The Battle of the Gauges - 10 minutes read

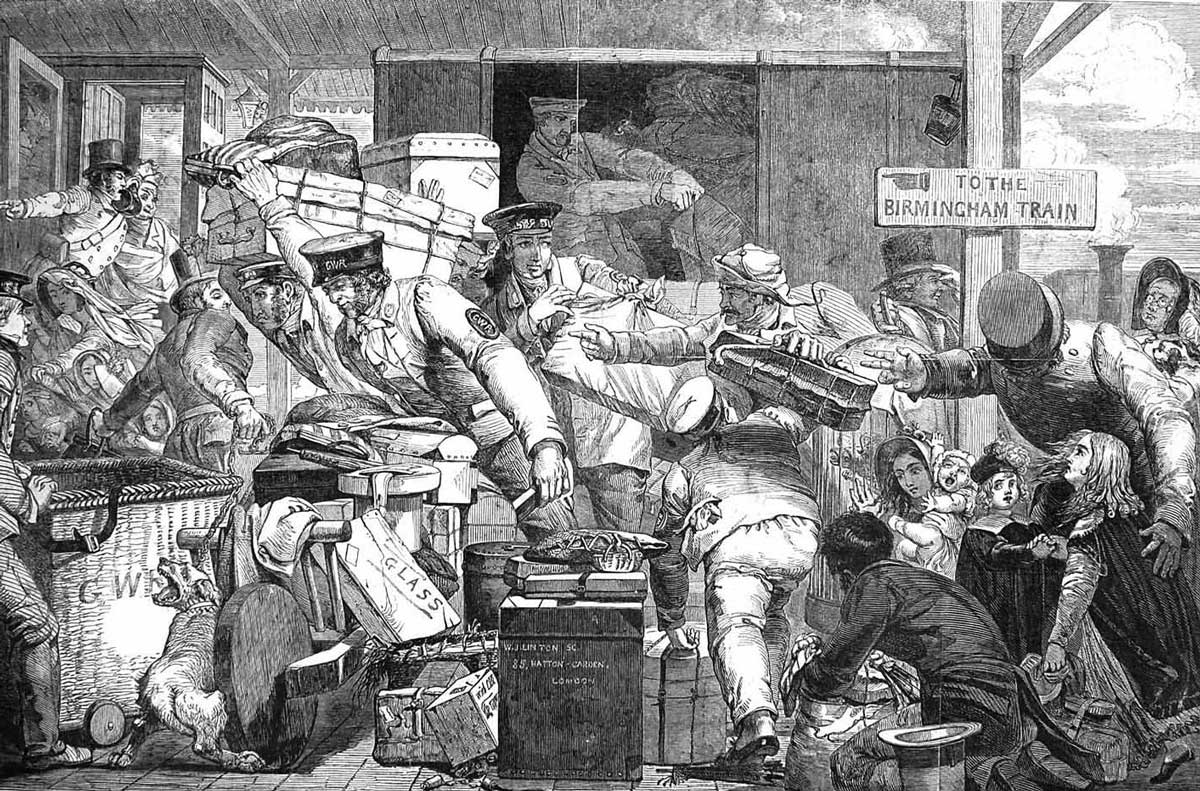

Queen Victoria was definitely not amused. Whenever she travelled from her estate on the Isle of Wight to her castle at Balmoral, she encountered the inconvenience of twice changing trains, once at Basingstoke and again at Gloucester. She had no choice: even royalty was obliged to mind the gap between railway tracks of different widths. Stations were regularly plunged into chaos as angry passengers and their cumbersome luggage were transferred between two sizes of train, while disgruntled manufacturers repeatedly protested about the delays and expense caused by the transition from one gauge to another. The Railway Clearing House estimated that each track shift added the equivalent of 20 miles to transport costs, but the business titans in charge refused to yield. By 1866, despite numerous attempts to impose conformity, there were still around 30 stations in Britain where the rails abruptly altered width.

