Removing That Little Knot | History Today - 18 minutes read

Using chloroform, scissors and a hot iron, the surgeon Isaac Baker Brown sought to cure the nervous conditions and emotional disorders of middle- and upper-class Victorian women. At his clinic in Notting Hill, west London, he excised the clitoris, an operation in which he claimed to be a modern pioneer, urging all medical men to adopt this surgical intervention to cure certain forms of mental illness. When the highly private nature of his work escaped into the public domain during a notorious divorce case of January 1867, the Lancet and the British Medical Journal (BMJ) lined up to condemn this ‘dreadful operation, performed upon married women without the consent of their husbands, and upon married and unmarried women without their own knowledge of the nature of the operation’. Brown found himself with few supporters and, while the revulsion at his activities could be viewed as a victory for women’s rights, an examination of the opposition to clitoridectomy reveals a more complex set of cultural beliefs in the middle of the 19th century.

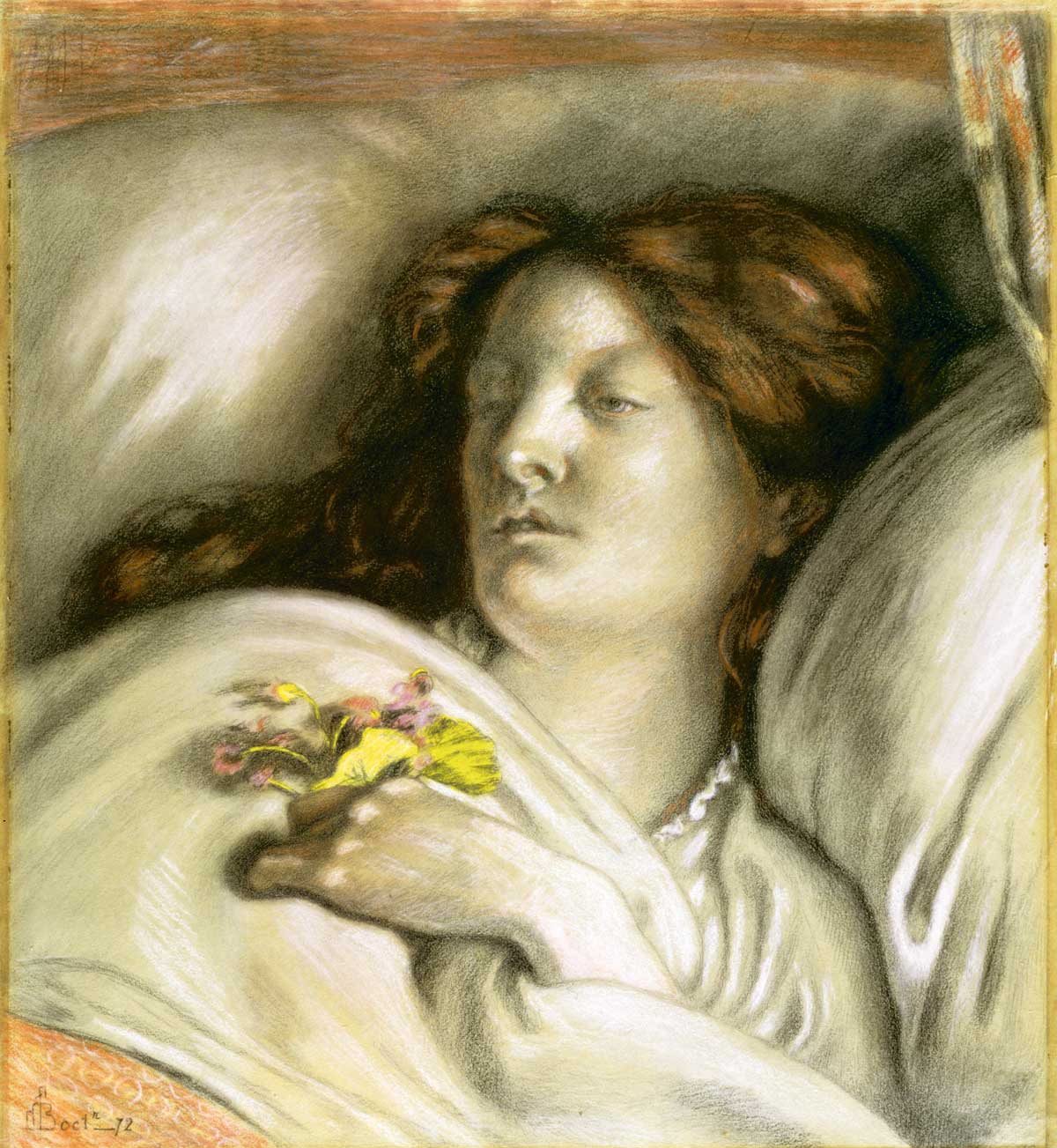

On 25 January 1867, the Divorce Court began hearing a case brought by the siblings and in-laws of Mary Ann Hancock. They claimed that Mary Ann’s marriage to Robert Peaty, three and a half years earlier, should be annulled on the grounds that she was insane at the time the marriage was contracted. (A ‘lunatic’ was not deemed to be capable of consenting to marriage.) This