, the Roman physician, surgeon and philosopher Galen used hemicrania to describe a pain that affected half the head and was caused by rising vapours from bilious humours in the stomach. Through translation and use, Galen’s term spread. We find emigranea in Latin and Middle English, migran in medieval Welsh. The early modern period saw many variations on the English ‘megrim’ or ‘meagrim’. Galen’s term also provides the common root for migraine in a variety of languages, including migräne (German), migraña (Spanish), migréna (Czech and Hungarian) and, of course, the French migraine.

While Galen’s description remained influential, the symptoms that people understood as migraine changed over time. In the early medieval period, for example, sensory symptoms appeared in discussions of migraine, before slipping out of common use until late 18th-century European writers incorporated them once more. The significance of gastric disturbances has waxed and waned, depending on the changing medical frameworks that best seem to explain migraine at any particular time. As the meaning of ‘megrim’ evolved during the 17th and 18th centuries under the influence of nervous theories of disease, the name ‘sick headache’ or ‘bilious headache’ arose to re-emphasise the relationship between the key symptoms of head pain and nausea.

In the 1870s, the Cambridge physician Edward Liveing attempted to revive the use of the English name for the disease in his influential text On Megrim, but by then the majority of his compatriots preferred the French term migraine, reflecting the decisive influence of European medical thought. Migraine has also been associated with many other disorders, from the 17th-century humoral concept of rheum, to vertigo, epilepsy and hysteria, to chronic daily headache, cluster headache and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia in our own time.

