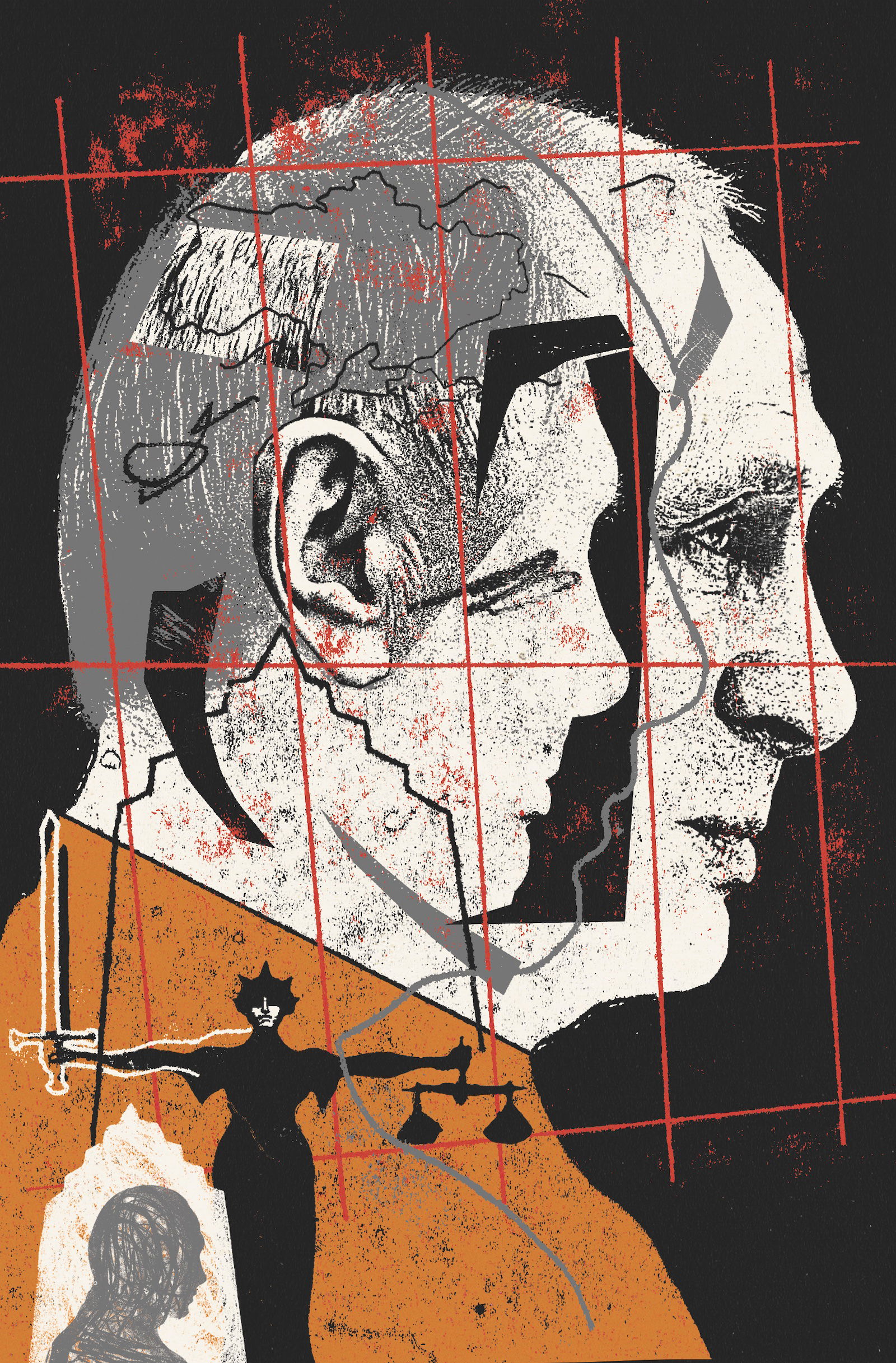

Will Putin Get His ‘Nuremberg Moment’? - 8 minutes read

Interviewed in the Guardian in March 2022, the international lawyer Philippe Sands said that: ‘The world changed in 1945. It was a revolutionary moment. For the first time, states agreed that they were not absolutely sovereign, that they could not kill individuals or destroy groups.’ Sands called this the ‘Nuremberg moment’. In the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, ‘Nuremberg’ has compelling significance. Vladimir Putin described the invasion as a ‘special military operation’; international lawyers characterise it as a ‘crime of aggression’ – a legal term inherited from Nuremberg. Sands and others, notably former British prime minister Gordon Brown, demanded, as the Daily Mail informed its readers: ‘a new Nuremberg trial to make Putin pay … Let him face the legacy of Nuremberg.’

Crimes without a name

Between June and August 1945, before the trials of Nazi war criminals began, international lawyers had gathered in London to debate the legality of the prosecutions. They confronted a question: what crimes, under existing international law, had the Nazi leaders committed? Would it be necessary to devise new laws? Winston Churchill had (perhaps) anticipated this when he described reports of the mass killings of Jews on the Eastern Front as a ‘crime without a name’. Some of the complex issues debated at the London Conference in 1945 have never been resolved. Nevertheless, the ‘London Agreement and Charter’ became the legal foundation of the trials that would take place in Nuremberg.

At the same time that Sands and others proposed a new tribunal to bring Putin and his warmakers to account, the International Criminal Court (ICC) set in motion proceedings to prosecute Putin, his advisers and other alleged perpetrators. By issuing arrest warrants for Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian Commissioner for Children’s Rights, the ICC was playing a high-stakes game of name and shame. Neither Russia nor the US ratified the ‘Rome Statute’ that created the ICC and so neither state is subject to its requirements. The chances that Putin, or any member of his regime, will be arrested and tried are slim. Russia retaliated by opening a case against the ICC judges and prosecutors on the grounds that the ICC had acted illegally under Russian law. The Duma is considering legislation that would punish anyone co-operating with the ICC. The war in Ukraine has opened a legal battlefield – a terrain which is littered with complex and highly specialised legal principles that offer a plenitude of opportunities for dissent – and resolution.

