Vile Verse and Desperate Doggerel - 6 minutes read

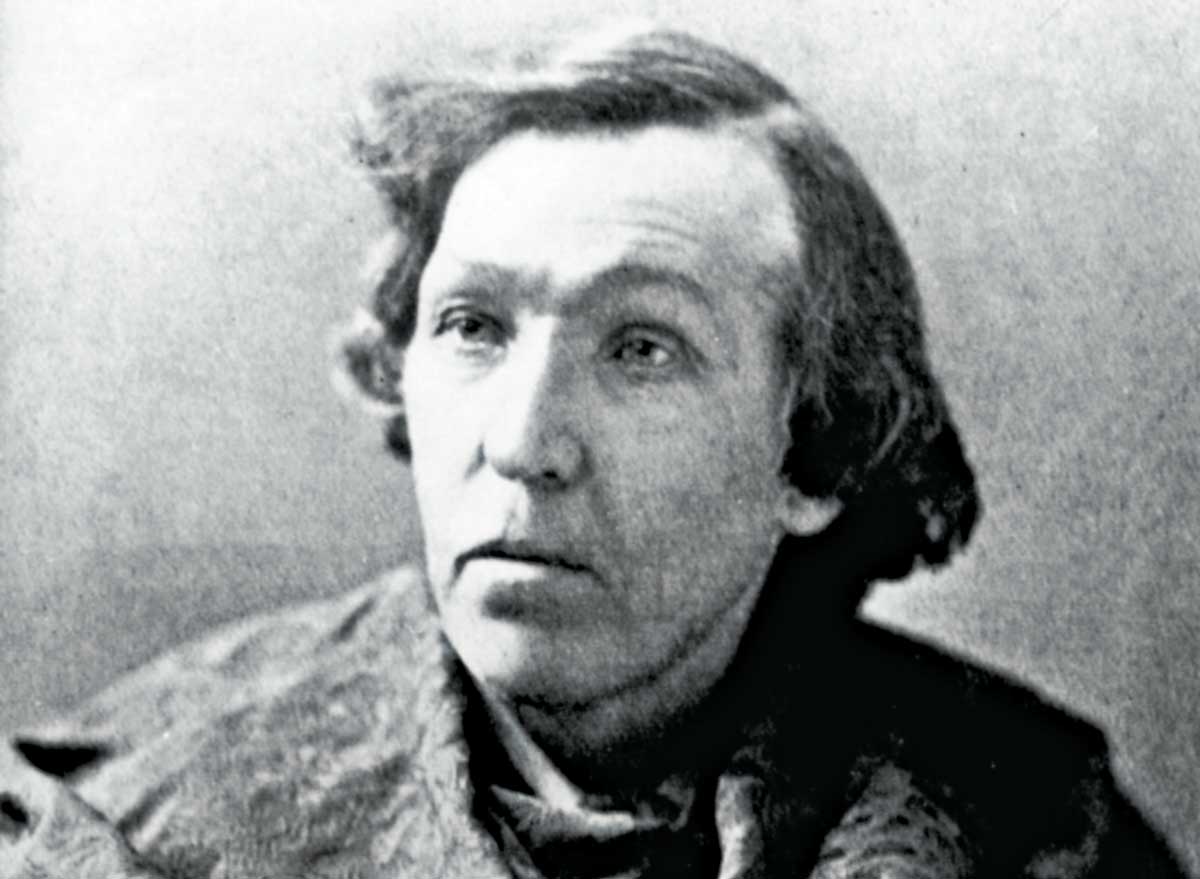

Despite his long-running status as ‘the worst poet in history’, William McGonagall has hardly lacked appreciation in literary culture since his death in 1902. Raised in Dundee by a working-class family with deep religious convictions, McGonagall followed in his father’s footsteps and became a weaver. His artistic inclinations were apparent at an early age; he committed the verses of his idol, Shakespeare, to memory and appeared in local theatre as the titular character in Macbeth. As he would later write in his inordinately self-dramatising autobiography, his fellow thespians were jealous of his acting, so he refused to die at the hands of Macduff in the final fight scene as penance for their bitterness.

When work became scarce in 1877, the 52-year-old McGonagall was struck by a ‘divine inspiration’ to write poetry. He recalled this moment with vivid theatricality: ‘It was so strong, I imagined that a pen was in my right hand, and a voice crying, “Write! Write!”’

His first work was a commemorative poem dedicated to his friend, the Reverend George Gilfillan, with the irregular, doggerel rhythm and clumsy rhyming that would come to define his repertoire:

Rev. George Gilfillan of Dundee,

There is none can you excel;

You have boldly rejected the Confession of Faith,

And defended your cause right well.