was an unusual proceeding – and the nation’s newspaper reporters were in court to note down every detail. One of the strangest aspects of Hancock v Peaty was that man and wife were still in love and did not wish to be torn asunder. The couple both admitted that Mary Ann had been confined in an asylum for short spells after her marriage; but they claimed that she had been sane throughout their four-year engagement and, crucially, at the time of the marriage ceremony. But witness after witness came forward with lurid accounts of the behaviour that Mary Ann exhibited one week of every month before being wed. Coy references in court to a menstruation-linked mood disorder included ‘periodic bouts of unsoundness of mind’, with ‘uterine irregularities’, ‘nymphomania’ and ‘hysteria’. Yet everyone (except the Hancock siblings) agreed that for three weeks out of four, Mary Ann knew a hawk from a handsaw.

Robert Peaty, a Bank of England clerk, had known Mary Ann from adolescence. They had been in love since the age of 17 and, knowing of her occasional oddities (her ‘excitability’ is how he described it), he had consulted two doctors. He wanted to know if marriage, intercourse and childbirth might cause her distress, worsening her condition. Also, he wondered, was she of sound enough mind to consent to marriage? One doctor said marriage would be a good idea for Mary Ann and was likely to calm her. The other worried that marriage could exacerbate her nervous disorder. Neither said she was unfit to give her consent.

