Empire and Celebrity | History Today - 17 minutes read

On 7 November 1777, a letter in the London Morning Post described a ‘strange monster’ being driven in a phaeton along Fleet Street.

Notwithstanding the creature cannot be old; its eyes looked something like those of a dead cod, – its mouth rather large, and it grinned not to laugh, but to shew its teeth, which appeared tolerable white. … The only thing it moved was its lips and head, which it turned from side to side, and seemed to stare at the people with an unmeaning, cold, contemptuous look, as if they were creatures below its notice.

Grinning and grotesque, the ‘phenomenon’, the letter reported, travelled slowly, ‘as if to give time to the spectators to examine it’. It suggested, the writer thought, ‘something of the human species in its figure’, but its face was painted and it wore a complicated tower of hair and a long cape covered in gold lace. Passing coach passengers and ‘gazers’ reacted with ‘amazement, indignation, contempt’, speculating that it might be ‘one of the new animals brought home by some of your curious voyagers; who, as is said, have crossed round the world’.

After all this, though, the letter-writer provides the punchline by suggesting, slyly, if the wonder may simply have been ‘a young person of fashion of these times’. The letter, it becomes clear, is one of the many contemporary satires on a generation of privileged young people believed to be desperate for fame for the sake of fame. Like many future commentators on what is now called celebrity culture, the writer is disturbed not only by the way that young people reject his ideas of gender and beauty, but also by their apparent ambition to make an ‘unmeaning’ spectacle of themselves in public.

In the 21st century, most of us are used to this paradox: that a celebrity can be both a stranger – someone who probably considers us ‘below notice’ – and as familiar as our friends and family. Celebrities are still visible enough to have their teeth, hair and eyes inspected by strangers, not now in phaetons but on billboards, screens and magazine pages. Theorists of celebrity present and past point out that this apparent intimacy coexists with the unreachable mystery of the star. This can still seem absurd today, as we produce our own strange monsters, but the idea that fame could be the reward not of rank or achievement, but of scandal, eccentricity or assiduous self-publicity, baffled many 18th-century Britons.

Absurdities of the bon ton

Mentioning the natural history specimens being collected on James Cook’s Pacific voyages, the letter imagines celebrity culture as an exotic import or novelty. Yet, since the Restoration at least, the British public had ‘known’ the faces and bodies, characters and scandalous personal lives of actors and actresses, Nell Gwyn, Anne Bracegirdle, Colley Cibber and David Garrick among them. The late 17th and 18th century saw popular crazes for individual musicians, dancers, singers, murderers, conmen, politicians, fashionable courtesans, boxers, preachers and authors (‘I wrote not to be fed but to be famous,’ Laurence Sterne once admitted).