Laws without punishment

After 1945, international courts took on unprecedented roles in the unfolding of real-world history. International criminal law began to influence historical actors. Even heads of state could be held responsible and prosecuted. The dictum of ‘Never Again’ may often be a chimera, but it reflects the legal revolution that defined and proscribed, for the first time in history, a legal term unknown before 1945: genocide. The deceptively simple definition – ‘Acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethical, racial or religious group’ – is packed with legal notions such as ‘intent’ that have proved notoriously difficult to resolve.

International criminal law has regulated relations and conflicts between states for centuries. ‘Jus ad bellum’, the moral justification for resorting to armed force, is rooted in Roman law and preoccupied medieval thinkers; in the 17th century, the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius, in his legal masterpiece De Jure Belli ac Pacis (On the Law of War and Peace, 1625), recognised that since certain uses of force by rulers and states might be unjust, aggression could be judged as such and thus criminalised, and perpetrators prosecuted.

Yet Grotius and those who followed had no means of seeing beyond the near-sacred doctrine of state sovereignty that was consecrated by the 1648 ‘Peace of Westphalia’. The idea that a ‘third party’ such as an international court could take precedence over states was anathema. The ‘Hague Conventions’ of 1899 and 1907 established rules of conduct by treaty and thus created international law, but do not provide any legal tool to realise their ideals. In practice, the laws of war provided guides to conduct rather than enforceable laws. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the Hague Conventions were habitually flouted by combatants – and not only by fascist powers. One of the Nuremberg judges lamented that ‘The Hague Convention [sic] nowhere designates [certain] practices as criminal, nor is any sentence prescribed, nor any mention made of a court to try and punish offenders.’