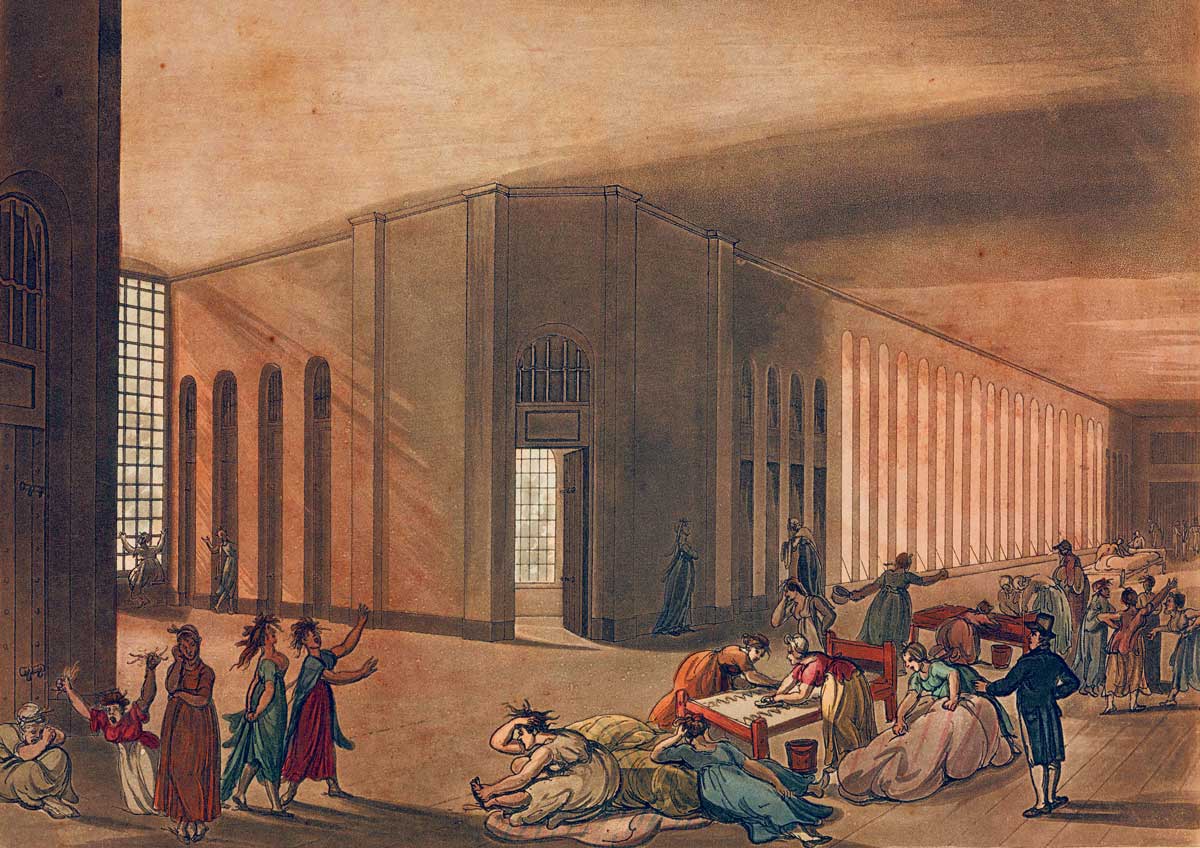

After the wedding, the ostracism of Mary Ann by her immediate family caused her to break down entirely and Robert reluctantly had her signed into St Luke’s insane asylum at Old Street, London. At the Divorce Court hearing, Robert made it plain that he believed her sisters and their husbands were acting in bad faith to have the marriage annulled; it was Mary Ann’s legacy from her late father that they wanted to gain control of, he said – and this was legally impossible while she had a husband. He went so far as to state that the Hancocks had put Mary Ann’s mother into an asylum when she was not insane, simply ‘for their convenience’. He claimed that Mary Ann was unlike her sisters, being ‘a lady’, ‘superior’, able to sing and play music, ‘educated’ and ‘sensitive’; she had lived the life of ‘Cinderella’ with her sisters, he claimed.

Cause célèbre

Hancock v Peaty was already a national cause célèbre when, on the fifth day of the hearing, it was revealed that the sisters had had Mary Ann admitted to Mr Isaac Baker Brown’s 34-bed London Surgical Home (at 18 Stanley Terrace, Notting Hill) to have her condition cured by clitoridectomy.

