Caravaggio Lost at Sea | History Today - 11 minutes read

In early July 1610 Caravaggio set sail from Naples, carrying several mysterious paintings. Some four years earlier he had been sentenced to death for killing a Roman nobleman in a duel and had been living the life of a fugitive ever since. A brilliant artist, he had had no difficulty finding patrons; but his restless character – coupled with a volcanic temper – had prevented him from staying anywhere for long. After a brief stay in Naples he had gone to Malta, where he had become a Knight of St John and painted some of his most extraordinary works. Following a violent brawl Caravaggio had been arrested and thrown into prison. He made a daring escape and fled, first to Sicily, then back to Naples. But his troubles were getting hard to shake off. In October 1609 he was attacked, most likely by bravi sent from Malta. He had to get out of there but there was nowhere left to run. Seriously ill, he saw Rome as his only hope and looked to his patron, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, for help. The two struck a deal. Borghese would obtain a pardon; in return, Caravaggio would give the cardinal all his unsold works. Nothing was guaranteed, but in the expectation that Pope Paul V would soon lift the bando capitale, the ailing Caravaggio was now leaving for Rome with several paintings, carefully packed in wooden boxes.

A week or so after leaving Naples, Caravaggio’s felucca put in at Palo Laziale, a Spanish-held port defended by a large garrison. No sooner had he gone ashore than things went badly wrong. No one knows exactly what happened. Maybe there was some misunderstanding over paperwork; perhaps Caravaggio simply picked a quarrel, as he was wont to do. Whatever the case, he was immediately placed under arrest. Seeing trouble brewing, the felucca hastily put out to sea again and set off for Porto Ercole, around 50 miles further north, taking Caravaggio’s paintings with it.

After a few days, Caravaggio managed to buy his freedom. He immediately went in search of his paintings – the key, as he saw it, to his pardon. According to his biographer, Giovanni Baglione, ‘he started out along the beach in the cruel July sun, trying to catch sight of the vessel which was carrying his belongings’. More likely, he simply rode by post along the coastal road. Either way, he made it to Porto Ercole by 18 July, arriving at the same time as, or even slightly before, the felucca. But prison and the journey had taxed him more than his failing health could bear. On 19 July, he died.