This explains why the ‘Nuremberg moment’ was truly revolutionary. On 8 August 1945, after much wrangling behind closed doors, the delegates drew up four counts of crimes for which the Axis leadership could be legally prosecuted: ‘crimes against peace’; ‘crimes against humanity’; war crimes (meaning violations of the existing laws of war); and a ‘common plan or conspiracy to commit’ these acts. Only ‘crimes against humanity’ was truly innovative, encompassing murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and other inhumane acts. International law could now hold the Nazi leaders criminally liable for offences against their own citizens in peacetime, regardless of whether domestic law permitted their actions.

After Nuremberg

The Cold War blunted the impact of the ‘Nuremberg moment’ until the collapse of the Soviet Union and the savage Balkan wars of the 1990s. The establishment of the ICC through the Rome Statute (1998) inaugurated a succession of international criminal tribunals that were appointed to investigate war crimes and genocide in the territories of the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and Cambodia. Nuremberg meant that a ‘third party’, in the shape of an international court, could challenge the borders of sovereign states and that international criminal lawyers finally had the means to prosecute and punish individual state actors. What this means for historians is that the ‘Nuremberg moment’ decisively transformed the way history is made.

As a consequence, history-makers such as army commanders, soldiers, political leaders, bureaucrats, officials and even, in the case of the Rwandan genocide, radio producers and other propagandists, can become subjects of international criminal law. This means that historians must become familiar with some tricky legal concepts.

Take, for example, the ‘Genocide Convention’ (1948), an international treaty that obliges state parties to both punish and prevent a crime defined as the intent to destroy any of four enumerated groups: national, racial, ethnic or religious. This legal definition of genocide is hedged with challenges such as the definition of a ‘group’ and the meaning of destruction ‘in whole or in part’. Just as problematic is the duty to prevent. How might this be achieved? The answer to that question requires us to grasp a fundamental concept in Anglo-American common law. According to Article 3 of the Convention, the punishable acts are (a) Genocide; (b) Conspiracy to commit genocide; (c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide; (d) Attempt to commit genocide; and (e) Complicity in genocide. All of these are defined as ‘inchoate crimes’. This means they do not have to be completed to be punishable acts. As in common law where, for example, engaging in a conspiracy to commit a robbery or murder is a criminal act, the planned act need not be carried out. Under the Convention, then, conspiring, inciting or attempting genocide are legally punishable crimes.

Precedent or innovation?

Accusations of genocide are powerfully stigmatising. As we know from allegations of genocide against the Uighur people in China and the Rohingya in Myanmar, states react aggressively. And the Genocide Convention provides international lawyers who act for these accused states with knotty legal challenges. Notably, prosecutors must prove that the accused state – or, in a number of cases, non-state parties such as the Republika Srpska that enacted the Srebrenica genocide – had the ‘dolus specialis’ or ‘special intent’ to carry out the destruction of a group. It is not enough to commit the most egregious atrocities if these actions are not proven to be committed with genocidal intent.

One implication of the ‘Nuremberg moment’ is, I suggest, that familiarity with international law should be added to the toolkits of historians. If law shapes human action, it shapes history. One of the problems debated during the London Conference was the legal concept of ‘Nullum crimen sine lege’, no crime without a law: the principle that no one should suffer prosecution and punishment for an act that was not criminalised. The problem of retroactive law-making bedevilled discussions at the London Conference – and has never been completely resolved. The legal experts at the Conference had to justify innovative law-making to capture the scope of Nazi atrocities – crimes, as Churchill had said, without names.

Law pivots between conservative precedent and innovation – and both history-makers and historians would be advised to keep up to date. Returning to where we began on the battlefields of Ukraine, the raft of ongoing investigations, indictments and legal initiatives – in short, the pursuit of accountability for Russia’s crimes against peace – suggests that the conflict may end not at a negotiating table but in a courtroom.

Christopher Hale is a non-fiction writer and producer. He recently received an LLM in human rights law from the University of Edinburgh.

Source: History Today Feed