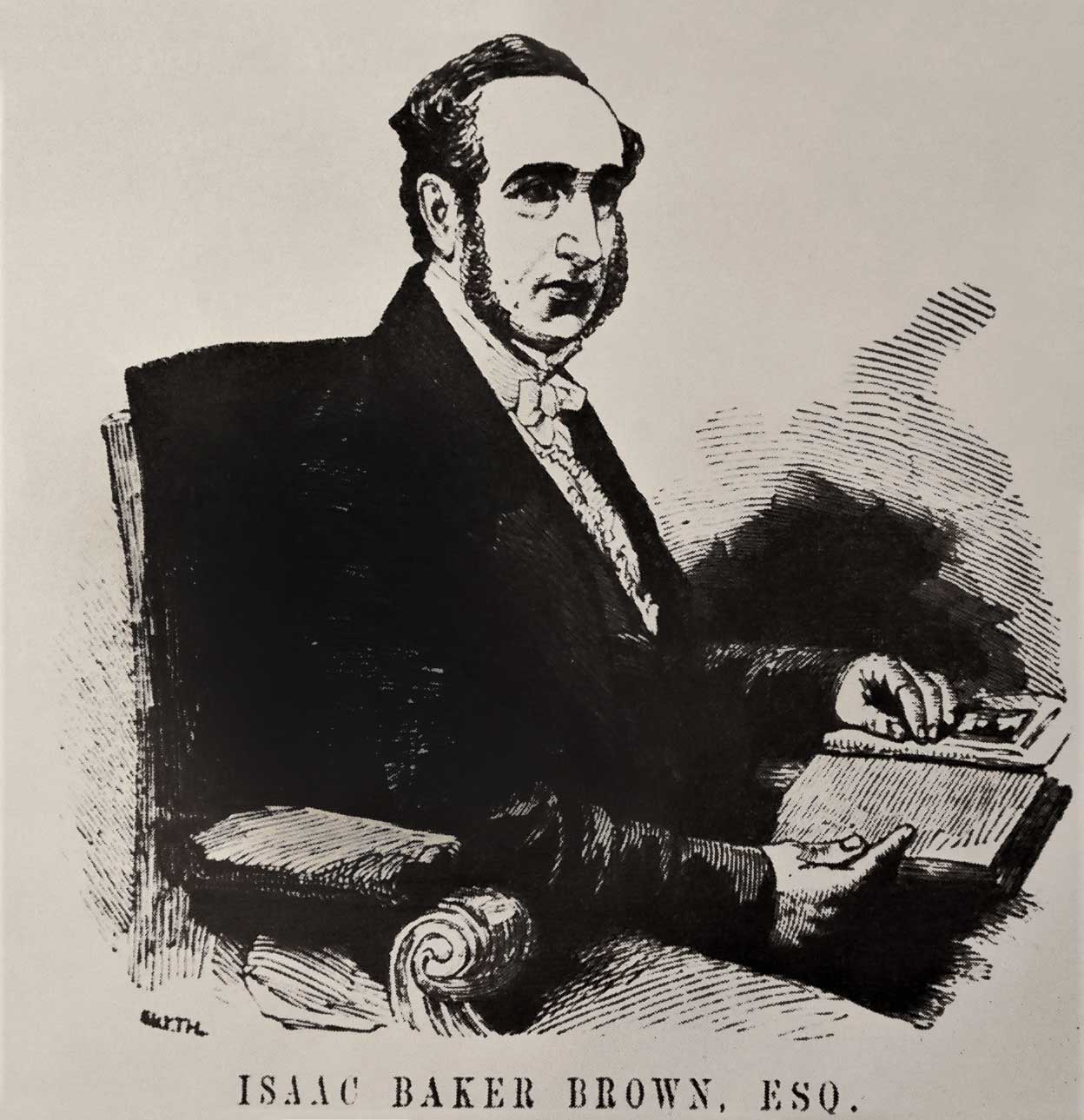

Brown was celebrated for his work on prolapses, fibroids and anal and vaginal fistulae and had pioneered a significant advance in ovariotomy. In 1865 Brown’s reputation was at its peak as he published his book The Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy and Hysteria in Females, advocating clitoridectomy.