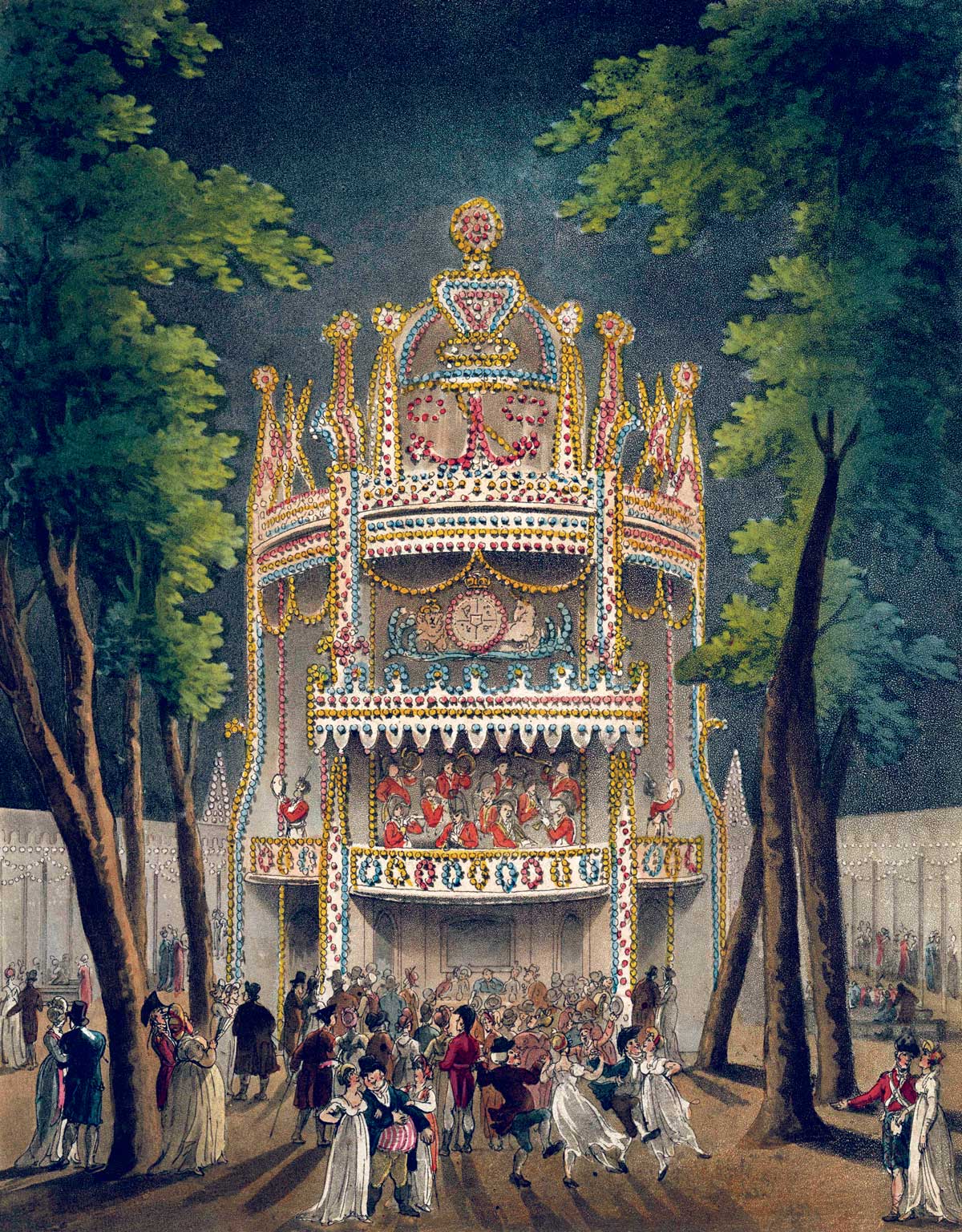

As the size and variety of British newspapers and other forms of print media increased in the 1760s and 1770s, the scale of these crazes grew. Engraved portraits were increasingly common and affordable, allowing famous faces to circulate more widely. A new cultural economy of gossip and hype developed in the pages of newspapers – especially the notoriously scurrilous Morning Post. At the same time, elite British styles of hair and dress were reaching attention-seeking new heights. A proliferation of new public spaces and buildings opened, seemingly designed for showing off in: pleasure gardens, masquerade balls, theatres and concert halls in London and beyond allowed any audience member to become a performer. In the theatre, fame-hunting was depicted through the excesses of satirical characters like Lady Bab Lardoon (‘complimented one day, laugh’d at the next, and abused the third; you can’t imagine how amusing it is to read one’s own name at breakfast in a morning paper’), or the happily married Harry and Harriet Trifle, who plan to divorce just to cause a newspaper scandal. As the hero of the stage comedy Notoriety explains, nowadays anyone who ‘makes a damn’d noise without any meaning’ can be famous like him.

Beyond the absurdities of the bon ton, though, emerging celebrity culture offered to a handful of ordinary men and women a route to social and economic mobility. To many more people it provided a new sense of being part of a national community, in which strangers who would never meet were connected by their shared knowledge of names, faces, gossip, catchphrases and fashions. The late 18th century saw crises in British identity provoked by transformations in its colonies and global relationships: the sudden acquisition of vast Canadian territories, the rebellion of the American colonies, revelations of corruption and injustice by the East India Company, the establishment of a penal colony in Australia and a groundswell of horror at the slave trade. In a period of change and uncertainty, celebrity culture provided new ways of imagining, selling and consuming the unfamiliar.