The scramble for Caravaggio

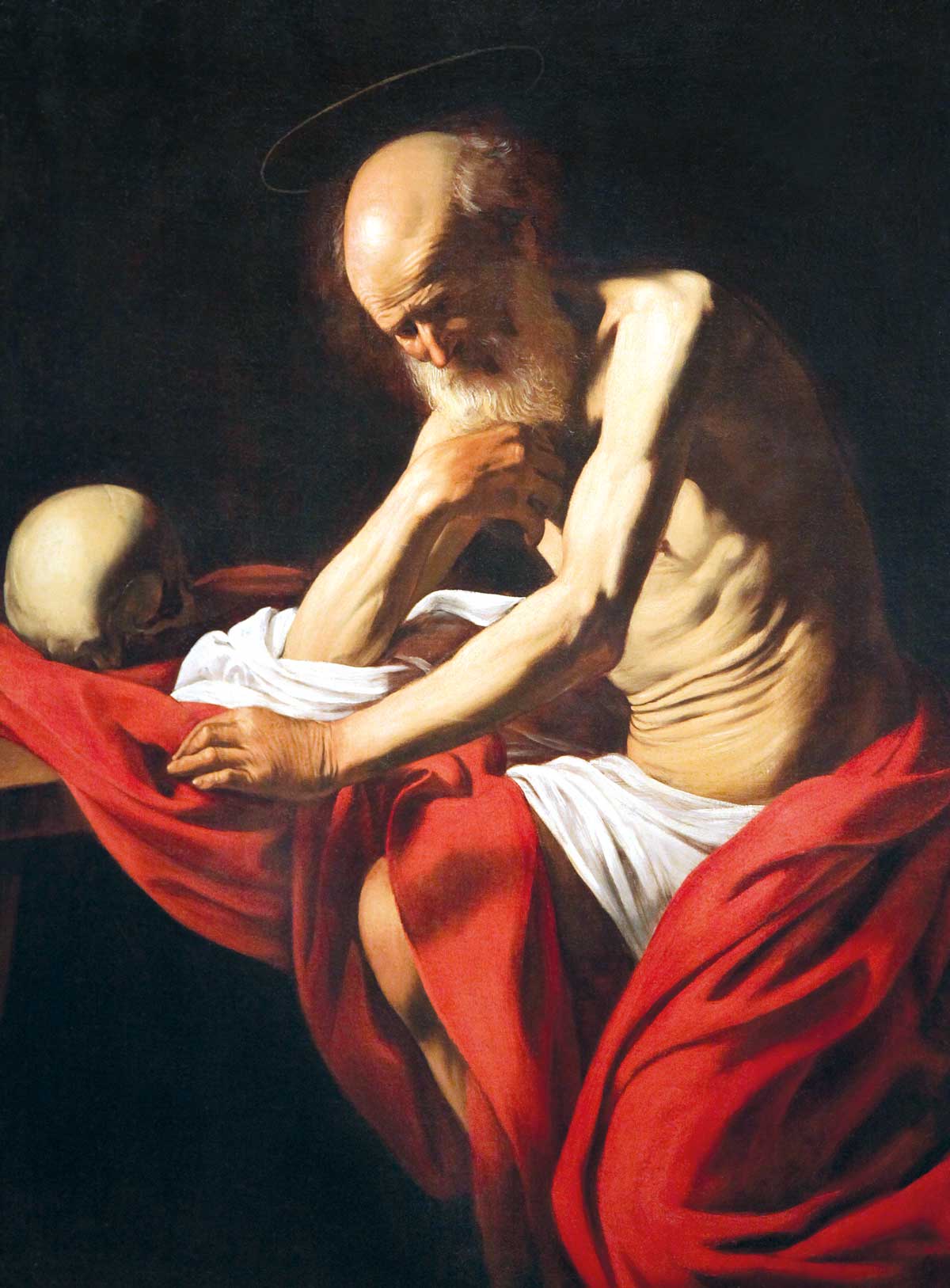

There was no funeral to speak of. Caravaggio was buried without ceremony in a pauper’s grave. Perhaps a few of the crew came along, for form’s sake. But the captain, who had no cause to linger, soon returned to Naples. News of Caravaggio’s death quickly began to spread. Among connoisseurs, the shock was profound. Wherever his work was known, there were outpourings of grief. But there was even more interest in his final paintings. Scarcely had the felucca arrived in Naples than an undignified tussle began. Scipione Borghese was first out of the blocks. He maintained that, since Caravaggio had promised them to him, they were his by right and sent his agent, Donato Gentile, to find them. On 29 July Gentile finally tracked three of them (‘two Saint Johns and [a] Magdalene’) down to the palace of Caravaggio’s former patron, Costanza Colonna Sforza. But before he could do anything, the Order of Malta’s Prior of Capua suddenly appeared on the scene. Bursting into the palace, the prior took the paintings by force. Conveniently forgetting that Caravaggio had been defrocked, he asserted that, whenever a knight died, his estate reverted to the Order – and that the cardinal could get stuffed. On Gentile’s advice, Borghese asked the Spanish viceroy, Pedro Fernández de Castro, to intervene. But it was not until August that Castro did anything – and even then, he merely ordered the commander in Porto Ercole to send him whatever of Caravaggio’s belongings remained in Tuscany. By the time they were next heard of the following January only one of the paintings could still be located – a Saint John the Baptist. What had become of the others, no one seemed to know.