This clash of wills and technologies – soon dubbed the Battle of the Gauges – lasted for decades. The major conflict was between supporters of narrow gauge and broad gauge tracks, which might sound as farcical as the episode in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, when the Lilliputians argue about whether boiled eggs should be opened at the big end or the little one. But the outcome – eventual victory for the narrow gaugers – entailed long-term, international consequences. Rather than being a petty squabble between petulant technophiles, the Battle of the Gauges resulted in two Acts of Parliament within two years and divided public opinion about the relative merits of modernisation and tradition.

Right on time

Regarded apprehensively by many, the powerful ‘iron monster’ revolutionised Victorian Britain. In 1830 fewer than 100 miles of track existed; by 1852 there were 6,600. Distances seemed to shrink, as smelly steam trains outstripped the fastest horses and straight steel lines reached out across the land to replace winding muddy roads. Overhead messages flashed almost instantaneously along telegraph wires that – as Charles Dickens put it in Hard Times – ruled ‘a colossal strip of music paper out of the evening sky’. Some visionaries enthused about placing ‘a girdle around the globe’ that would unite the world under the banner of British Christianity, while others envisaged a system of tracks elevated above the streets of London.

People even began to think differently. Punch predicted that ‘Distance, of course, will no longer figure in the maps, but time will be the substitute. “How many miles?” will be altered into “How many minutes?”’ Yet although distance was apparently contracting, travellers regularly ventured further afield than previously and so spent many long hours confined in a carriage.

The nation became united not only physically but metaphorically: to prevent timetabling chaos, clocks at every station were forced to synchronise with Greenwich Observatory instead of telling their own local time by the midday sun. In the absence of telephones and radios, trying to coordinate thousands of individual timepieces scattered across the country proved tricky and this new problem generated diverse solutions. The harbour tower at Ramsgate carries this inscription: ‘The first Stroke of this Clock at the hour of Twelve indicates Greenwich Mean Time / Ramsgate Mean Time is 5Mins 41Secs faster than this Clock’. As late as 1940 Ruth Belville – last inheritor of a family ritual stretching back for a hundred years – was still tramping round the streets of London with her special watch conveying Greenwich time.

Benjamin Franklin fretted that time was money, but before the 19th century, precise punctuality was neither a national obsession nor a moral requirement. Like Josiah Wedgwood, some factory owners clocked their workers in and out, but more widely, times were approximate, governed by the sun and the local church tower rather than by personal watches. The advent of trains contributed to demolishing this leisurely approach of running life in harmony with natural rhythms. Members of the landed gentry, who had once been accustomed to ordering a horse from the stables at their own convenience, now discovered that they had lost charge of their daily schedule and had to abide by timetabling prescriptions. New expressions emerged, such as having all the time in the world to complete a task. Before then, time had never seemed to be in short supply. The need to turn up promptly at the station led to anxieties that have become only too familiar. One satirical poster about ‘The Wonders of Modern Travel’ included ‘Wonder if my watch is right, or slow, or fast. Wonder if that church clock is right … Wonder if I’ve got time to get a sandwich and a glass of sherry’.

Yet although railway entrepreneurs forced their passengers to obey Greenwich time, they manifested very little coordination among themselves. In 1844, when J.M.W. Turner painted Rain, Steam and Speed – the Great Western Railway, there were around 100 separate companies, each headed by competitive men who were determined that their own interests should prevail. The financial stakes were high in this national carve-up: the value of shares in the London and North Western Railway Company exceeded the capital of the East India Company.

Battle lines

On one side of the Battle of the Gauges lay the more cautious developers, the ‘narrow-track’ brigade, who followed the lead of the steam pioneer George Stephenson – but they were being challenged by a daunting rival, the visionary engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who envisaged a technological future dominated by wide tracks and high speeds. Since Turner owned shares in Brunel’s venture, it is presumably no coincidence that his painting’s title specified ‘the Great Western Railway’, which had recently been extended and would finally stretch from Paddington to Penzance; for a while passengers could alight at Bristol to board a Brunel steam ship across the Atlantic.