English heroines and Eastern despots

The Prussian traveller Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz, surveying the English public in 1789, noted that even at the tail end of her career, Frances Abington was ‘the greatest ornament of their stage, and unites all parties in her praise’. Abington was what would now be called a ‘girl next door’ type, glamorous but determinedly unpretentious. Having worked in her teens as a flower seller and in a milliner’s shop, she had climbed her way to fame playing comic women of fashion, including Lady Bab Lardoon. These roles helped her to build a public status as a friend of the aristocracy and the national trendsetter. At the height of her fame, the milliners of London and Dublin reportedly displayed signs saying ‘ABINGTON’ in their windows, enticing customers with the promise that they too could dress like a star. In 1775, Isaac Bickerstaff had written a star vehicle for Abington at Drury Lane. The Sultan, or a Peep into the Seraglio was adapted from a comedy by Jean-François Marmontel and is set in a European Orientalist idea of an Ottoman harem. Abington played Roxalana, a lively and ‘ungovernable’ English slave, whose ‘irreverent behaviour’ and insistence on monogamy, European manners and drinking alcohol reform her Muslim master.

The critical consensus in 1775 was that only ‘the uncommon merit of Mrs. Abington’ rescued The Sultan from the undeniable mediocrity of its script. The part of Roxalana, though, was central to Abington’s celebrity status. It was in this role that Joshua Reynolds painted one of Abington’s most popular portraits, showing her bursting out of the seraglio through a red velvet stage curtain. Abington regarded the part as her personal property. When Dorothy Jordan played Roxalana in a 1787 Drury Lane revival of The Sultan, Abington took the casting as a deliberate insult. The other major London theatre, at Covent Garden, promptly staged a rival production of the comedy and Abington’s Roxalana competed for weeks with Jordan’s.

In the role of Roxalana, Abington’s extraordinary common touch was made political and patriotic. Like Abington, Roxalana is down-to-earth despite her exotic wardrobe and situation, ‘a free-born woman, prouder of that than all the pomp and splendour Eastern monarchs can bestow’. She wins the sultan’s heart not because she is beautiful (other characters frequently refer to her as ordinary-looking), but by teaching him about the liberty and egalitarianism the play presents as her national birthright. England, Roxalana enthuses, is a land where would-be despots are constrained by the constitution and citizens of all ranks can speak freely to each other. As Abington’s fans in the audience might reflect, its celebrity culture also created a place in which a humble flower girl could rise to rule high society. In contrast, the ‘Oriental’ (Ottoman and Georgian) characters in the seraglio are depicted as literally in love with their own servitude, unable to think or speak for themselves until enlightened by the English interloper. The comedy ends with the seraglio liberated and Roxalana the new sultana, assured that her noisy Englishness makes her ‘worthy of empire’.

While this lesson was being taught over and over to laughing London audiences, two miles away in Leadenhall Street the British East India Company was administering its enormous and aggressive empire in India. After decades of overthrowing, destabilising and extorting Islamic and Hindu rulers, the Company was widely derided in its own country as pack of corrupt and ruthless nabobs. It faced growing demand from politicians for reform and accountability. Abington’s likeable performance as a plucky underdog in The Sultan offered a highly sanitised retelling of Britain’s history in ‘the East’, one which helped to rehabilitate the image of the Company and counter these demands. Bickerstaff’s story of white freedom and feminism versus eastern tyranny was all the more powerful precisely because it rarely seemed to take itself seriously.