Love at first sight

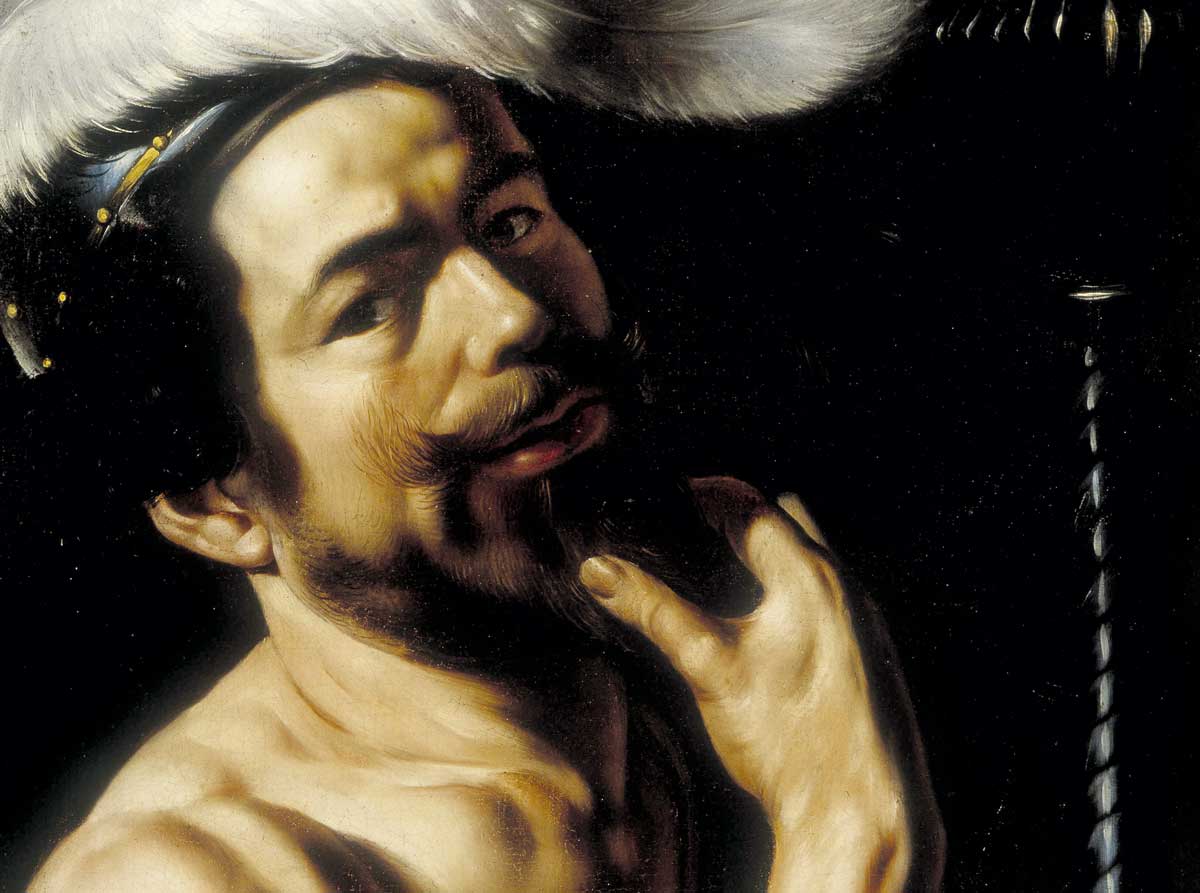

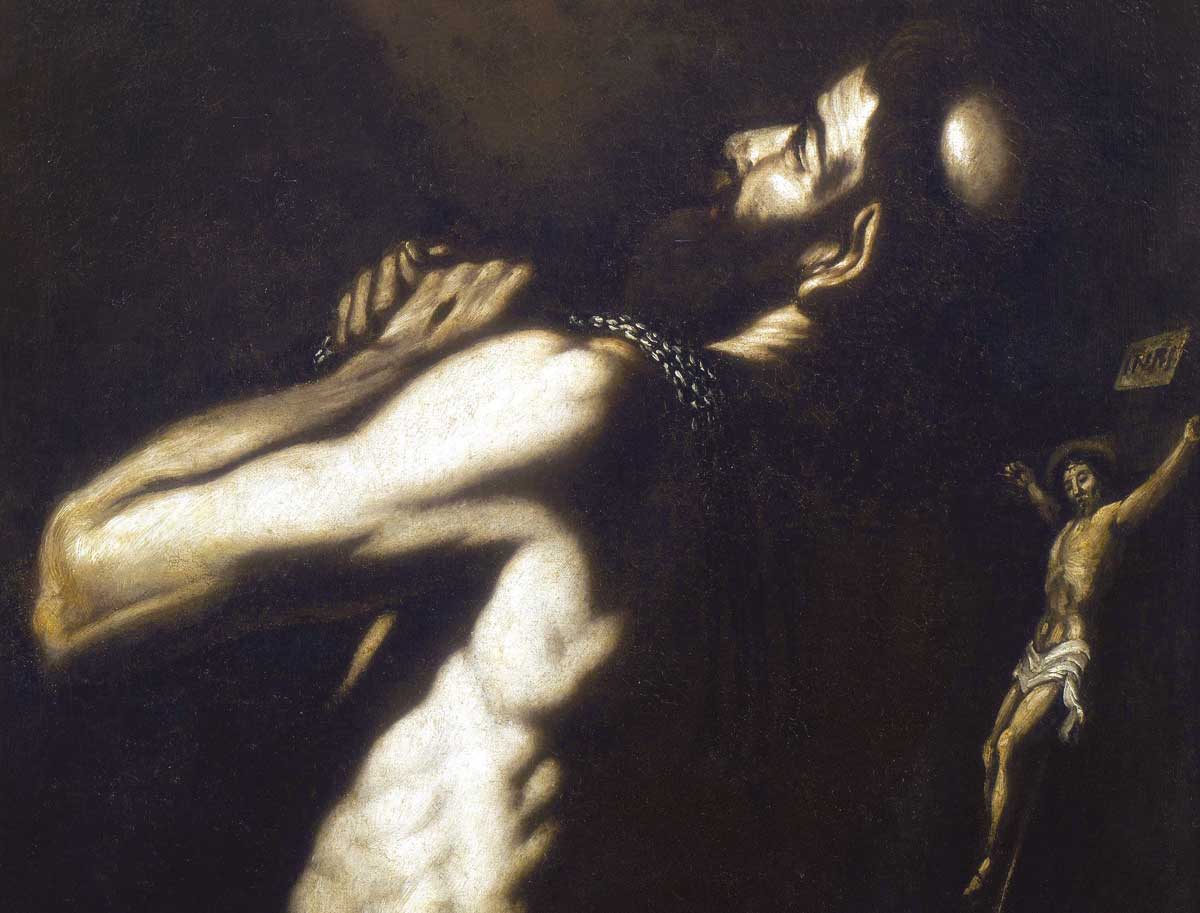

For almost 400 years nothing more was seen of them. Then, in 1978, a young medical student named Christian Morand had a stroke of luck. He was at an exhibition of Provençal art in Marseille when he stumbled across two paintings which took his breath away. Attributed to Louis Finson, a Flemish painter who knew Caravaggio in Naples and often copied his style, they had come from the collection of the polymath Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and were unlike anything else on show that day. One was of Saint Sebastian, the other of a penitent, whom the catalogue identified as Saint Jerome. Large, tenebrous and brooding, they conveyed both an intense suffering and a profound desire for forgiveness. All at once, Morand ‘fell in love’.

Some 13 years later, in 1991, Morand learned that the two paintings were going to be put up for auction. By then an ophthalmologist with a practice of his own, he urged Marseille’s Musée des Beaux-Arts to buy them, only to be told that there was no money. Undeterred, Morand went to the sale himself, determined to save the paintings for Provence. He started bidding but was soon out of his depth and watched glumly as they were snapped up by someone looking like an ‘Italian mafioso’.

He thought no more about the paintings until a few months later. While in Avignon with his family, his infant son began to cry. Realising that they had left the child’s bottle in a café, Morand hurried back to get it. He took a shortcut down an unfamiliar street and stopped dead. There in a shop window were the two paintings. Bewildered, he went straight in and told the owner his tale. Morand still didn’t have enough money to buy them, but the owner was so taken by his passion that he offered him a deal. Morand could take the paintings away with him. Each month, he would pay what he could. In return, he would allow the owner to come to see them whenever he liked.

Morand was delighted. He bought a splendid new home and the two Finsons became the core of a burgeoning art collection. But, as the years passed, he and his family began to wonder if they really were by Louis Finson. It is easy to see why. They are extraordinary paintings. Though Finson was a noted imitator of Caravaggio’s style, they seem almost too good to be mere imitations. They are quite unlike his other works of the same period. And, tellingly, they are also unsigned. It begged an obvious question. What if they were by Caravaggio instead? It was a tempting thought. But, for the moment, it was just a hunch. Besides, if it were true, Morand realised, it would cause all kinds of difficulties. He’d have to pay for special insurance, arrange for proper security, deal with conservation … and there was no way a young ophthalmologist could afford all that. So, for the time being, he left the possibility at that.

