An Edict of Toleration | History Today - 2 minutes read

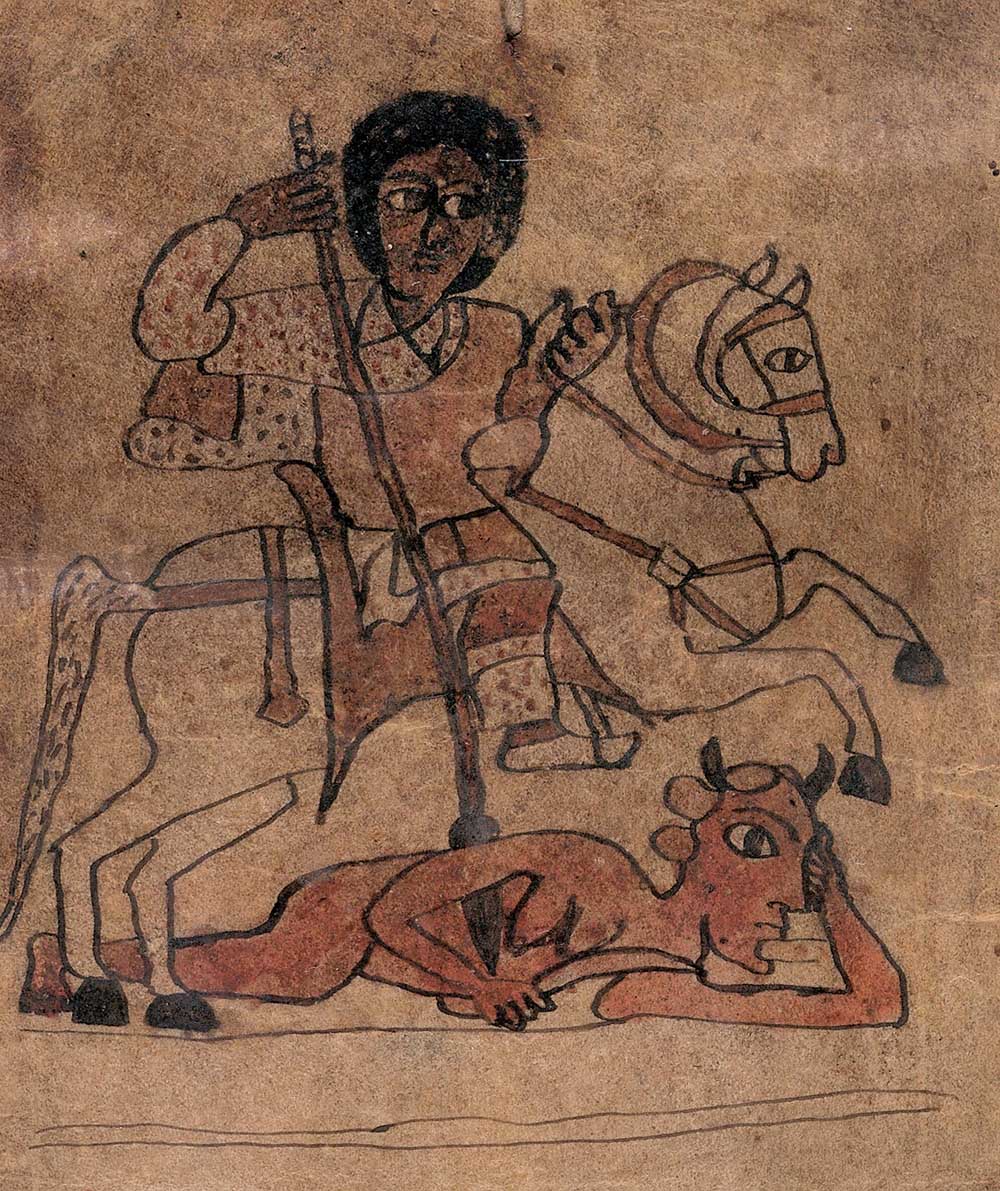

When the Jesuits arrived in Ethiopia in 1557 they encountered a Christian society whose antiquity rivalled Rome’s. The region had converted in the fourth century; its royal family claimed descent from the queen of Sheba. But it followed the teachings of the Alexandrine Church; from Rome’s perspective it had been apostate since the Council of Ephesus in 431.

The missionaries found a convert in Emperor Susenyos, who took power in 1607. For him, they offered restoration of Christianity’s purest form. ‘This faith did not arrive to us sailing’, he said. ‘It is the faith of our old fathers and of … the Nicea Council.’

Susenyos hid his conversion until 1622. Meanwhile, the Jesuits targeted Ethiopian practices regarding the Sabbath: fasting, divorce and much else. Circumcision, a rite of passage into adulthood, was ubiquitous; it horrified them.

To the locals, the missionaries were ‘Franks’ or, worse, ‘sons of Leo’ – after the fifth-century pope – and ‘relatives of Pilate’. Susenyos himself was a ‘black Portuguese’. Wherever Jesuits preached, people said, a plague of locusts followed; they made the host from animal dung.

From the late 1610s there were rebellions. A new head of mission, Afonso Mendes, made things worse. Mendes had a fondness for pomp and his own voice: his first address to the court in 1626 ran to 30,000 words. By 1629, even he could see little hope: ‘The prophecies foreseeing our death are so numerous’, he wrote, ‘that if only one of them was to become true we would all be finished.’

As the decade turned, Susenyos had only a few secure provinces left. One last battle in 1631 saw a 25,000-strong rebel army defeated, but, surveying the thousands of dead, he realised the cost was too high.

On 14 June 1632, Susenyos abdicated in favour of his son. ‘Let the people have their own altars for the sacrament and their own liturgy, and let them be happy’, he said. He died three months later, worn out by war, in the comforts of the faith that had cost him his kingdom.

Source: History Today Feed