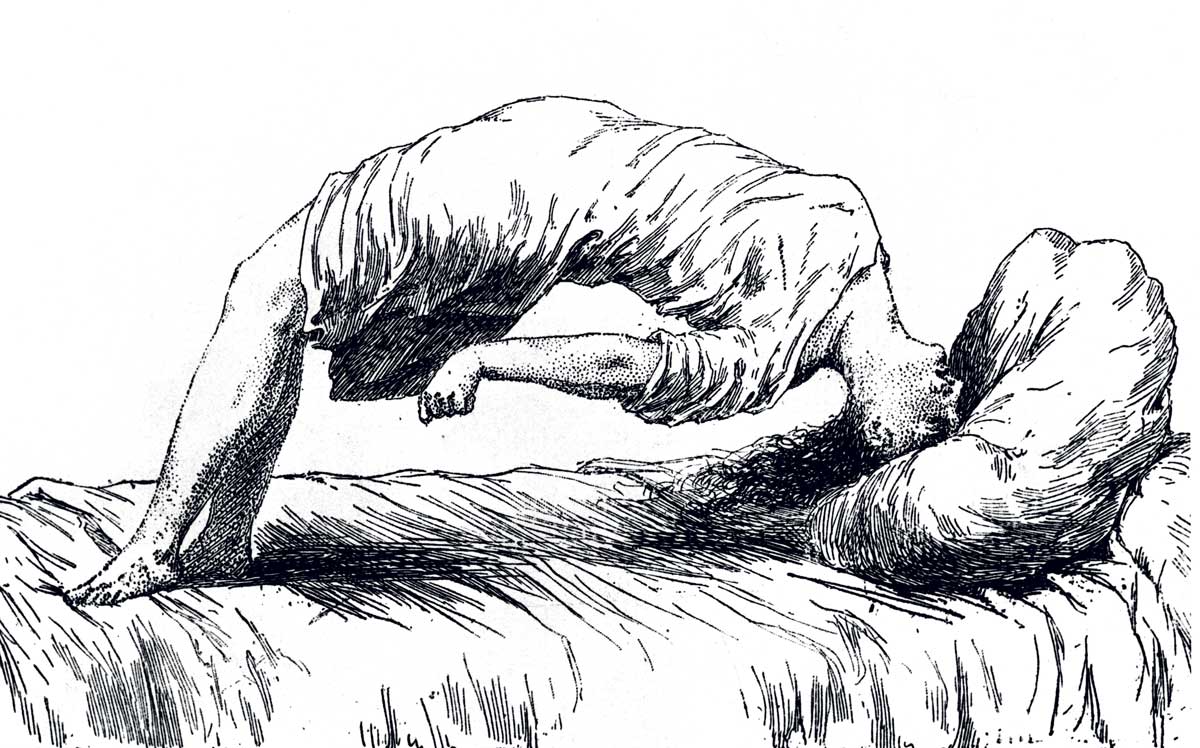

His first clitoridectomy, he wrote, had been performed on 12 October 1859 on ‘DE’, aged 26, an unmarried dressmaker living in Yorkshire. She had for five years suffered irregular periods, constipation, poor appetite, nausea after eating, lower back pain, weakness and melancholy. ‘This being my first operation, I did not know the consequences of performing it.’ She recovered after two months and he claimed she had been in excellent health in the six years since.

‘Mrs R’, aged 42, a childless widow working as a lady’s companion, had for six months suffered great pain in the lower abdomen, a burning pain in the vulva and an irritable bladder. She had developed insomnia and said she was experiencing ‘a sort of lost feeling, particularly when writing, being unable to compose her thoughts or concentrate her mental energies’. Brown wrote that she occasionally had ‘an appearance almost of insanity about her expression. There is ever evidence of a long-continued inhibitory influence’ (that is, masturbation). He performed a clitoridectomy upon Mrs R on 7 August 1862 and two days later wrote: ‘Is improving wonderfully – the expression of countenance completely changed.’ A month later he approvingly noted weight gain and stated: ‘has now a cheerful face and manner. Says she feels a different being’.

One of the few ‘failures’ is entered in his book as a fraud and ‘an imposter’, though he supplied no evidence of why he came to this conclusion: ‘HD’, 23, had been epileptic from the age of ten. At 19 she became ‘hysterical’ and spoke endlessly about religion; and there was ‘evidence of continual irritation of the pudic nerve’ (masturbation). He operated on 3 April 1862 and later decided that she had been seeking attention, only pretending to be a ‘nervous patient’. ‘She was discharged as incurable. This case I have inserted as a warning. It is no fault of the operation if it fail in such cases.’ He gave himself the perfect excuse: any clitoridectomy that did not work was the result of the patient being a fraud.

A dirty subject

The British Medical Journal and the Lancet both attacked The Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, stating that its main premise (that masturbation, or ‘peripheral excitement of the pudic nerve’, caused a range of mental illnesses in women) had no basis in physiology. This was not evidence-based medicine. Moreover, the BMJ pointed out, Brown’s book had been luxuriously published, with gilt lettering proclaiming the subject matter on its front cover and spine, and looked ‘like the class of works that lie on the drawing-room table’ (what we would call ‘a coffee-table book’). Thus, according to the BMJ, Brown risked bringing into the public domain matters that should remain within doctors’ consulting rooms: ‘It is a dirty subject ... It needs to be handled with an absolute purity of speech, thought and expression, and as far as is possible, in strictly technical language.’ For its part, the Lancet declared his operation ‘a proceeding which if it be useless is a lamentable mistake, and if it be unnecessary is a cruel outrage’.