Verse that honoured the deceased was his forte; his most famous poem is a tribute to the victims of the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879, which claimed the lives of 75 people. The poem attempts to convey McGonagall’s sincere despair, but is a jumbled mess of misused words and metrical disarray:

The passengers’ hearts were light and felt no sorrow,

But Boreas blew a terrific gale,

Which made their hearts for to quail,

And many of the passengers with fear did say-

‘I hope God will send us safe across the Bridge of Tay.’

McGonagall’s works reflect his personal oddities. Appearing to lack self-awareness, he conducted himself with wholehearted honesty, never wishing to censor his nonconformist attributes. He enjoyed performing recitations in garish costume to unsuspecting crowds and appeared largely oblivious to their adverse reactions. In 1889, he wrote an epistolary verse of complaint to Dundee magistrates, who had banned his performances at the local circus due to the disturbances created by audiences who were encouraged to hurl food at him (‘Why should the magistrates try and punish me in such a cruel form? / I never heard the like since I was born’). The public disdain for his works could not have been more obvious, yet McGonagall seemed impervious to criticism, even if it came in the form of eggs and stale bread.

His career would never reach the heights he so dearly desired. Even a 60-mile trek over the Scottish mountains from Dundee to Balmoral Castle in a bid to become Poet Laureate for Queen Victoria failed to grant lasting glory.

Yet it was through his feats of determination in the face of failure and mockery, coupled with how bad his poems were, that McGonagall would earn his immortality.

In 1931, the literary critic Neil Munro related his experience in 1897 of witnessing a particularly callous prank being played on an elderly McGonagall. Invited to a literary society symposium, the ever-theatrical poet came in Highland dress, wielding a sword with which, while reciting his works, he pantomimed the act of slaying Englishmen. During the final speech of the evening, the chairman presented McGonagall with a gift of an oversized sausage adorned with ribbons. Initially offended, McGonagall was quickly reassured that it was ‘as sensible an offering to a poet as the laureate’s cask of Canary wine’. McGonagall later apologised to the organisers for taking offence, writing that it was in fact the best sausage he had ever tasted. Munro, for his part, felt ashamed to have been party to this mean trick.

Similarly, in a 1947 essay, the writer and scholar Lewis Spence fondly remembered how, at the age of 17, he met McGonagall and immediately became enamoured with his ‘natural eccentricities’. Spence insisted that despite the poet’s delusions of grandeur he was a thoughtful and gentle man, which made watching audiences hurl insults at him painful. Spence admitted that, while the unintentional hilarity of the poems still tickled him over 50 years later:

William McGonagall was no freak, no mere buffoon ... when I think of his courage, displayed in such circumstances of public contempt and misunderstanding as few men have to endure, I feel that his memory should, at the least, be protected from ignominy.

In death, McGonagall’s renown as a comically bad poet has only grown larger, in part due to writers such as Munro and Spence continuing to resurrect his work for new generations. For all his foibles, McGonagall could be considered a postmodernist visionary who, however inadvertently, foreshadowed how art movements of the 20th century would seek to deconstruct ideas around artistic validity. When contemporary critics dubbed him the worst poet in history, they could never have predicted that over 100 years later, countercultural filmmakers such as John Waters and Tom Green, deliberate purveyors of the glorious vulgarities of kitsch, would view such condemnations as a badge of honour. Nor would they have expected McGonagall himself to become a cult figure, whose poems make frequent cameo appearances at Burns Night celebrations. As an ironic antidote to the verse of Robert Burns, McGonagall’s rhyming of ‘fine’ with ‘sublime’, never fails to bring the house down. Some Burns Night suppers have even been dedicated solely to McGonagall, one notable instance being in 1982 as part of a fundraiser for the Dundee Rep Theatre after its destruction by fire. The comedian Billy Connolly recited his poems to an audience of around 300, all dressed as McGonagall with bonnets and shawls. His fan club has continued to thrive into the 21st century. In 2008, a signed collection of his poems fetched £6,600 at auction, surpassing that of a Charles Dickens first edition.

On the question of why supposedly bad art can be so beloved, the Museum of Bad Art’s co-founder, Marie Jackson, has said that to enjoy bad art is to appreciate the human ubiquity of failure. It may be that the affectionate feelings evoked by McGonagall’s poetry reflect our own relationship with failure, to which we can relate far more than the idea of prodigious success. It is a shame that McGonagall never saw how his poems would bring such joy to others, but perhaps his talents were destined to only be truly understood posthumously.

Ellen Walker is a freelance writer and illustrator, and a PhD researcher at the Royal College of Art in London.

Source: History Today Feed