Breathing Easily | History Today - 5 minutes read

The ancient workplace was extremely hazardous, its conditions causing health problems from callouses and scars to permanent deformities or other, less immediately visible, issues, such as breathing problems. Despite the absence of the modern understanding of health and safety, or even basic principles of hygiene, the people working in it recognised the need for protection, which they managed using a variety of protective equipment, ranging in complexity and ingenuity from the rudimentary to the advanced.

Agricultural work came with many dangers. At the most basic level, workers, spending long hours under the hot sun, protected themselves with headgear. The bucolic poet Calpurnius Siculus describes them wearing close-fitting leather caps, while the archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie recovered a Panama-style straw hat during his 1901-2 excavation season in Egypt, which may have served a similar purpose. It has since been radiocarbon-dated to AD 420-568, making it the oldest such hat in the world. According to the botanist Theophrastus, workers also attempted to avoid deadly bites and stings by wearing sturdy hand and foot coverings when venturing into dense undergrowth. This makes sense when read against Erycius’ poem about a man named Mindon, who, while cutting down a tree, was bitten on the foot by a spider; the bite became infected, turned gangrenous and his leg was amputated. It was common knowledge, too, that some plants had powerful properties, both positive and negative. Plutarch records that those tasked with harvesting the opium poppy were warned to be on their guard against the soporific fumes and to cover their noses and mouths with something, perhaps a mask made from leather or cloth, to prevent inhalation.

Aeneas Tacticus provided lengthy instructions on the practicalities of undermining during a siege: ‘One should fasten together the poles of two wagons … raised aloft, inclining toward the same point. Then, when this has been done, one should fasten on to the poles in addition other timbers and sorts of covering above and cover them over with clay. This device, then, could be advanced and withdrawn on its wheels wherever you desire, and those who are excavating could keep under this protection.’

Clearly, military miners were valued more highly than those who mined for minerals and metals: the latter had no such protection and laboured in miserable conditions, often – as skeletons recovered from ancient mines have shown – in shackles and chains. Pliny the Elder spent considerable time at the silver mines in Spain during his military service and described their workings in detail. Those responsible for processing the minerals, he recounted, tied masks made from animal bladders over their noses and mouths to prevent them from inhaling the dust and damaging their lungs. Their eyes were left unobstructed so they were able to see what they were doing. According to the scholar Julius Pollux, this makeshift mask was gradually developed and refined: a sackcloth filter was added and it began to be used in conjunction with bags and sacks worn elsewhere on the body, presumably to protect sensitive areas of skin from injury and infection.