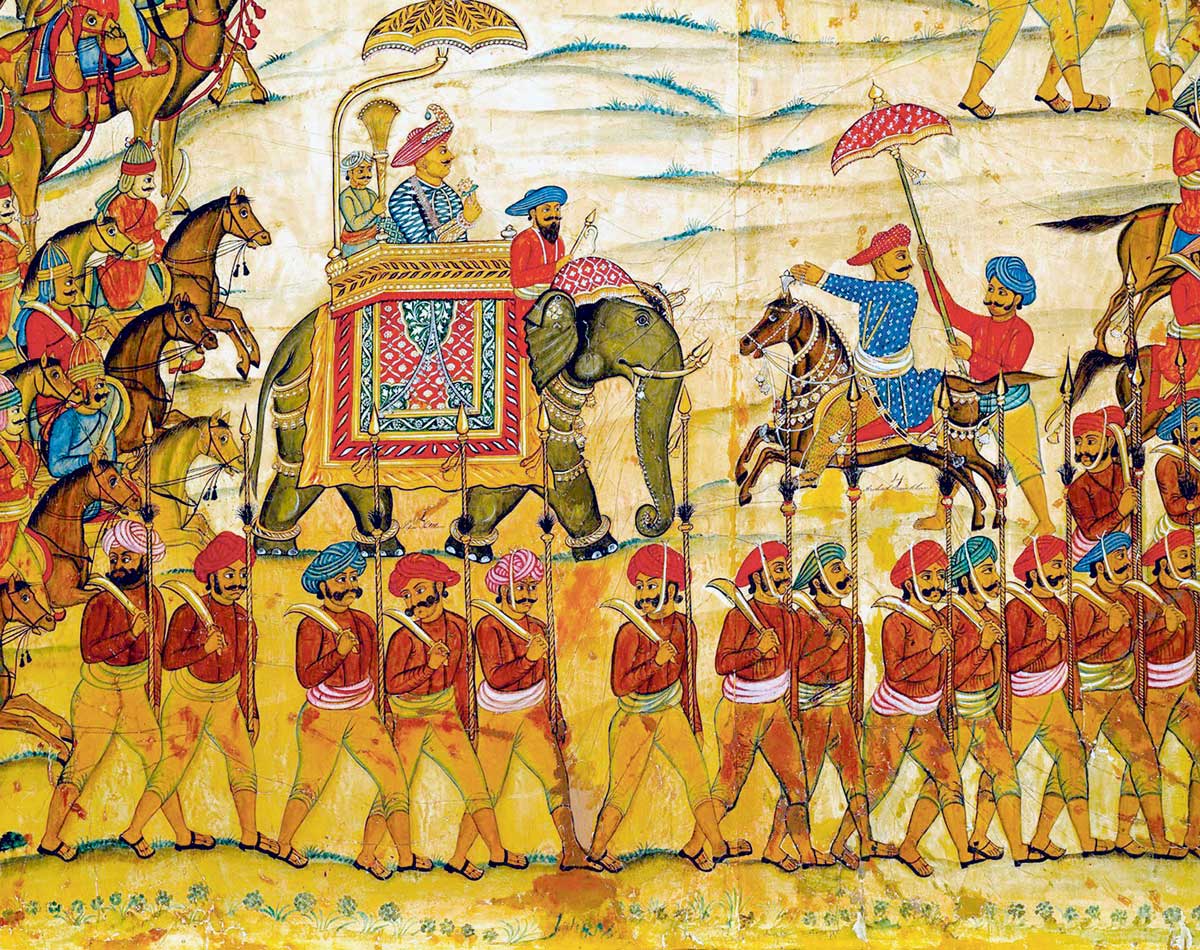

Famous foe

A person did not have to visit Britain to be put on display by its celebrity culture. In the 1780s and 1790s, for example, Tipu, Sultan of Mysore, was the Company’s most formidable military enemy but also one of the most recognisable figures in British popular culture. Stories circulated in newspapers about his many wives, the luxury of his court, his vast ambition and his alliances with pre- and post-Revolution France. In 1792, the Sadlers Wells musical Tippoo Saib celebrated – a little prematurely – his defeat, while sentimental engravings depicted the Company’s hostage-taking of his two young sons. A bigger wave of melodramatic pictures in 1799 imagined Tipu’s death in the siege of Seringapatam and the finding of his corpse in the ruins of the fallen city. The Company funded and promoted its own propaganda about Tipu, including reports of torture, forced circumcisions and the cruel executions he had ordered carried out on British prisoners. ‘Nature shudders at the thought of Indian ferocity, as of late practised in the East by the orders of that sanguinary tyrant, the Nabob Tippoo Sultan’, sobbed the Gazetteer:

‘Grant us the indulgence of an hour! – on our knees we implore it!’ – said two brave officers (General Matthews’s brother and another) – ‘No! not a moment!’ was the answer; and their throats were cut from ear to ear!

By the late 1790s Tipu’s effective if unsubtle image as a Gothic villain was so well established in the British imagination that he appeared in popular novels. In the Minerva Press’ The Beggar Girl and her Benefactors, Tipu imprisons and threatens the heroine’s father for several volumes, ‘feasts on their agonies, and drinks their tears’.