Brown maintained that masturbation gave rise to disease that progressed through the following stages: ‘hysteria, spinal irritation, epileptoid fits/hysterical epilepsy, cataleptic fits, idiocy, mania, death’. The symptoms that revealed that the pudic nerve was being regularly ‘over-excited’ through masturbation included: restlessness then excitability, then melancholy, then listlessness; indifference to social and domestic life; fussiness about food; hypochondria; dry skin; dilated pupils and moist palms.

Following the BMJ’s hostile review, its letters pages featured many complaints from medical professionals about Brown’s operation and its theoretical underpinning – or lack thereof. Many doubted the extent of female ‘self-abuse’. Dr Henry Maudsley himself wrote to claim that he had only ever known one case of insanity caused by self-abuse and this had been one in which Baker had performed a clitoridectomy and the patient had not improved. Maudsley, at this stage of his career at least, saw the forced dependence of women upon men as ‘a fruitful source of insanity among women’, and being brought up to be fit for nothing but marriage led to madness: ‘the evil effects of an ill-trained mind thrown back upon itself’. There was no surgery that could change that state of affairs.

Throughout 1866, the Lancet’s letters pages also seethed with condemnation. The surgeon Harry Page Moore of Ipswich wrote that he was at that time helping a 26-year-old woman to recuperate from the ‘horror and indignation’ of having had a clitoridectomy at the London Surgical Home. The epilepsy for which she had been treated had initially seemed to improve ‘but a month had not passed before her fits returned with a severity never before equalled, and she is now as bad as ever’.

Dr Charles West wrote to the Lancet to state the following: masturbation ‘irritated the pudic nerve’ no more than sexual intercourse itself; girls were less likely to indulge in masturbation than boys; in any case, no link had ever been proved between epilepsy and masturbation in either sex – or with any kind of nervous disorder; clitoridectomy had never been proved to produce permanent cure; in fact, he knew personally of several instances where the operation had caused ‘very mischievous results’.

Dr Thomas Littleton wrote that men who behave as Baker Brown did were the ‘type’ of man who approved of tyranny towards a wife. Dr Sisson of Maida Hill, west London, wrote that ‘for every diagnosis, this operation is useless’. Henry Gage Moore wrote that one of Brown’s patients had been just seven years old when she became an epileptic and so her condition could not have been caused by self-abuse.

Moore’s letter to the Lancet also revealed that other techniques included the use of ‘caustics’ – blistering chemicals applied to the clitoris to reduce or damage its nerve endings; preferable to ‘total extirpation’, in Moore’s view. Why, Moore asked, if clitoridectomy worked to end masturbation, did Brown insist that observation of the ‘cured’ patient should continue? Brown had stated in his book: ‘It cannot be too often repeated that this improvement can only be made permanent, in many cases, by careful watching and moral training, on the part of both patient and friends.’ In sum, Moore put it this way:

We have scarcely more right to remove a woman’s clitoris than we do to deprive a man of his penis … I am very sorry that females have not as much knowledge of the clitoris as we have, for if that were the case, I am sure there are very few who would consent to part with it, and when questioned about it afterwards say, ‘Oh, I have only had a little knot removed’.

‘A Provincial FRCP’ wrote to the BMJ alleging that Brown was a relentless self-publicist, expert at drumming up business by sending London Surgical Home promotional material to ‘half the nobility in the kingdom’ – although documentary evidence does not survive to back up this allegation. At the end of 1866, Brown persuaded The Times to run a favourable report about his clinic, boasting of its pioneering work in helping troubled women – though without actually naming the operation.

It is likely that it was word-of-mouth that led certain wealthy families to suggest a visit to the Surgical Home to their odd, difficult or depressed womenfolk. Presumably this is how Mary Ann Hancock’s sisters had heard of the operation and arranged her admission.