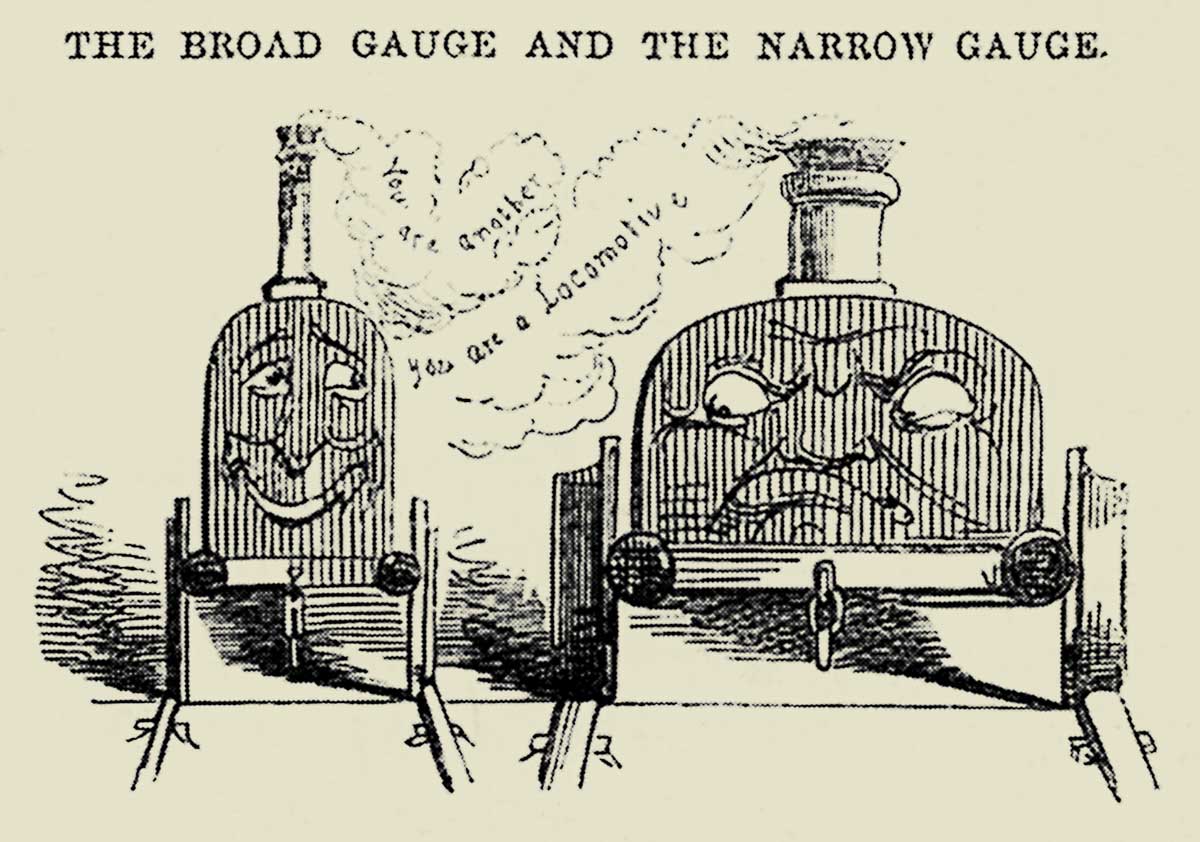

Many contestants in the Battle of the Gauges developed subversive tactics. One goods manager at Gloucester eventually confessed that he had contrived an exceptionally shocking state of confusion to impress visiting inspectors, a debacle that was exaggerated still further by satirists who lampooned flustered passengers and incompetent staff. A century before Thomas the Tank Engine was born, cartoonists depicted rival fat and thin engines engaged in imaginary conversations, while The Comic Bradshaw (named after the famous series of railway guides and timetables) pithily summarised the nub of contention: for shareholders in Brunel’s Great Western, the ‘narrow gauge is a paltry humbug’, but for rival investors, ‘the broad gauge is an extravagant quackery’.