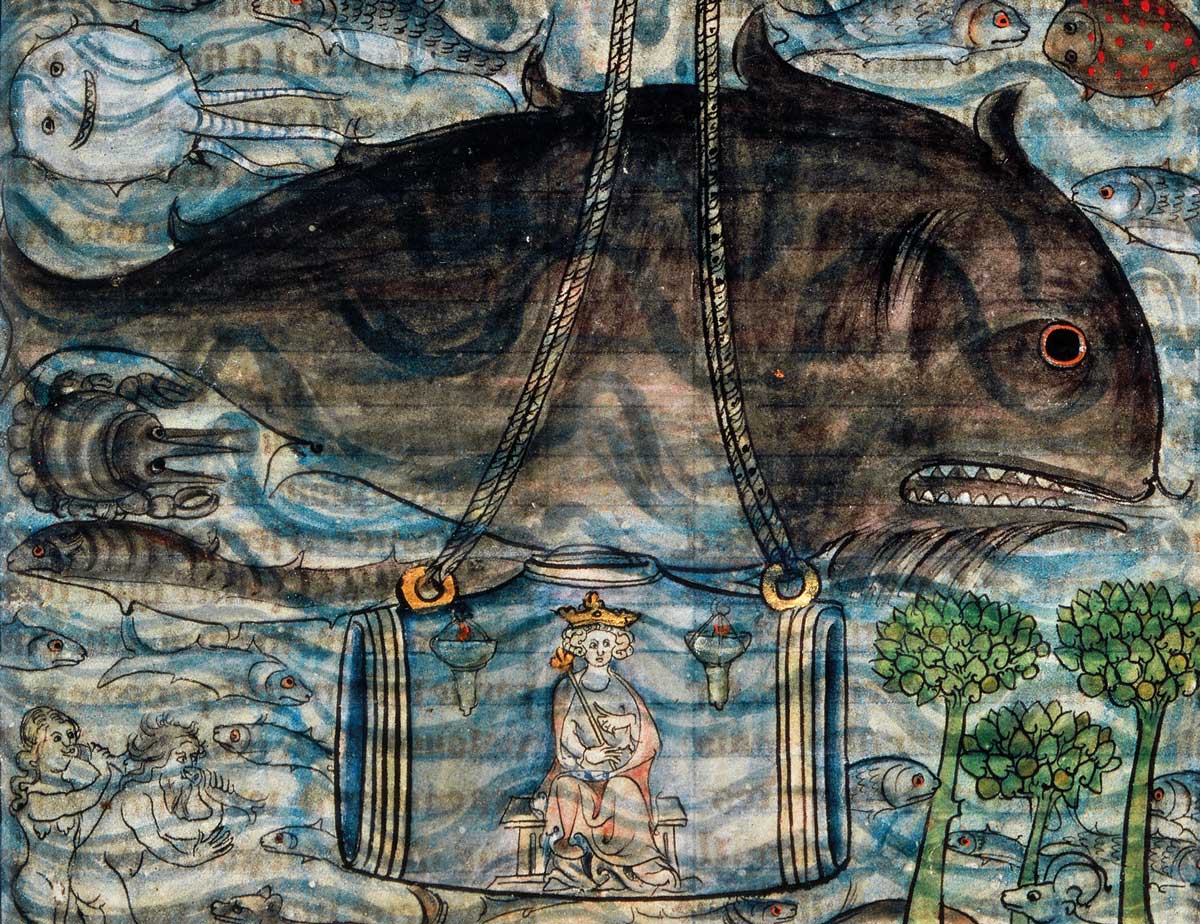

Divers on the lookout for snails used in the manufacture of purple dye, sponges, pearls, or even salvage from shipwrecks, would routinely bind sponges around their heads. Aristotle concluded that it was to protect their ears. Lycophron suggested in his only surviving poem that, on occasion, divers would also wear rudimentary leather wetsuits to inure themselves to the freezing water. While much ancient diving seems to have taken the form of what we know today as freediving, Aristotle’s repeated writings on the subject make it clear that breathing apparatus akin to a snorkel was sometimes used – and it seems some divers went even further than that, making rudimentary diving bells out of cauldrons that could retain a certain amount of air even while submerged. Over the centuries, stories about these tactics spread and became increasingly imaginative, elaborate – and, ultimately, fictional. They eventually found themselves incorporated into the medieval phenomenon of the Alexander Romance, in which Alexander the Great was portrayed commanding an ancient precursor to the modern submarine. This contraption was thought to have consisted of a bubble, barrel or case made of glass that was placed on a ship, taken out to sea, then lowered over the side and all the way down to the seabed on a metal chain, allowing Alexander, in relative safety and comfort, to conquer the sea as he had conquered the land.

Just as warriors, whether soldiers or gladiators, wore armour to protect themselves from injury and death during battle, other, less high profile, types of ancient workers also used personal protective equipment as a matter of course in their daily lives. But it is important to note that, since much of this work was undertaken by the enslaved and formerly enslaved, considered to be the lowest of the low in ancient Greek and Roman society, the physical and mental welfare of the members of the workforce was not uppermost in the minds of those in charge of and responsible for them; they were not considered to be individuals of consequence, or even individuals at all. In fact, ancient authors routinely referred to them as ‘articulate tools’. Rather, it was their productivity that was privileged. Consequently, these measures were not only aimed at protecting the frail human body, they were also aimed at augmenting it to provide a functional advantage in an inhospitable environment, somewhere that humans would not, or could not, normally go, all in the pursuit of financial gain for a relative few.

Jane Draycott is Lecturer in Classics at the University of Glasgow.

Source: History Today Feed