The seat of delectation

In his book, Brown had anticipated criticism that removing the clitoris would ‘unsex the female’, as he put it, rendering her neuter in a highly gendered society. Excision would not ‘prevent normal excitement on marital intercourse’, he wrote, which suggests that Brown did not fully appreciate, or perhaps did not approve of, the organ’s role in producing pleasure. The 16th-century Italian anatomist Realdo Colombo had been the first to state unequivocally that pleasure was the sole function of the clitoris (‘the eminent seat of delectation in women when they engage in venery’). Most anatomists agreed. Views were expressed during the Baker Brown scandal that the pudic nerve to which the clitoris is connected also made the vagina and the anus susceptible to sexual excitement; nevertheless, the dominant view by mid-century remained that ‘the clitoris is the seat of pleasure during coitus’, as Robert Thomas had written in his still-influential work of 1801, The Practice of Physic (which went through many editions across the first half of the century). It is difficult to understand why Brown would so blithely argue that desire and satisfaction would be completely unaffected by the organ’s removal. Perhaps it was because he knew that his patients and their relatives would themselves have no idea of what the clitoris really was.

In March 1867, John Locking, a consulting surgeon at the London Surgical Home, resigned when he could not prevent Brown undertaking a clitoridectomy after he had said that he would cease performing the operation until the controversy over his work had died down. Locking and another staff member gave details of Brown’s casual approach to obtaining consent to the operation from the patient and her relatives. Robert Peaty himself told the Divorce Court: ‘I am even now in the dark as to what the operation was that was performed upon her … it was always a secret to me the complaint of disordered functions under which she laboured.’

This cavalier attitude towards consent fed the growing alarm that Brown was a rogue element in the London medical fraternity – egotistically striking out alone and refusing to conform to any code of conduct. It is important to bear this in mind as an exacerbating factor in the growing opposition of the professional body, the Obstetrical Society, towards him: chivalry; concern for ‘the gentle sex’; and anger that a woman’s ‘natural protector’ (the male in her life) was being ignored by the surgeon were equalled by professional indignation at this upstart who appeared not to care for the rules.

Illegal practice

The year-long furore in the press roused the attention of the Commissioners in Lunacy, the government inspectorate for the asylum sector and ‘lunatic’ patient care. Brown’s boast was that he cured certain forms of insanity using surgical intervention; but this had no standing in English lunacy law. His clinic had been admitting women with psychological problems but he had not registered the London Surgical Home as an asylum, as legally required. Brown now denied that he had ever operated on anyone of unsound mind, yet his book stated the very opposite. The clincher was Hancock v Peaty, where everyone agreed that Mary Ann had been subjected to Brown’s scissors precisely because she suffered a mental illness. In a series of unconvincing letters to the Commissioners, he claimed that he had not been aware of the legal need to register his clinic as an asylum if it were to admit ‘lunatics’.

Lack of informed consent was another major criticism of his operation. By the time a woman had been delivered for mutilation, she and her family were at a huge disadvantage: the very act of being treated by Brown compromised the character of a ‘lady’ and her family. One hostile doctor claimed that Brown charged fees as high as £200 per operation from husbands and fathers in his waiting room, fully aware that they would pay up in the face of the unspoken accusation that ‘your daughter, or your wife, has undergone a disgraceful operation because she has been given to disgraceful practices’. The BMJ called Brown’s hold over these elite families ‘terrorism’, which was ‘used to frighten a patient into submission where need for operation there was none’.

The Lancet also picked up on the way that such an unfounded theory as Brown’s could be used to whip up a sense of shame that might persuade a parent, guardian, or family member to try the surgeon’s method.

This much ... may be now feared – namely, that this work [Brown’s book] may create a tendency to regard nearly every case of epilepsy or hysteria occurring in a female, a young unmarried girl especially, as due to ‘abnormal irritation of the pudic nerve’, and that there will be found persons whispering into parents’ ears, deeply wounding the sensitive nature of delicate young females by such allusions.