Tipu’s celebrity sometimes also reflected a more ambiguous Orientalist fascination with pleasure and luxury. ‘La Robe a la Tippoo Saib’, according to the World in 1788, was ‘a new sort among the ton’, with ‘a very long train, after the Eastern manner, of Citron green taffaty, spotted with rose colour’ and ‘a plain rose colour taffaty petticoat, cut in points at the bottom’. A printed paper board for ‘The New Game of Tippoo Saib’, now in the British Library, shows a turbaned ‘sultan’ surrounded by colourful floral motifs. As Charlotte Smith joked in her comedy What Is She?, ‘the Bengal tyger, the amours of Tippoo Saib, or some secret history of a Nabob’ all sold well. Tipu’s celebrity fitted into the Orientalist tradition of fictional and fictionalised despots – but it also confirmed this tradition and gave it a ‘real life’ figurehead. Tipu, to a British public who knew him through all this print and performance, came often to seem a figure of gossip and entertainment – a commodity to be consumed.

The wife and teenage daughter of the British governor of Madras, Henrietta and Charlotte Clive, visited Seringapatam as tourists in 1800. Although they had never met Tipu, who had died the year before, their letters and journals show an intense awareness of his presumed charisma and ‘fierceness’. The English women collected anecdotes and observations about Tipu’s life, especially about his treatment of women, and expect the readers of their letters to share their curiosity and sense of familiarity.

The Clives’ sightseeing took in the spot where Tipu was killed, where bloodstains were still visible. They went to his summer palace and gardens, and viewed his mausoleum, noting carefully that his coffin was covered with gold cloth and flowers, with a perfume censer at his feet; the room was ‘painted with the spots of the Tyger, Tipu’s usual emblems’. Visiting another of his palaces, Henrietta recorded in her journal the situation of the tiger-striped great room and ‘the room in which Tipu slept’. The result was a Roxalana-like, imperialist confidence that they knew all there was to know about the dead sultan, his family and what was best for ‘the East’. After visiting Tipu’s zenana in Company-occupied Mysore to meet his widows, Henrietta declared that, though they ‘pretended some of them to cry’, it was simply impossible that ‘they all did it sincerely’.

Celebrity and the slave trade

Earlier in the century, another of Bickerstaff’s Drury Lane comedies had given a famous face to more overtly racist ideas. The Padlock is a romantic comic opera set in Spain and from its first performance in 1768 its break-out success was an enslaved black character called Mungo. The opera’s white composer Charles Dibdin originally played Mungo, in blackface and using a voice which exaggerated the accents, and burlesqued the oppression of the many real Afro-Caribbean people living in Europe:

Dear heart, what a terrible life am I led!

A dog has a better, that’s shelter’d and fed:

Night and day, ’tis the same,

My pain is dere game;

Me wish to de Lord me was dead.

The mostly white audiences at Drury Lane loved Mungo. The production ran and ran. The Padlock’s libretto went into many editions, engravings of Dibdin as Mungo were published and masqueraders dressed in Mungo costumes. The character’s catchphrase, ‘Mungo here, Mungo dere, Mungo ev’ry where’ (a play on his pronunciation of ‘must go’) became briefly ubiquitous. Like Abington and Roxalana, Dibdin and Mungo made each other famous. There were complaints that audiences who spotted Dibdin in the theatre during other productions would heckle until he performed a song in character as Mungo. Dibdin even named his eldest son Charles Isaac Mungo Dibdin, after himself, Bickerstaff and their most profitable character.

Mungo was intended to appeal to audiences by combining pathos and broad comedy. In The Padlock he is by turns an endearingly naive clown and a lazy rebel. The comedy was first staged around the time that debates over the morality of the slave trade were beginning. Both sides of the character closely reflected and reinforced racist accusations about African men already being asserted by slave traders and plantation owners. Mungo embodied the double stereotype of the African slave, at once a helpless child who needs paternalist protection and a brutal savage only interested in drinking and dancing, who must be whipped into submission. Either way, however loudly the audience pities the clown or laughs at his jokes during the play, Mungo ‘mungo’ where he is told: his enslavement is inevitable. In the final scene, the white characters are given happy endings and Mungo is threatened with another beating.