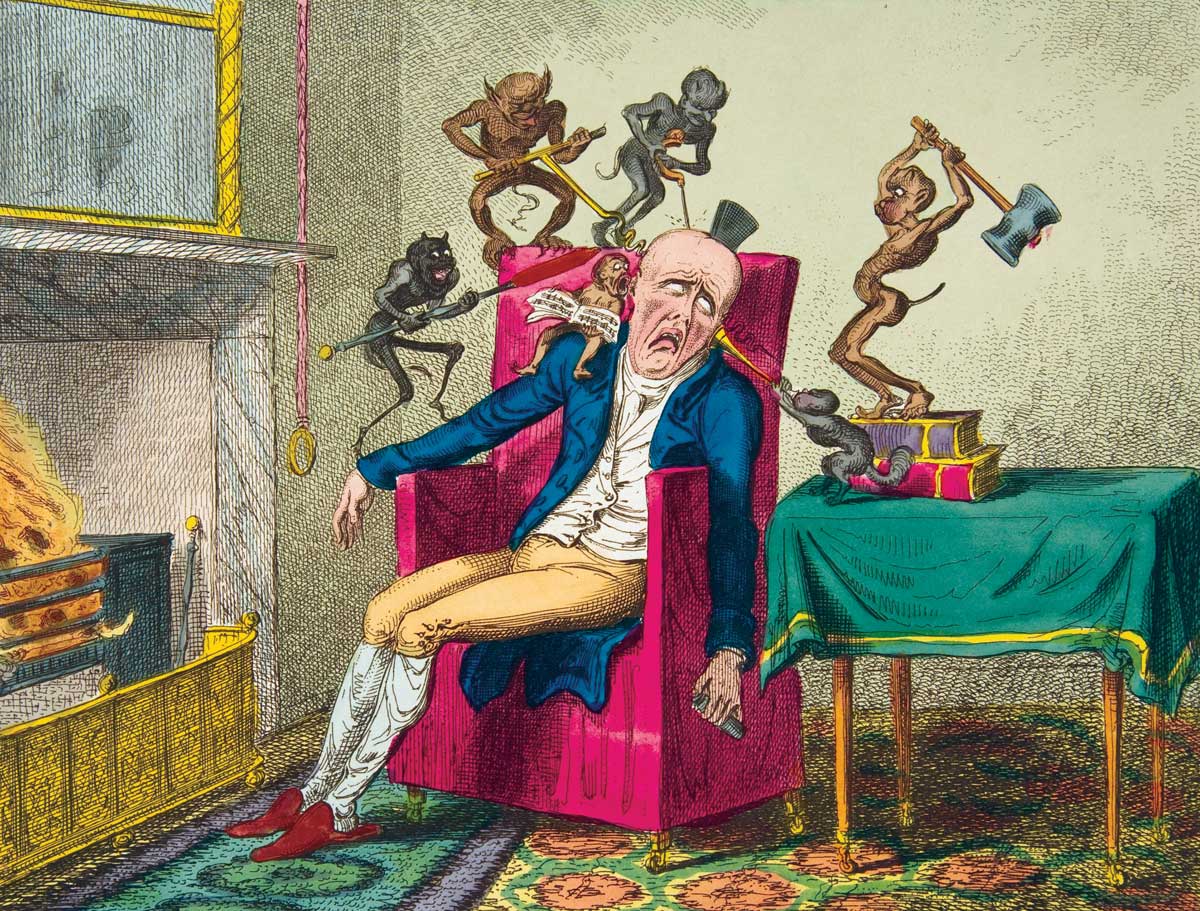

Hammers in the head

I have often been asked how long people have known what a migraine was. Answering this question is not simple, but it gets to the heart of an issue that historians and historically minded clinicians have long debated: what is it that we are looking for when we write histories of disease, illness or medicine? Does ‘diagnosing’ historical figures using our own – sometimes very modern – biomedical categories tell us anything about history? Figures such as Julius Caesar, Thomas Jefferson, Hildegard of Bingen and Pablo Picasso have all been diagnosed more or less convincingly with migraine from the vantage point of the 20th and 21st centuries. But, if we decide not to take this approach, then how do we respect and contextualise past knowledge on its own terms, however inaccurate or strange that knowledge might now seem?

In sources that span hundreds of years, I have been repeatedly struck by how vividly people have described the quality and severity of the pain associated with a disorder they called migraine and how precisely they have accounted for its force in the body, using the explanatory frameworks available to them. There is, for example, a remarkable description of migraine in the 13th-century encyclopedia De Proprietatibus Rerum (‘On the Properties of Things’), compiled by the Franciscan monk Bartholomaeus Anglicus (Bartholomew the Englishman). Emigranea was a ‘most grievous’ ache that, for the patient, felt like ‘there were beating hammers in his head’. One would be unable to tolerate noise, voices or light. The head pain seemed to pierce and prick, burn and ring, its cause identified as ‘choleric smoke, with hot wind and windiness’.

It is difficult to imagine a better evocation of the burning, throbbing, internal turmoil of a migraine attack than this. Nevertheless, Bartholomaeus reassured his readers that emigranea could be quickly taken care of using either bloodletting or scarifying (making shallow cuts) in the shins, to draw the humours, fumes and spirits away from the head. After bleeding, the patient should be purged, then lukewarm water should be poured over the head, hands and feet to open the pores and let the fumes evaporate. Bartholomaeus’ ideas were not new: his knowledge of emigranea came – as he acknowledged – from Constantine the African’s succinct medical handbook Viaticum, from the late 11th century. Viaticum was itself a translation from the Arabic of a 10th-century medical work by the physician Ibn al-Jazzar.

We find another powerful description of migraine at the turn of the 16th century. ‘My head did ache last night / so much that I cannot write today’, wrote the Scottish poet William Dunbar as he addressed his patron, James IV of Scotland, the morning after a migraine. In a three-stanza poem called ‘On His Heid-Ake’, Dunbar described how the migraine was so disabling, the pain piercing his brow like an arrow, that he could scarcely bear to look at the light. In the second and third stanzas, Dunbar evoked a sense of the migraine’s ‘postdrome’, or aftermath. Although the pain had gone the next morning, he felt ‘dulled in dullness and distress’ and could find no words to write. Dunbar’s migraine poem is a personal, reflective piece, a plea for forgiveness for the failure to entertain his royal master. It is also an important historical document, because it so clearly shows how Dunbar understood a migraine attack felt and because it included sensory symptoms such as an aversion to light and inability to think.

Examples such as those provided by Bartholomaeus Anglicus and William Dunbar help to show that the long history of migraine is much more than a list of treatments and medical theories, but they are also unusual among classical, medieval and early modern sources, which are rarely framed around the lived experiences of individuals. It is during the 17th century that personal correspondence and casebooks begin to provide us with substantial evidence about how people with migraine interacted with physicians and, in particular, with the perspective of women. Remedies from early modern recipe collections – many of which were compiled and shared by women – reveal the personal, intellectual and social networks that people with migraine could draw on for information, support, advice and relief.