Stephenson’s narrow tracks had been introduced first. Originally designed to carry engines transporting coal for the northern mining industry, they were tailored to match the width needed for accommodating a horse between wagon shafts. Initially there were small local variations, but this animal-based dimension was perpetuated into the future when Stephenson decreed that it made sense for all his new trains to adopt the same gauge, 4 feet 8½ inches (1.435 metres). When the railway network began expanding, he recommended that this width should be adopted around the country, a deceptively arbitrary measurement still used by over half the world’s railways.

Once the British network began expanding, Brunel came up with characteristically bold plans for improvement. Convinced that the country would eventually be divided into distinct zones operated privately and separately, he embarked on building faster, larger engines that ran smoothly along tracks of a far wider gauge – 7 feet ¼ inch (2.14 metres). The success of this innovation depended on Brunel’s unprecedented engineering triumphs in constructing long bridges and deep tunnels. Although his trains were more expensive to build, passengers appreciated the reduction in journey times and the luxurious comfort. The Great Western could top 60 miles per hour, while a rival express service from London to Liverpool managed only 36 to 38.

Although apparently a technical tussle, the Battle of the Gauges divided the nation because it carried long-term implications. Turner’s wonderfully ambiguous Rain, Steam and Speed evoked some of its tensions and the conflicting emotions experienced by early Victorians. Despite being relatively small, his arresting image aroused panic in viewers unused to travelling faster than the pace of a horse. A dark engine with a glowing face hurtles out of the canvas towards the viewer, belching puffs of steam as it emerges through a storm. By blurring and spattering the paint, Turner has intensified the confusion, the sense of dizzying disorientation at high speeds. Critics were stunned but divided: the novelist William Thackeray remarked that the rain was composed from ‘dabs of dirty putty slapped on to the canvas with a trowel … The world has never seen anything like this picture’.

This engine of modernity seems to be trampling everything in its path except for the emblem of speed, the hare racing along the tracks. This tiny creature could still outpace its mechanical rival – but for how long? Turner probably knew that one of Brunel’s new ‘Firefly’ locomotives was called Orion, the hunter eternally transfigured in the stars to chase the nearby constellation of Lepus, the hare. The train is crossing Maidenhead Bridge, recently constructed by Brunel with a controversial design of two semi-elliptical arches that critics predicted – wrongly – would soon collapse. Turner has contrasted this headlong rush towards the future with the stability of England’s rural past. To the right, a traditional ploughing team sedately continues its work, while the other side is dominated by the sturdy pillars of the old road bridge across the Thames.

A narrow victory

A Royal Commission was set up in 1845, but, as so often happens, the committee members – who included the Astronomer Royal – collected a great deal of evidence yet failed to resolve the conflict. While many passengers preferred Brunel’s fast comfortable trains, their opponents warned that such high speeds were dangerous. The final report agreed that Brunel’s wider trains were quicker, but it also stressed two powerful financial arguments: if existing tracks were to be converted, then broad to narrow was considerably cheaper; and four times as many miles of narrow track had already been laid. Although the Commission came down on the side of the narrow gauge contingent, the government prevaricated by opting for compromise and enacting some unsatisfactory legislation. The 1846 Act decreed that future tracks should all be narrow gauge, but it permitted the broad track ones to remain and – crucially for Brunel – to be extended. Brunel kept building and kept fighting, although by the end of the century he had admitted defeat. Uniformity prevailed, just as Stephenson had first proposed.

The Battle of the Gauges might have been won, but the war was far from over. This was no mere wrangle over a few inches, but a national debate about scientific innovation. Which should have priority: technological progress, private profit or public safety? Although environmental damage had not yet become a matter of major concern, critics complained that the noisy, dirty engines were destroying rural peace and threatening traditional ways of life. The most obvious modern parallel is the development of HS2, but controversies about many other projects demonstrate that these fundamental questions about the role of technology, the goals of humanity and the nature of progress have still not been resolved.

Patricia Fara is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. Her latest book is Life after Gravity: The London Career of Isaac Newton (Oxford University Press, 2021). ‘Great Debates’ will run every other month, alternating with Alexander Lee’s new column, which will begin in the April issue.

Source: History Today Feed