The comedy’s veneer of good humour and sentimentality made this pro-slavery message seem harmless and detached from real life. Predictably, though, Mungo and The Padlock rapidly gained fans from touring productions in North America and the Caribbean. Perhaps less predictable was the later appropriation of Dibdin’s celebrity by campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. In 1787, the Gentleman’s Magazine published an epilogue to The Padlock in which Mungo addresses his audience directly: ‘Tank you, my Massas! have you laugh your fill?’ he asks, before dropping the ‘black’ voice and asking them to ‘let me speak, nor take that freedom ill’. His speech concludes:

O! sons of Freedom! equalise your laws,

Be all consistent – plead the Negro’s cause;

That all the nations in your code may see

The British Negro, like the Briton, free.

Of course, this epilogue, by a white British clergyman, can also be seen as another paternalist, if well-intentioned, act of blackface.

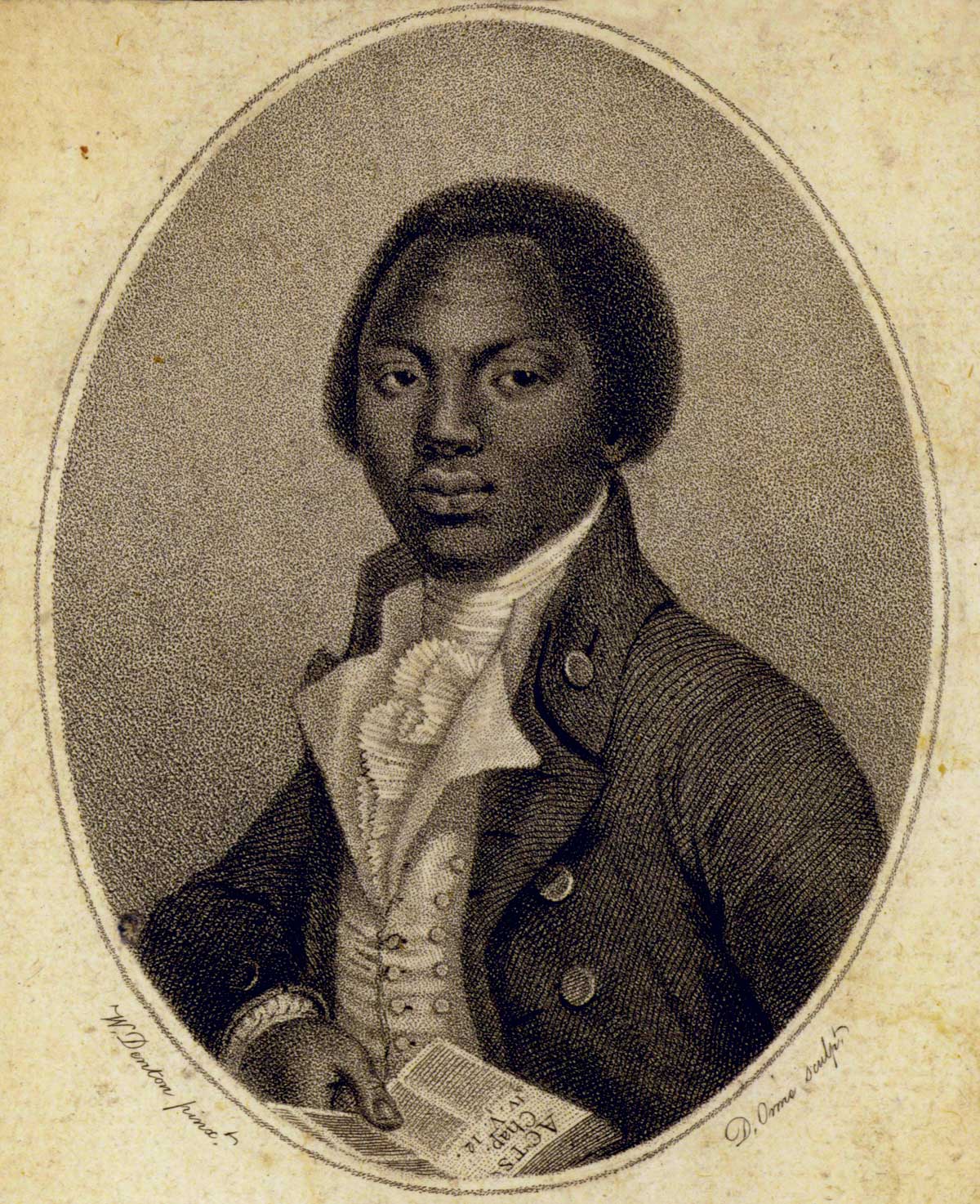

A citizen of the world

The satirical letter in the Morning Post which began this article shows, however, one way that 18th-century celebrity could genuinely amplify black voices. The letter is one of a series signed ‘GUSTAVUS VASSA’, and has been identified by Vincent Carretta as likely to have been written by Olaudah Equiano, a formerly enslaved man of Igbo descent. Equiano, who also used the European name Gustavus Vassa, was newly living in London in 1777. In 1789 he would publish an abolitionist autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African.

In his other open letters, Equiano presents himself as having the perspective of what Carretta calls ‘a citizen of the world, a man without a country’. This gives him a rhetorical authority to speak to the public directly about questions of colonialism and empire, as well as cultural issues like celebrity. His open letters advocate the abolition of the slave trade, but also the more forceful suppression of the American Revolution. Britain, he writes, should aim for ‘dominion of the seas, and the possession of islands, which are the grand and leading avenues to the East Indies, South Seas, and West Indies’.

Over several years, writing for London newspapers allowed Equiano to build his public visibility, which would later help him to sell his book and promote the abolitionist cause. As his satire suggests, this was risky. It exposed him to potential ‘amazement, indignation, contempt’, especially as a black participant in a celebrity culture saturated with images of Tipu, Mungo and other degraded outsiders. Equiano was repeatedly