Jane Jackson’s recipe book, dating from 1642, is a wonderful source for contemplating what kind of disease early modern people thought migraine to be. Jackson included no fewer than six separate entries for ‘Migrim in the Head’ in her collection. The first recipe was quick, cheap and simple: first, pound together the two main elements of houseleek and garden worms. These should then be mixed with fine flour, the paste spread onto a fine cloth and laid over the forehead and temples. Assuming that the common plant houseleek was readily available, the recipe would take, at most, a few minutes to prepare. The second remedy in Jackson’s collection replaced the flour with vinegar, to make a plaster to be laid on the nape of the neck. The simplicity of these medicines, as well as the speed and ease with which they could be prepared, suggests treatments intended to be made when needed, perhaps frequently. Later recipes in Jackson’s book became more complex. One gave much more specific instructions for collecting the worms: they must be gathered in the morning and left to stand until late afternoon.

Then they had to be taken out one by one, put into a second vessel with a good piece of rye bread and finely pounded together. The paste should be wrapped in a linen cloth, bound to the patient’s temples before going to bed and left all night. Jackson explained that the remedy was not expected to cure straight away; it would perhaps need to be applied four or five times before the head would ‘be whole’. The length of time that the remedy took to produce was appropriate for an illness expected to last for several days. It would be easy to dismiss the use of earthworms as ridiculous – but there was a clear logic at work here. Another 17th-century collection of recipes owned by Elizabeth Sleigh and Felicia Whitfield provides a common-sense explanation: creatures such as earthworms and earwigs, which in life existed to deal with rotting and putrefying matter, could be used in medicine to counteract similar processes in the human body.

The fifth recipe in Jackson’s book required equal portions of many ingredients, including frankincense resin, mastic, turpentine, galbanum, olive oil, linseed powder, laurel, anise powder and cumin. These must be mixed together and laid into a cap of leather, bound tightly round with a linen cloth. It would take planning, knowledge and money to gather so many elements. This, and the requirement for a leather cap, indicate that such a medicine was understood as an investment, but one that would pay off, Jackson explained, because the medicine would last for 20 years. The range of remedies in Jane Jackson’s book, from those easily memorised and made up in minutes to a more sophisticated medicine that would give service for decades, provides strong evidence that 17th-century understandings of migraine encompassed a spectrum from occasional acute attacks to a chronic illness.

Migraine martyrs

Throughout the early modern period, there is evidence that migraine affected the lives of people across the social spectrum. In addition to herbal remedies or bloodletting, 18th-century commercial sellers offered pills and powders, tonics and tinctures. But the classical idea of migraine as a humoral disorder defined by pain in one side of the head was losing ground. ‘Megrim’ was becoming a less certain concept – it could be more of a fuzziness, or a sensorial disturbance related to vertigo. This was a nervous complaint that could be precipitated by an emotional event such as grief, caused by errors of diet or lifestyle. It seemed to affect particular kinds of people. Although medical interest in migraine began to grow across Europe in the 18th century, it is in this period that we first find migraine – and those experiencing it – being dismissed, ridiculed and belittled.

During the 19th century the presence of poor, working-class patients in medical institutions gave physicians access to a new sort of patient and prompted new investigation into migraine’s causes, as well as experiments in treatment. Moving away from humoral explanations, which focused on the character and location of pain, physicians based new ideas on the presumed cause and physiology of migraine pain in the body. In so doing, they increasingly made assertions about the gender and class of people subject to migraine and other headache conditions. As women, and especially lower-class mothers whose minds and bodies had been weakened by daily toil, disturbed sleep and insufficient nourishment, came to be seen as migraine’s ‘martyrs’, physicians became more confident in linking migraine to hysteria, epilepsy, reproductive problems and insanity. Migraine was rapidly being transformed into a woman’s problem.

Researchers keen to theorise about migraine took advantage of the availability of inpatients in specialist settings. In 1871, the Annual Report of the Sussex County Lunatic Asylum recorded the assistant medical officer’s trials of Cannabis indica (Indian hemp) as a potential treatment for migraine. Richard Greene’s experiment brought together changing ideas about the brain, concerns about the professional status of asylum medicine and attempts to find new pharmacological treatments for a range of mental and neurological illnesses. Cannabis promised to be a gentler remedy than strong narcotics like belladonna (deadly nightshade) and opium, perhaps even to be suitable for children.