Caravaggesque

Then, in 2014, something happened to change his mind. A painting of Judith Beheading Holofernes was discovered in an attic in Toulouse. Similar in style to Morand’s paintings, it, too, was unsigned; and there had been much debate about the attribution. Some experts thought it was by Finson – or perhaps another Caravaggesque painter working in southern Italy. But others were convinced that it was a lost painting of Caravaggio’s, which he had given to Finson and Abraham Vinck when he left Naples for the first time in 1607. This generated so much excitement that the American billionaire, Tomlinson Hill, snapped it up before it could even be brought to auction.

The possibilities this opened were almost too tantalising to resist. Together with his two sons, Morand now began digging deeper. They consulted specialists, visited dozens of galleries and archives and sent their ‘Finsons’ for a barrage of tests. Unable to find any other artists who could have painted the two works, they became convinced that Caravaggio was the only plausible attribution – and that they had found two of the paintings the artist had lost at sea in 1610. Slowly but surely, they built up a theoretical narrative to explain how they ended up in Provence. After Caravaggio’s death, a Roman antiquarian called Lelio Pasqualini acquired several of his works, including a Saint Sebastian and a penitent. This soon came to the attention of Scipione Borghese, who took steps to have them seized. Just in time, the ailing Pasqualini spirited away his most treasured possessions. Via Louis Finson (who doubled as an art dealer) the two Caravaggios then passed separately to Pasqualini’s friend, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. At his death, Peiresc had them mounted on either side of his tomb; but since his heirs had little interest in preserving any record of the artist’s ‘true’ identity, Caravaggio’s authorship was gradually forgotten.

The journey to Rome

There is no denying that it’s a great story. And there is a lot to recommend it. After leaving Naples, Finson went first to Rome, then to Marseille. During his time in Provence, he is known to have had nine Caravaggios in his possession and it was also there that he met Peiresc. There is no doubt that Peiresc bought one of these paintings from Finson in 1613 and, before acquiring the second, warned against allowing the Saint Sebastian to leave Provence, lest it ‘add to his martyrdom’. Perhaps most intriguing of all, x-rays of the penitent revealed a turned-up nose, just like Caravaggio’s own – a sign, perhaps, that it may have been intended as a self-portrait.

There are also questions that remain unanswered. Since the subject of at least some of Caravaggio’s ‘missing’ paintings is unclear, the only way of being sure that Morand has found them is by tracing their path directly from the felucca to Provence. But there seems to be a gap. Although the Morand family has offered a reasonable account of how they got from Pasqualini to Peiresc, the route they took to Pasqualini is hazy at best. We can be certain that, after Caravaggio’s death, the Prior of Capua took a number of paintings from the Colonna palace in Naples in the name of the Order. He is most likely to have sent them back to Malta or used them to settle Caravaggio’s debts. It is possible that Morand’s paintings were among those he took and had simply been overlooked or misidentified. Alternatively, the Prior never laid hands on them. Either they had been smuggled out of the Colonna palace a few days before or they had been left behind in Porto Ercole. Whatever the case, the question remains the same: how did they get to Pasqualini? Given that he had resigned his offices on grounds of ill health in 1610 and died the following August, Pasqualini is unlikely to have undertaken any great journeys. So who brought them to him in Rome and why?

Afterlife

In a sense, this hardly matters. The fact that Caravaggio’s ‘final’ paintings were lost – and that the Morand family believe they have found them – is testament to his afterlife. Since his youth, he had been a troublemaker. He spurned convention, held law in contempt and never shied from a fight. His habits were singular. Unlike his contemporaries, he worked alone, in a style entirely his own – and rarely showed his patrons the slightest respect. Yet his paintings captivated people. Though later reviled by Baroque classicists, his dark and turbid canvases possessed an intensity that few could deny and none could ignore. He has inspired generations of imitators and his influence on the visual imagination remains pervasive. Anachronistically, he has come to embody the modern notion of the tortured genius, a life filled with passion and sorrow, triumph and disaster. From the vantage point of an anodyne age, it is all too easy to find in him in a romance. We want to seek out the missing pieces, to find those shards of a shattered life; for, even if we are wrong, we see the world through his eyes and share, however briefly, in the excitement of his world. And that is surely no bad thing.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, is now available in paperback.

Source: History Today Feed