In 1867, a savagely satirical 16-page pamphlet was privately published and circulated: The London Surgical Home; or, Modern Surgical Psychology, by the professor of forensic chemistry John Scoffern, mocked the idea that the cure for a psychological phenomenon lay in surgically modifying the organ to which it was linked. In Scoffern’s spoof, Baker Brown’s clinic was where ladies who shoplift in department stores had the tendons in their fingers modified to prevent such pilfering; ladies who gossip too much have their tongue operated on; and ladies who want to dance at balls every night (‘waltzing mania’) have modifications made to their leg muscles. In Swiftian mode, Scoffern attacked the vicious stupidity of Brown’s anatomical interventions in human behaviour.

Scoffern himself lived, coincidentally, close to Stanley Terrace, so it is tempting to see the following passage, though highly facetious, as an eyewitness account:

A veil of mystery has been thrown around this beneficient home [despite] the comfort, nay splendour, of the equipages which daily throng it. Carriages may be seen to draw up, and delicate girls descend, accompanied by their parents or nearest guardians; any day, pale female forms may be seen to emerge; serene and tranquil. These are the patients who have been subjected to the masterly treatment of Mr Baker Brown ... They go in, these patients, to be operated upon; they come out cured, few but themselves the wiser for what has happened.

The lady whose hand has been operated upon to prevent her shoplifting will still wave gracefully, look good in gloves, play the piano moderately well – she will be ‘very refined, though somewhat listless and unimpulsive’. In this way, Scoffern captures the sense of a human being having her vitality robbed in pursuit of being made more acceptable within bourgeois family life. The ‘epoch of surgical psychology’ (as he named it) had deeply sinister implications, unknowingly anticipating the criticisms of lobotomy, which would commence 70 years later.

Eight years earlier the Lancet had reported with alarm a US experiment in which six epileptic black men had been castrated in an attempt to cure their epilepsy. Not for the first or last time, experimentation without informed consent took place upon a group with significantly less social power than the medical scientist. The English doctor John W. Ogle wrote to the Lancet explaining that he had turned down a request by a patient of his ‘of degrading and debilitating habits [which] commenced when he was 10 years old’, who had heard of this, ‘the Tennessee Experiment’, and wished to be cured in this way. Ogle refused, stating, ‘I could find no trace of any aura commencing in the testis’ and doubting that the Tennessee victims had in fact ceased to have epileptic fits post-castration.

Dr Seymour Haden of the Obstetrical Society stated: ‘Clitoridectomy is quackery ... either he [Brown] cured these people, or the whole thing is a sham.’ On 3 April 1867, the Society overwhelmingly voted for his expulsion, following a long and stormy meeting.

And that was the end of Isaac Baker Brown. He survived on the charity of his remaining supporters, who sent him money and bought him a six-piece silver dessert service from Benson’s of Bond Street, engraved: ‘In appreciation of his marked surgical skill and singular success in the treatment of female diseases.’ He suffered a series of ‘paralytic seizures’ and his final year was spent in ‘a helpless state’, according to the Lancet. He died, aged 61, in 1873.

It was chivalry rather than feminism that saw off mid-Victorian clitoridectomy. In Hancock v Peaty, part of the scandal was that Robert, as much as Mary Ann, had not been asked consent for ‘a most cruel ... barbarous operation upon her’, as the BMJ put it. Women had to be protected from even hearing about such a ‘dirty’ subject as masturbation and men were obliged to carry out their protective duty in this regard. If men were to deserve the exclusive prestige of becoming medics, they had to be seen to fully deserve it.

As a tragic coda, the Divorce Court found that Mary Ann had not been well enough to consent to marry and her marriage was forcibly dissolved. Robert continued working for the Bank of England and died in 1882. Mary Ann died aged 79 in 1906. The archives do not reveal the extent to which the couple may have managed to maintain a loving, common-law relationship. Like Baker Brown, they moved from notoriety to oblivion.

Sarah Wise teaches at City University and is the author of Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad-Doctors in Victorian England (Bodley Head, 2012).

In addition to the information offered here, I will introduce you online. This is an excellent collection of games I've played, featuring some of my all-time favorites and most well-known titles. Another subject. Various games that I believe you will enjoy. retro games