dismissed and attacked with anonymous libels in the same newspapers he wrote for. The ‘African Humanity-mania’, spat a letter in the Public Advertiser, printed immediately below one of Equiano’s calls for abolition, was simply a novelty designed to sell papers to gullible fans. Even Equiano’s fellow abolitionists tended to present him as a ‘phenomenon’ to be gaped at, rather than as a skilled author in his own right. This treatment echoed the patronising reviews of the enslaved African-American poet Phillis Wheatley in 1773, who was marvelled at as ‘a prodigy in literature’ and a ‘literary phenomenon’, not, according to the Critical Review, because she had any more than ‘tolerable genius’ but because her writing at all was an oddity in a world where ‘the Negroes of Africa are generally treated as a dull, ignorant, and ignoble race of men, fit only to be slaves, and incapable of any considerable attainments in the liberal arts and sciences’.

Nevertheless, as Equiano was beginning to write his Interesting Narrative, an item in the Morning Chronicle (perhaps placed there by his publishers) reminded readers that ‘Gustavus Vassa’, an African living in London, had ‘distinguished himself by occasional essays in the different papers, which manifest a strong and sound understanding’. By 1792, ‘the celebrated Gustavus Vassa’ had toured Britain widely with his book and was ‘so well known in this kingdom’ that his wedding was reported in the papers and ‘an immense crowd of people’ gathered to attend. Even while his letter in the Morning Post satirised the excesses and exposures of celebrity culture, writing it was a way for Equiano to enter a new world of fame offering opportunities and objectification.

Celebrity treads a fine and unstable line: between admiration and intrusive curiosity, between being perceived as distinguished and being perceived as a ‘strange monster’. The new celebrity culture of the late 18th century provided ordinary Britons with an ever-changing cast of heroes, villains and clowns, who shaped new ideas about race and identity. It helped to make the nascent British Empire seem both a familiar part of everyday life and a distant playground for fantasy and sentimental pleasure. It also, sometimes, provided a means for the subjects of that Empire to answer back.

Ruth Scobie is the author of Celebrity Culture and the Myth of Oceania in Britain 1770-1823 (Boydell & Brewer, 2019).

The topics are thoroughly discussed, and everything is quite open and honest. There is no doubt that knowing the facts is beneficial. Is my website really lucrative in terms of sales? Please consider the following. trap the cat