In 1860, the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic opened in Queen Square, London. With eight beds for women, its aim was to provide a less stigmatising alternative care facility to a lunatic asylum, for patients with chronic neurological conditions such as paralysis and epilepsy. The London Hospital catered to patients from poorer backgrounds who would be unable to pay for medical treatment in a private establishment. The Hospital’s casebooks attest to the unpredictable nature of chronic illness in general and the serious effects of migraine on working lives in particular.

Annie, a 32-year-old butcher’s daughter from Dorset, admitted to the London Hospital in 1899, explained she could tell a headache was coming on when black dots danced in front of her eyes for a day or more. Pain nearly always attacked the right side of her head and usually began in the morning. For two years, Annie had experienced persistent pain on the top of her head, which felt tender under pressure and was worse on some days. Now the headaches came every week and lasted over two days.

Annie’s case notes record the many ways she had tried to treat her own migraine, including tonics, quinine, phenacetin and bromides. Until recently, two 15-grain powders of antipyrin would stop the headache and had worked better than anything else. Eleven days after her admission to the London Hospital, she experienced a vertical ‘thumping pain’ up the right side of her face and was sick in the night. Put on a diet of milk, eggs and bread, she felt better the following day. But then Annie came down with influenza. For two weeks she had a constant headache, never free from pain for more than five minutes. Every morning she had ‘nettle rash’ on her arms, legs and neck. Digitalis was added to her night-time medicine and she began to sleep better.

During her stay as an inpatient, Annie received an astonishing array of pharmacological substances and experimental treatments. The physicians began with chloralose, an anesthetic and sedative. The following day she was given a mixture of diluted phosphoric acid, liquid strychnine, liquid trinitrine and tincture of gelsemium. This combination is significant, because it is an early version of what would become one of William Gowers’ most famous legacies, a migraine treatment known as Gowers’ Mixture, which remained in use by GPs until the 1970s. Two days later, Annie was prescribed 15 grains of antifebrine, a treatment for fever and pain. Over the next few weeks she was also dosed, in various mixtures, with calomel (mercury chloride), potassium bromide (an anticonvulsive and sedative often used for epilepsy), brandy, migranin (a preparatory medicine), more trinitrine, morphine, chloral (a sedative with hypnotic effects), senega (a stomach irritant), antipyrin (a painkiller known to cause rashes and cyanosis), cannabis tincture, phenacetin (another painkiller) and the potent plant extracts digitalis and belladonna. Annie also took exalgine, a substance often prescribed for neuralgia and migraine, the safety of which had been much debated during the 1890s, after several cases of poisoning.

In late May, Annie was discharged, after becoming ‘mentally affected’ for the previous three or four days. Imagining that other patients were talking about her and discussing her private affairs, she had also taken a ‘strong dislike’ to the night nurse and night sister and seen ‘funny wriggly animals round the bed’. Lamenting that their patient had previously been of ‘a particularly nice disposition’, the physicians discharged her. It is hard not to conclude that the change in Annie’s personality must have had something to do with the cocktail of drugs that had been administered over the previous six weeks. Neurological laboratories and hospital wards in places like London’s National Hospital have been the crucible for some of the most advanced neurological breakthroughs in modern medicine, but cases such as Annie’s remind us that medical power and authority are not achieved without human cost.

History, legitimacy, advocacy

A key issue in modern migraine medicine is a situation the American sociologist Joanna Kempner has termed migraine’s ‘legitimacy deficit’. Despite being an undeniably real disease that affects around one in seven of the world’s population, migraine is globally under-funded, under diagnosed and under-treated. This situation has much to do with the assumption that migraine is primarily associated with women, an idea that, as we have seen, only became common in the 19th century. Looking further into the history of migraine shows that our own failure to take migraine seriously is by no means a historical constant. In fact, a great deal of evidence suggests that before then, migraine had been taken seriously for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

It is tempting to dismiss the world view behind old medicines – bleeding points, worm-paste plasters, herbal preparations. But this history has shaped our knowledge about the disease, our changing attitudes towards people who have migraine and the measures we take to address their pain. Appreciating that there is a long history for migraine pills and potions is important, because it remains the case that millions of people with migraine are still unable to access effective, affordable medicines. Comprehending how historical ideas and practices have changed, and the logic behind them – especially when they seem alien to us – reminds us, and perhaps gives hope, that our own efforts to understand and treat this extremely common disease will also be bettered.

Katherine Foxhall is the author of Migraine: A History (Johns Hopkins, 2019).